The Wizard of Sweetens Cove

Wildly innovative, maverick golf course creator Rob Collins, C’97, leads a renaissance in course design by looking back to the history of the sport. And it all started with the world’s first “social media golf course.”

This fall, Rob Collins, C’97, will be celebrating two notable events in his career as a golf course designer. First, he’ll be breaking ground on a new course in Aiken, South Carolina, a project with all the hallmarks that have made his firm, King Collins, possibly the most innovative force in the golf world today. “The Hammer Course” at 21 Golf Club will feature quirky elements from the sport’s golden age in the early 20th century—wide undulating fairways, greens with unexpected contours, bunkers in surprising places, and so many intriguing choices for golfers that the holes will never play the same way twice. Golf Digest, which has referred to Collins’ courses as “genre-expanding risk/reward sensations,” recently described the Aiken project this way: “Collins ... needs little encouragement to construct audacious holes that haze the line between destruction and salvation. The Hammer promises more of the same, with Siren-like shots that will attempt to lure players into pursuing more than they can handle.” To top it all off, the course will have 21 holes rather than the standard 18. And those three extra holes will be “reversible,” meaning they can be played either way. Why have three extra “reversible” holes? Why not.

“I’ve always refused to travel a traditional path,” Collins says, a statement that describes both his approach to golf course design and to his life generally.

Which brings us to the other thing he will be toasting this fall, the 10th anniversary of the first course he and Tad King designed, Sweetens Cove, in South Pittsburg, Tennessee. The unlikely story of how Collins transformed a broken-down nine-hole course in the middle of nowhere, with no money, into what Golf Week has ranked as the 49th best modern course in the United States—and in the process lured Peyton Manning, Andy Roddick, and Jim Nantz to become co-owners—is a tale with more drama and surprises than the courses Collins now creates regularly. It has been described as Field of Dreams meets Tin Cup.

“Every course we’ve designed since then has flowed from Sweetens Cove and what we accomplished there,” he says. “That’s been our tree of life.”

"We wanted a level of quirk," Collins says about the Sweetens Cove design. "We wanted something fun and memorable." Photo by Rob Collins

"We wanted a level of quirk," Collins says about the Sweetens Cove design. "We wanted something fun and memorable." Photo by Rob Collins

There’s little in Collins’ early life to suggest he would become one of golf’s creative geniuses. His fairly conventional childhood on Signal Mountain outside Chattanooga involved playing almost every sport but golf—tennis, basketball, baseball, soccer. His father was a gastroenterologist, and his mother was a biology professor at UT Chattanooga, and occasionally they would play a round of golf with Rob and his older brother, Lewis, on family vacations.

When time came to pick a college, Collins followed the lead of his brother, who attended Williams College in Massachusetts. Visiting Lewis, Rob fell in love with the small college atmosphere, but he wanted to stay in the South, so he chose Sewanee. Collins admits his four years on campus were more social than scholarly and that he basically stumbled into his major, art history. Then again, the choice wasn’t completely random. His great-grandfather, Robert Wadsworth Grafton, was an accomplished artist who painted the presidential portraits of Calvin Coolidge and Herbert Hoover. “There was a genetic line that didn’t quite reach me,” he says. “I can’t paint, but I was comfortable studying art history. It wasn’t just the images but also the social and historical context I found really interesting.”

Despite his focus on friends and fun, Collins did come to appreciate something important during his Sewanee years: the value of critical thinking. The lectures of longtime Math Professor Mac Priestley in particular, in a class called Writing Calculus—designed to make high-level math accessible to liberal arts students—had an impact. “He pounded into us the value of a liberal arts education,” he says. “It teaches you to think critically, and that’s useful in any profession.”

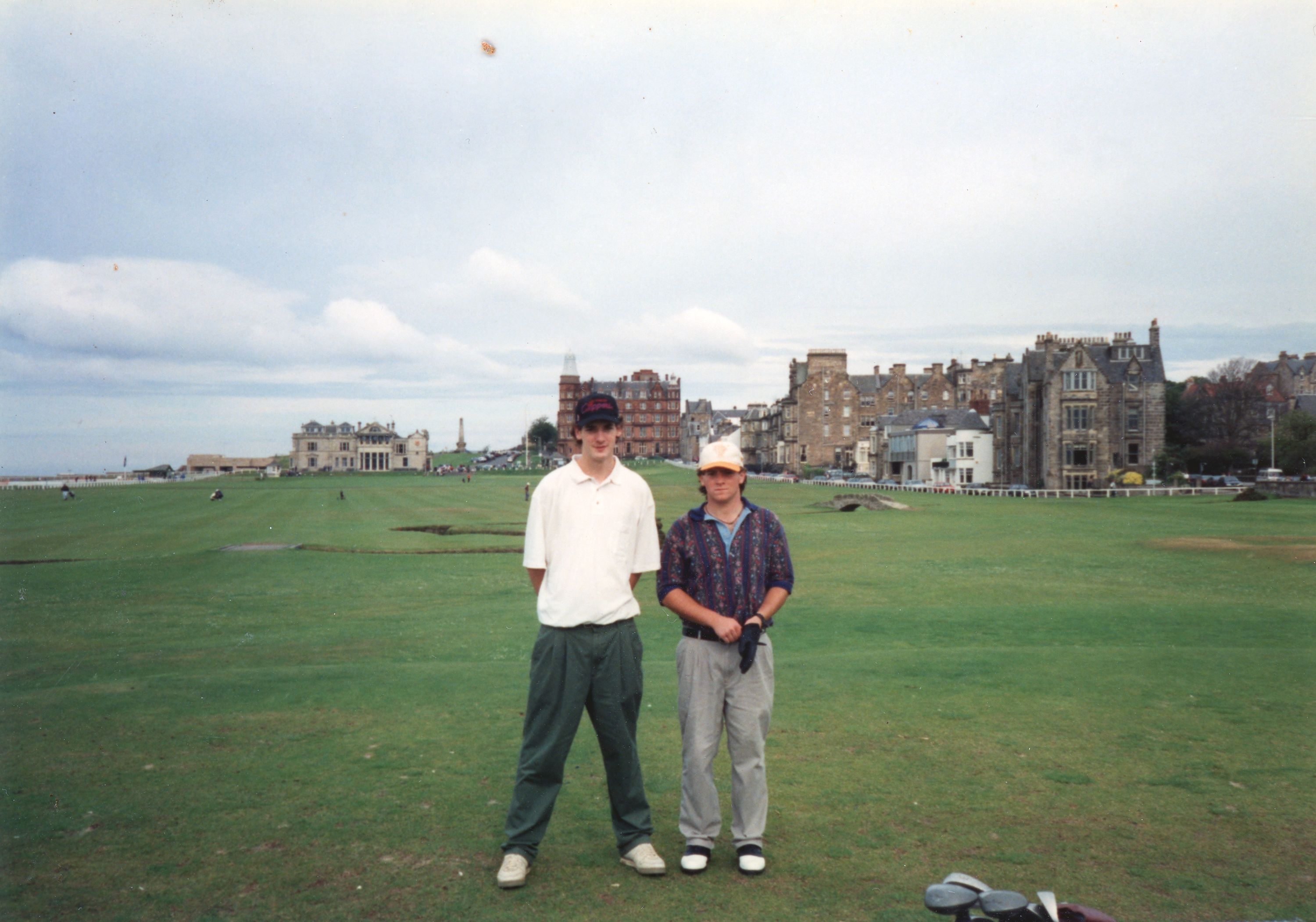

Critical thinking seems to have played a role during a golf trip to Scotland that Collins took with a friend during his sophomore year. He had begun playing more golf in his later teens, and the highlight of this trip was playing both the hallowed Old Course and the New Course at St. Andrews. Collins specifically remembers a shot someone hit where the ball landed and ran forever, a perfect shot beelining for the green, but at the last second it turned left on a little knob and plunked into a bunker. The guy tried four times to hit out but finally picked up his ball. Collins had never seen anything like that in America, where the landscape so affected play. Why is it, he wondered, that the American game is played in the air, whereas here at St. Andrews, the sport’s ancestral home, golf is played more on the ground? Negotiating unexpected terrain required more strategy, and Collins found it way more fun. “I came home wanting to be a golf course architect,” he says. “I thought it would be amazing to design these things.”

Collins (left) on the Old Course at St. Andrews, Scotland, during the trip that inspired him to become a golf course designer.

Collins (left) on the Old Course at St. Andrews, Scotland, during the trip that inspired him to become a golf course designer.

After graduating and spending six months in Europe with his girlfriend, Denise, the woman who would become his wife, Collins began to fret. “I have extremely low tolerance for doing things I’m not interested in,” he says. “I was so stressed in my early 20s because I loved my youth and freedom, and I feared I would never find my true passion in life.” He did find temporary refuge in a couple of fun sports-related internships, the first with the Chattanooga Lookouts, a minor league baseball team—where he mostly cooked hotdogs—and then with the NBA’s Atlanta Hawks. “I saw amazing stuff. Sometimes I had courtside seats. I saw Vince Carter dunk on Dikembe Mutombo 30 feet away.”

But then came soul-sucking jobs in advertising and real estate in Atlanta, and when Collins couldn’t take it anymore, he enrolled in the landscape architecture program at Mississippi State University, with a focus on golf course design. That degree led to an internship with a designer in North Carolina, followed by a job with former champion golfer Gary Player. It was 2005, and golf courses were being built like crazy in the United States, some 300 a year. Collins moved to Naples, Florida, to oversee the installation of a Player-designed course there. He quickly learned how problematic and inefficient golf course construction is, with tight-fisted middleman contractors often refusing to implement a designer’s vision. When Collins tried to work directly with a “shaper” (a bulldozer operator) on the project, a guy named Tad King, the contractor forbade King from speaking with him. Still, Collins and King became friends, and they talked about one day starting a design-build firm that would cut out contractors altogether.

Those dreams, and pretty much everything else, were dashed in 2008 with the global economic crisis. Golf course construction everywhere ground to a halt. Collins’ job vanished. He and his wife and daughter were forced to move in with his mother in Chattanooga. Collins scraped by on random landscaping gigs. “It was brutal,” he says.

Then, in 2010, Sewanee popped back into the picture. Acclaimed course designer Gil Hanse was redoing the University’s golf course, and Collins wanted to be involved. He reached out to Sewanee’s golf coach, the Rev. King Oehmig, T’77, who was overseeing the project. Oehmig was happy to connect Collins with Hanse, but he also knew of anther project half an hour away in South Pittsburg, a town of 3,000. There, another Sewanee grad, Bob Thomas Jr., C’64, principal owner of Sequatchie Concrete Service, also happened to own the local municipal golf course. Calling it a “golf course” was a stretch. It was basically a cow pasture with nine holes punched in it. Still, Collins (and King—they had formed their company) figured this was his one big chance. “We knew we wouldn’t get a second one if we screwed it up,” he says. “Thomas just wanted to touch it up. I wanted to build the best nine-hole golf course in the world. I told Bob, ‘If that’s what you want, hire us. If not, hire someone else.” Thomas hired him.

Philosophically, Collins felt that by the second half of the 20th century, golf course design had lost its way. Courses had become paint-by-numbers amenities for real estate interests. He wanted to create something more authentically rooted in concepts from Great Britain. He also admired the original design of Augusta National, home of the Masters, and Pinehurst No. 2, the iconic course in North Carolina that has hosted the U.S. Open. “These are courses that allow for shots along the ground, where contour can affect shots, where the shape of greens has an impact,” he says. “Sweetens was about putting all those things in a blender and spitting out something original. We wanted a level of quirk. We wanted something fun and memorable.”

From the start, there were challenges. Collins wanted his bunkers lined with wild, twisted grasses, which required planting by hand; but when the seeds never germinated, he had to do it all over again, two miles of bunker edges. The most shocking development came two years into the work, with the course nearly finished: Sequatchie Concrete announced it was no longer interested in the project. “They decided to return to their core business, which is concrete manufacturing,” Collins says. Sequatchie did offer him the option of managing the project himself under a lease, which he viewed as insane, since he had no money and no experience managing golf courses. But he also had no choice. “I took it out of pure desperation. It was a damn good course. I couldn’t live in a world where it didn’t exist.”

The public-access Landmand Golf Club in Homer, Nebraska, was Collins' first 18-hole course design. The club sold all of its tee times for 2024 within two hours of opening them for reservation. Photo by Jeffrey Bertch

The public-access Landmand Golf Club in Homer, Nebraska, was Collins' first 18-hole course design. The club sold all of its tee times for 2024 within two hours of opening them for reservation. Photo by Jeffrey Bertch

Collins dug into his savings to finish the course after a potential investor pulled out, but on the same day Sweetens Cove opened for play in October 2014, he ran out of money. He had to lay off his crew and superintendent. In the following months, the bank hounded him incessantly. Collins knew that if his maintenance equipment got repossessed, Sweetens was done.

But in the midst of this insanity, something positive was starting to happen. Golfers were learning about Sweetens through social media. Writers from a couple of influential golf sites played the course and raved about it. “We would have died an instant death without Twitter and Instagram,” Collins says. “Sweetens was the first social media golf course. Advertising is a form of lying, and we had no money to lie to people, to be anything less than organic. Sweetens had an authenticity you just can’t buy.” The course had no clubhouse, no food, no beverages, and no lodging. It even had no plumbing. There was a port-o-john and a pre-fab shed from Home Depot. That was it. And people loved it. When the course is that good, who needs a flush toilet?

Sweetens Cove was still completely broke the day in 2019 when Collins received a call out of the blue from a real estate developer in New York named Mark Rivers. Rivers and his partner, Skip Bronson, are the kinds of high flyers who know people. Rivers wanted to invest in Sweetens, and some of his friends did too, people like Tom Nolan, who once ran Ralph Lauren’s golf line, and Andy Roddick, the former tennis champion, and Peyton Manning, Tennessee’s favorite son. “I always had grand visions for Sweetens,” Collins says, “but there’s no way you could possibly ever predict something like that.”

The new ownership team saw little reason to change much about a course people were traveling from around the world to play. They built a pavilion, provided a food truck, and put in a putting green. They also added plumbing and proper bathrooms. Today it’s almost impossible to get on at Sweetens. Rather than tee times, the place sells 40 passes a day that are more like ski passes. Folks are encouraged to hang out all day and play as much as they want.

Collins continues to build new and intriguing courses across the country. He’s helping lead a renaissance in golf course design that’s injecting fun, mystery, and excitement back into the game. But Sweetens will always hold a special place for him. “Our original general manager, Patrick Boyd, remarked very early on that he felt Sweetens would be the epicenter of a new form of golf and a new way of thinking about golf,” Collins says. “His words seem to have been prophetic. The golf at Sweetens and the relaxed culture around the club is so different than anything else. It has become an important marker on the timeline of golf in the modern era.”