Stepping Up with Termaine Hicks

Wrongly accused and incarcerated as a young man, Termaine Hicks spent 19 years fighting for justice. Along the way he found invincible faith and, finally, freedom.

It is well known in the Episcopal Church and beyond: Education for Ministry (EfM) changes lives. Most of the more than 120,000 people who have participated in the four-year theological education program will agree. Many will have a tale of transformation to share.

Few will have a story as heart-wrenching as Termaine Hicks’s. Framed for rape in 2001 at the age of 26, Hicks was falsely incarcerated for nearly two decades. Upon entering prison, Hicks was forced to separate from his son, who was only five years old at the time of his sentencing.

Termaine Hicks, 47, on West Girard Avenue in West Philadelphia on Dec. 2, 2022. Hicks was convicted of weapons offences and rape of a woman in 2001 and served 19 years in prison for a crime he did not commit. He was exonerated in 2020. During his time in prison he joined the Education for Ministry (EfM) program, wrote plays, and later formed S.T.E.P.U.P. (Selfless Thinking Expresses Potential that Uplifts People). Hicks also produced videos on gun violence and bullying to help younger people avoid making mistakes that could affect them for the rest of their lives.

Termaine Hicks, 47, on West Girard Avenue in West Philadelphia on Dec. 2, 2022. Hicks was convicted of weapons offences and rape of a woman in 2001 and served 19 years in prison for a crime he did not commit. He was exonerated in 2020. During his time in prison he joined the Education for Ministry (EfM) program, wrote plays, and later formed S.T.E.P.U.P. (Selfless Thinking Expresses Potential that Uplifts People). Hicks also produced videos on gun violence and bullying to help younger people avoid making mistakes that could affect them for the rest of their lives.

Though EfM groups commonly gather in parish buildings, some convene in prisons. It was in such a group at the State Correctional Institution—Graterford, a maximum-security prison in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, that EfM group leader Ginny Slichter met Termaine Hicks for the first time.

Slichter describes her first visit to the prison. “Visitors walked directly through the general population to the other end of the prison where the chapel was, where the classes are held. You went with an armed guard, but it’s still pretty darn intimidating, this long walk to an ugly little room.”

“There were 12 men in the room, and they all stood when I walked in. They greeted me with such unexpected affection. I was replacing my beloved EfM predecessor, Dennis Warner, who had died recently of a brain tumor in the prime of his life. We were all mourning. The men told me how much they loved Dennis.”

Slichter said to them, “I don’t know how you feel about having a woman for a mentor. I don’t know how you feel about having a white woman.” One of the inmates replied, “Miss Ginny, everybody needs a mama!” For the first couple of years, she was known as Mama Ginny.

During that time, in the fall of 2008, Hicks joined the EfM group. “We don’t ask the men what they’re in for,” Slichter says. “Sometimes it comes out in the spiritual autobiography, but we don’t ask. As one of the men said, referencing the work of famed public interest lawyer and equal justice activist Bryan Stevenson, ‘Would you want to be known for the worst thing you ever did, for the rest of your life?’”

Termaine Hicks, left, visits with his youngest brother, Tyron McClendon, 38, as the two walk along Euclid Avenue in the Strawberry Mansion section of West Philadelphia where Tyron lives.

Termaine Hicks, left, visits with his youngest brother, Tyron McClendon, 38, as the two walk along Euclid Avenue in the Strawberry Mansion section of West Philadelphia where Tyron lives.

The world now knows what Hicks did and did not do. On a November morning in 2001, Hicks had just walked his little brother, Tyron, to the bus stop in their south Philadelphia neighborhood, when he was called to be a real-life Good Samaritan. Hearing a scream pierce the darkness, he ran toward Dunkin Donuts and Saint Agnes Hospital. He saw two men running away from a figure on the ground near a dumpster.

Like the traveler in the Parable of the Good Samaritan, the victim had been left beaten, bloody, and half naked. When Hicks nudged her, she did not move. As he reached for his cell phone to call 911, two police officers ran to the scene. Three shots rang out, striking Hicks in the arm, chest, back, and buttock.

“I survived,” he says, “and I understood the gravity of the situation right away.” Officer Martin Vinson claimed to have witnessed Hicks raping the victim. He said Hicks had pulled a gun on police, but put it back in his pocket after being shot three times. The gun that was entered into evidence was registered to a Philadelphia police officer. All three shots struck Hicks from behind, yet Vinson said he was forced to fire because Hicks was lunging at him. During the trial a year later, the medical examiner would say he could not determine the direction from which the bullets that struck Hicks were fired.

Video footage showing the actual assailant dragging the woman into seclusion was never shown to jurors and soon disappeared from evidence. Hicks was convicted of rape and weapons offences, with 20 officers testifying against him. In 2003, he was sentenced to 12 1⁄2 to 25 years in prison.

Termaine Hicks in West Philadelphia on Dec. 2, 2022

Termaine Hicks in West Philadelphia on Dec. 2, 2022

Immediately, Hicks appealed. He also reached out to the Innocence Project. In 2003, the Innocence Project had just 15 attorneys and could not take his case. In fact, it would be eight years before they could look at it.

During that time, Hicks worked his way through the local trial court, the appellate, and the Pennsylvania Supreme Court, until he only had one option remaining: the U.S. Supreme Court. “Twenty-seven judges had looked at my case by then,” explains Hicks. The U.S. Supreme Court hears fewer than 1 percent of criminal cases that it is asked to review. “Even the most seasoned attorney does not likely get the opportunity to go before them,” says Hicks, who was by this time arguing his own case pro se. “Attempting to reach the Supreme Court as a pro se litigant, would have been an exercise in futility so I withdrew my appellate rights. That means it’s over; you’re going to serve your sentence.”

Hicks was not eligible for parole because he maintained his innocence and would not express remorse for a crime he did not commit. It was 2012 by the time Hicks withdrew his appellate rights, which meant he would have another 13 years to serve.

Within 30 days of surrendering his appellate rights, Hicks was contacted by the Innocence Project. It was ready to take his case. The timing was uncanny. Hicks calls the Innocence Project team “relentless, God-sent, true advocates.” Still, it would take nearly another decade to set Hicks free. First, they had to show new evidence in order to ask for a new trial. Hicks says, “In the judicial system, there’s something called finality that is very hard to overcome.”

In this case, the new evidence came from Hicks’s clothing and his own body. The Innocence Project recruited high-profile forensic pathologist Michael Baden to determine the direction from which the bullets were fired at Hicks. Baden testified that all shots were fired from behind Hicks, so he could not have been lunging at the officer who pulled the trigger. The chief medical examiner recanted his prior testimony. The trial judge retired and was replaced by another judge, “which really set the ball in motion,” explains Hicks.

Then the pandemic hit. “Everything slowed down,” says Hicks. “It was brutal for the guys in the penitentiary. Inmates were sick, some were dying. There were weeks we never once left our cells. Then they began to let us out again—but only for 15 minutes a day. So, I could see the sun, or take a shower, or have a phone call—but only one. It was hard to maintain sanity.”

Twice a month, his attorney, Vanessa Potkin, would call from the Innocence Project. She would always say, “I’ve got some good news and some not-so-good news.” The good news was that he still had a chance, and the not-so-good news was another continuance—60 days, 90 days, 180 days. But on December 16, 2020, all the news was good. The conviction was vacated, and the charge dismissed. Termaine Hicks had been exonerated.

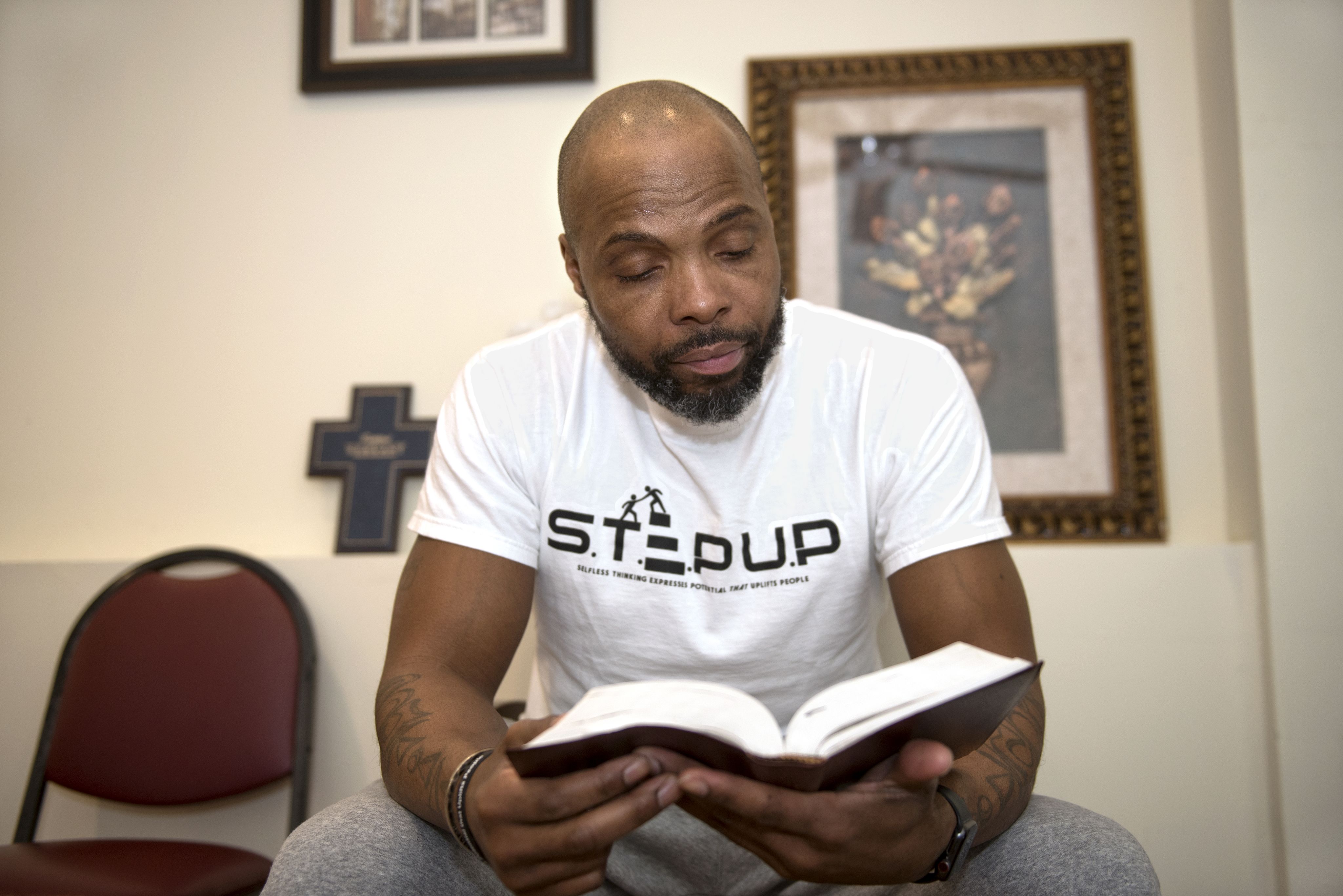

Hicks looks over scripture.

Hicks looks over scripture.

Through all the years of trials and incarceration, Hicks never lost faith. He says EfM provided him with a firm foundation so that, like John the Baptist, he would not be a reed shaken by every wind. He learned a lot about working with people, interpreting the Bible, and communicating faith. “You can’t be in this box when it comes to God and religion,” he says. “EfM taught me how to open the box, and also how to be diplomatic.”

He says, “EfM was a vessel. It was a chance for me to try to find out how God operates with us. I was already a devoted Christian, reading my Bible daily. I was writing Christian plays, engaged in independent study, and searching Scripture. Then I was invited to EfM by an usher in the church. He said ‘come sit, check it out.’” Hicks went to one session as a guest and was intrigued by the concept. “I liked how it was staggered, year one through four,” he says. “I liked interacting with all of it. I signed on to start the next year.”

During his 19 years in prison, Hicks noticed how new inmates entering into the penitentiary were younger and younger. Most of these kids had made a single mistake, he says, often as the result of bullying, and their entire lives were disrupted. Wanting to reach young people before fateful decisions are made, he began to produce videos on gun violence and bullying.

Seeing so many inmates broken by the prison system, Hicks determined he would find his strength in God. “Along the way I found a hidden talent,” he says. “I found what was already there.” He created an organization called S.T.E.P.U.P., an acronym for Selfless Thinking Expresses Potential that Uplifts People, and began writing educational scripts that were later turned into films.

One of those plays, Soldiers in the Army of the Lord, was performed at Graterford in 2012 in honor of Hicks’s EfM graduation. Hicks recruited other prisoners to act in the production. Slichter invited the Rt. Rev. Daniel G.P. Gutiérrez, the Bishop of the Episcopal Diocese of Pennsylvania, and other visitors from outside the prison to the performance. “We must have had 150 people in the audience, both inmates and guests,” remembers Slichter.

“I’m a playwright,” Hicks says. “In prison, I had to coax some of those guys up there. They had stage fright. My motto was, I’m not going to ask you to do something I would not do. Step up to it!”

Termaine Hicks, foreground, visits his youngest brother, Tyron McClendon.

Termaine Hicks, foreground, visits his youngest brother, Tyron McClendon.

Today Hicks serves alongside Slichter on the board for the Dennis H. Warner Memorial Foundation, which provides EfM scholarships for inmates and assists family members of the incarcerated. He often speaks for the Innocence Project. Prior to our interview, he had just given a talk for the Dutch Consulate at the United Nations in New York City. Hicks has a powerful testimony against corruption in policing and the judicial system, but his heart is formed by mercy as much as the call to justice.

After his dramatic exoneration and release from prison, Hicks spent six months just trying to ease back into society. Then he pulled out the S.T.E.P.U.P. scripts he had written while incarcerated. He thought about those younger and younger inmates, and knew he needed to get his message to young people before their first encounters with the judicial system.

Hicks speaks with his nephews. Pictured at left is Tyshir Purdy-Hicks, 16, and Sayree Washington, 16.

Hicks speaks with his nephews. Pictured at left is Tyshir Purdy-Hicks, 16, and Sayree Washington, 16.

“What we are doing is just reintroducing simple life decision-making,” Hicks explains. “The vision is to have these videos in every classroom.” He turned S.T.E.P.U.P. into a 501(c)(3) non-profit organization to produce and promote the videos, which are now being requested in schools around the nation. S.T.E.P.U.P. also offers motivational speaking and training in schools, teaching positive decision-making, how to recognize bullying, and how to communicate with peers who carry guns, sell drugs, or who drink and drive. The training also emphasizes the importance of physical fitness and a healthy lifestyle. “We empower youth to use their voice to prevent bullying and violence,” says Hicks about his presentations at schools.

“This is my ministry,” he says. “EfM gave me the skills, and this is my gift back to the world. I could have just disappeared, but I want to be on the front lines. God saw fit to keep me alive. I could have been paralyzed; there are still fragments of that bullet near my spine. As the Psalmist wrote, ‘God knows our frame and remembers we are made from dust.’” With that understanding, I am able to move forward. Bitterness is cancerous, and this knowledge frees up my mental space: I know God had me. I chose life, because my Father God allowed me to live and continue to grow.”

Get Involved

Bring S.T.E.P.U.P. training to your local schools. Read more here.

Subscribe to stepup4youth.org on YouTube. By subscribing, you can bring S.T.E.P.U.P. closer to its goal of 1,000 subscribers, a milestone that will increase the organization’s visibility.

Donate here to help us reach more people with EfM.

Hear Termaine Hicks Speak in Sewanee, Tennessee

Termaine Hicks is the keynote speaker at the 2023 Education for Ministry Conference, sponsored by the School of Theology at the University of the South. Hicks’s keynote speech will take place on June 21, 2023, at 7:00 p.m. CDT. The presentation is free and open to the public and will be livestreamed for those who cannot attend in person. Please watch School of Theology social media and publications for more information about the event and for the livestream link.

Interested in Education for Ministry?

To find an EfM group near you or learn more about EfM groups in prisons, read more here.