Reparations: More Than Money

An Interview with Bishop Eugene Sutton

1584: Richard Hakluyt the Elder, an English backer of the colonization of Virginia, proposes the planned colony be supplied with laborers and craftsmen from Eastern Europe: “Men skillful in burning of soap ashes, and in making of pitch, and tar, and rosin, to be fetched out of Prussia and Poland, which are thence to be had for small wages, being there in manner of slaves.”

October 1, 1608: The first of these workers arrive at Jamestown. The colony was almost 18 months old, but it had already experienced warfare with the Native Americans, the exhaustion of local food sources, saltwater poisoning from drinking from the brackish river, and outbreaks of malaria, fevers, and dysentery.

At the colonial outset of this nation, slavery was not a foregone conclusion. Virginia’s earliest settlers were from privileged backgrounds, the second, third and fourth sons of prosperous Britons. They were adventurers and fortune-hunters with plans to make a colony, make money, and make an English church on the shores of America.

While they brought with them some of their own servants, it must have been apparent immediately that their survival would depend on more labor: the cheaper, the better. The mineral resources of the colony disappointed the colonists and their investors. They had shipped back to England little more than a ship full of fool’s gold. But as they considered the vast forest that surrounded them north, south, and west, the colonists must have remembered that idea of Hakluyt’s. Given that there were shortages of almost everything but wood fuel, it is no wonder that on only the second supply ship from the metropolis were a handful of Eastern European craftsmen, the very people suggested by Hakluyt for making the North American forest economically productive.

1619, summer: Conditions would have been hot, humid, diseased. The first colonial government is being elected, but the Englishmen withhold voting rights from the Eastern Europeans. On June 30, the Poles, Slovaks, and other ethnic minorities strike, unwilling to work in a society in which they cannot vote. A month later, the General Assembly meets for the first time. On July 21, the strikers and their countrymen are granted full voting rights. In time they vote, run for office, and hold property.

1619, that same summer, only a few weeks later: The first enslaved Africans set foot in Anglo-America, only about 120 miles south of the modern city of Washington.

It was on that spot that the Rt. Rev. Eugene Sutton of the Episcopal Diocese of Maryland gathered with other faith leaders on July 13, 2021, to encourage Congress to pass House Resolution 40. I interviewed him that afternoon. He was still enthusiastic from the morning’s events.

“HR40 calls for the establishment of a blue-ribbon bipartisan commission to look at, study, consider, and dialogue about reparations. The disappointing thing—though not surprising to me—are the legislators from Congress who don’t even want to discuss it or research it. Information, apparently, is dangerous.”

Sutton was there to speak to the issue from a theological and biblical perspective, and particularly to speak of the Diocese of Maryland’s experience in the reparations debate. “The Diocese first supported the principle of reparations in my pastoral letter of May 2019.”

“Reparations,” Sutton had written, “at its base means to repair that which has been broken. It is not just about monetary compensation. An act of reparation is the attempt to make whole again, and/or to restore; to offer atonement; to make amends; to reconcile for a wrong or injury. Isn’t that our work in this broken world?”

A rhetorical question like Sutton’s operates on the assumption that those it addresses will come to widespread agreement—that yes, unequivocally, reparations for slavery is the right thing for Episcopalians to do. But The Episcopal Church descends in large part from that English church planted on the shores of Virginia, and Sutton descends from Africans who were enslaved in the society it sought to sanctify. He does not back away from naming the harm that was done.

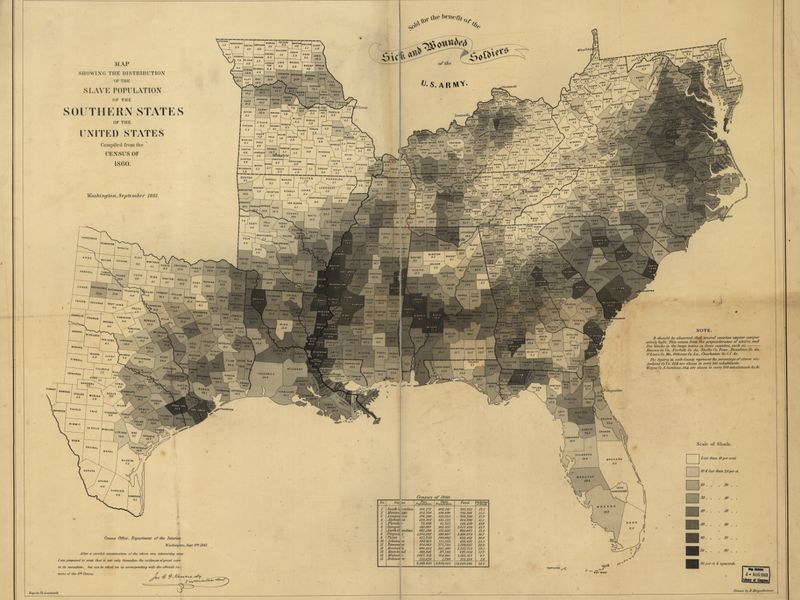

“Thievery—theft. We stole, The Episcopal Church stole, banks stole, governments stole. We stole from Black people, and we never paid it back. I learned in Sunday school a long time ago that if you steal something from somebody, you pay it back or you make restitution, or you have no real hope of reconciliation. You can be nice, you can have smiles, you can say, ‘Oh, I have Black friends,’ but there’s still an elephant in the room: you stole from my ancestors, and no wealth was passed down. You achieved wealth, and we did not.”

The Rt. Rev. Eugene Sutton of the Episcopal Diocese of Maryland

The Rt. Rev. Eugene Sutton of the Episcopal Diocese of Maryland

1640, summer: In previous years, Jamestown colonists had used the word “servant” to describe workers of both European and African descent. It is unclear what the lives of these servants looked like exactly, whether they were relatively emancipated, whether their time of service was temporary or permanent. But now one such servant, a Black man named John Punch, escaped with two European servants—a Scotsman and a Pole—to Maryland. They were caught, returned to their master, and prosecuted in court on July 9. The two white servants received four more years of indenture under the same harsh master. Punch received a life sentence. Punch became the first documented Black slave in Anglo-America.

January 1, 1863: Punch’s enslaved descendants are declared free, effective according to the Emancipation Proclamation at the stroke of midnight and the beginning of the new year.

But the slaveholder’s rebellion continued for another two years. During the chaos of the Civil War, some enslaved people made their own way to freedom, or were freed by Union armies as they won control of the south, or were freed by circumstance: masters killed in battle or lost, mistresses fleeing plantations. Some freed themselves in small rebellions of their own making.

Union General Oliver Otis Howard was known during the War as “the Christian General” for his piety. Eventually he would be known as a founder and namesake of Howard University and a leader in the effort to Reconstruct the slave states as free, multi-racial democracies. He had lost his right arm in the Battle of Fair Oaks in June 1862.

July 28, 1865: Howard issues Circular #13, a post-War federal order that effectively established a policy of redistributing plantation lands to be owned by the Black people who had worked them as slaves. He must have signed it left-handed.

The debate about reparations goes back at least that far. One early proposal that took hold in the popular imagination, if not in reality, was “40 acres and a mule.” Newly freed Black families would own their own land and the means of getting their produce to market. While white abolitionists mobilized to raise funds for schools, colleges, churches, and other civic institutions, new Black-majority electorates across the South voted in new state governments that finally represented their populations. In 1868, a majority-Black convention established a new constitution for South Carolina: it based representation on population rather than wealth, abolished debtors’ prisons, expanded rights for women (though not the vote), created an integrated and free public education system, and ended the prohibition of interracial marriage. The document was put directly to the entire state population for approval and subsequently ratified by the United States Congress.

Reconstruction represented a multiracial effort to redeem the South from slavery and to make restitution to those who had suffered. There were concrete plans to improve life, educate, and build wealth in Black communities, plans that continue to inspire reparations advocates today.

Sutton and the diocese have taken their own concrete steps since his pastoral letter’s release. “A little over a year later, we voted on the money: a $1M seed fund to invest in the impoverished Black community. After 300+ years of The Episcopal Church colluding with everyone else in taking wealth out of the Black community—first through slavery, then through Jim Crow, redlining—we decided to do something about that, to use Episcopal resources to invest in the impoverished Black community. We call that reparations, and I don’t know why people get upset about that.”

“We asked ourselves, how can we invest in the poor Black community?” Some in the reparations movement today have called for direct payments to the descendants of slaves. A handful of American institutions, including the Virginia Theological Seminary, have implemented their own versions of the approach.

Sutton states clearly the financial urgency of reparations: “Reparations is about more than money—it’s about education, attitudes—but it’s not less than money. Money was stolen from the Black community for centuries.” Restitution, he continued, “can’t be done on the cheap. If it doesn’t cost you anything, there’s no repair.”

It isn’t as simple, however, as a direct transfer of cash. Sutton believed it was important to use what he called a “moral formula,” rather than a mathematical one, to figure out the diocese’s response. “We’ve determined that checks to individuals do not make as much of an impact on the community, but if we can leverage the money we have, we can get others to invest as well. Rather than giving someone fish, we are giving them the tools to fish for life. That’s what reparations means to us: more than money, but not less than money.”

One of the diocese’s first decisions was deciding on an amount. “$1 million represents about 20% of our annual budget. We can’t possibly repay all that was gained, but we wanted it to be enough to cost us something. That amount means we can’t fund some other things, but what’s more important than repaying a debt?”

“We also wanted it to be large enough to make an impact for the impoverished Black community. That million dollars is a seed fund taken from diocesan resources. Informally, without a major campaign, we asked congregations and individuals to pay into it as well. We collected another $125k just from that. We set up a task force—made up of different geographical parts of the diocese, interracial, intergenerational, rich and poor—looking at how to invest in these five areas: education, environmental degradation, healthcare, housing, and microeconomic activity, and job creation.”

The diocese will support new and existing programs in those five areas, but they state clearly that such funds are not grants. “Don’t thank us for it. It comes with ‘We’re sorry.’ This is a debt we owe you. This isn’t charity—this is justice.”

One notable program was named in honor of the bishop, the Sutton Scholars Program. In partnership with the Baltimore public schools, the Baltimore Ravens Foundation, and other groups, one hundred Black high school students are taught “life skills, study habits, time management, money management. We give them a stipend and help them set up bank accounts.”

“They work hard, they’re motivated, they’re bright and energetic. Some of them live in terrible neighborhoods or attend substandard schools where everything is against them. No matter what they do, they will never end up at a University of the South, or an Amherst College, or an Ivy League school. They will never get there, and it’s not their fault. It is generations of societal neglect and oppression and racism. They happen to be born in the wrong zip codes, and they happen—like me—to have beautiful, Black skin.”

“Why are we doing it? Because we believe in God. And God believes in them, when society wants to turn their back on them.”

Reparations cannot just be a transfer of money from white people to Black people, repeated Sutton. “That’s ridiculous, that’s unworkable. Reparations—to people of faith—is what this generation can do to repair the damage of previous generations. We didn’t cause the mess that we’ve all inherited. We’re all in it, whether your ancestors came over on the Mayflower or a slave ship. We’re all on the same boat now. We can’t all do everything, but all of us can do something.”

September 12, 1865: Just shy of the third anniversary of the writing of the Emancipation Proclamation, the new President Andrew Johnson countermands Circular #13 by writing and issuing Circular #15. A plantation owner from Johnson’s home state of Tennessee had complained, and other southern whites were stoking fears of an impending race war. Johnson’s new order hamstrings land redistribution. White landownership is restored. Black people are encouraged to earn wages rather than seek property. New laws are quickly passed in southern states, some of which prevent Black people from owning or leasing land at all. The tone is set for rolling back Reconstruction.

1877: The results of the previous November elections remain contested. A divided Congress repeatedly fails to come to consensus about who has been elected president, Republican Rutherford Hayes or Democrat Samuel Tilden. Ultimately, a compromise solution is devised: Hayes will become President, but all federal soldiers will be withdrawn from southern states. Some of them were perhaps moved immediately to Washington, where inauguration security was being heightened in the face of threats of armed violence from white supremacist militia groups. The inauguration takes place in peace, but Black-led state governments and other institutions in the South are left totally without protection. The Klan and other groups carry out a terroristic spree against Black leaders and the general populace. Reconstruction is ended.

Even piecemeal progress is met with resistance. Although Sutton’s project has found a broad base of support within the Diocese, it has not been free from challenges."

The biggest challenge was “education—getting people to even want to think about it and talk about it. There was strong resistance to that. There still is to this day. That’s what’s behind some of the pushes against what professors can teach in their classrooms.”

Sutton calls it “a fear of history. If you don’t want the full history to be told, that’s a problem. But the Diocese of Maryland had spent years in anti-racism training, in getting people’s minds around what The Episcopal Church’s participation was in those systems of racism and injustice and oppression.”

It surprised Sutton where much of the resistance to the proposal came from. “Some would expect there would be more resistance among lower- to middle-income white communities. But I’ve gotten more checks from poor and low-income white congregations than from upper-middle-class white congregations. Here’s the thing: most of the resistance is among the well-heeled. Most resistance is from the rich. We can speculate why, but I think it goes back to what Jesus said a long time ago, perhaps tongue in cheek, perhaps with a smile on his face: it’s easier for a camel to pass through the eye of a needle than for a rich person to enter the kingdom of heaven.”

But 2021 is not the 19th- or even the 20th- century, and Sutton has found support across all the dividing demographic lines of the diocese.

“We have so many well-to-do and rich friends, faithful Christians, who know that all that they have was not just the product of their own toil. They know—if they’re honest—they know that they were privileged to either go to this good school or have these connections. They are anxious to ask, ‘How can I help others achieve what I have? I had certain advantages that millions and millions of especially Black persons—descendants of slaves—they never had those opportunities.’”

In his letter, Sutton had called on the diocese to become a “living epistle to the whole Church.” He also stated that the Church’s discussion of reparations would and must be distinct from the political arena. “For us, ‘repairing the breach’ is not a mandate from a government or leader, but a mandate from our God to commit to the rebuilding of a relationship between the world and God, between individuals and communities and to seek a better world for our children.”

It is this theological and biblical foundation that dominates Sutton’s appeal to the Church and the nation, but it was his experience being a bishop that motivated him to take up the banner of reparations.

“I didn’t really start talking about reparations until about 10 years ago, after I became bishop. It wasn’t that I was against it before. But guess what? I wasn’t educated on it. I was just doing my work as a pastor and priest. But when you become a bishop, you begin to see things more systemically. One of the vocations of the bishop is oversight. What you begin to see are the patterns. And the older I get—I’m a happy guy, I have friends of every creed and color—but the older I get, the more I get angry at the failure of the Church. I saw that more and more as a bishop, and how our diocese has failed the African-American community.”

But Sutton hasn’t been alone. “My diocese has helped me too. The Diocese of Maryland—for at least the last 15 years—has been studying this issue. So when I became bishop, I got on the bandwagon of what had already been started. Sometimes these things take a long time, but now the moment is ripe.”

At one such moment, Sutton had hesitated. In 2017 there were more discussions in the diocese about a potential reparations resolution to be taken up at their convention. It was at a clergy group meeting that one priest approached Sutton to ask directly what he thought.

“I’m for it,” said Sutton. “The priest said, ‘Well, Bishop, if you’re for it, you’ve got to tell people. You have to let us know why you’re for it, and if you want it to happen, get out there and sell it.’ Once again, at my advanced age, that priest taught me a lesson about leadership.”

“My advice to other bishops, deans, rectors: you’re going to have to show some backbone on this. But in most cases—90% of cases—people will follow you on this if you make the case—if you make the case! If you’re wishy-washy, if you’re uneducated, the people will follow whatever news source or community talk they hear, and it may have no basis in fact.”

It seems fair to say that Sutton has undergone a conviction of the spirit over the course of his leadership of the diocese. “I can’t live with the fact that I am the head of an institution that acquired wealth from oppression and never really paid it back. I don’t want to go to heaven like that, unless I can say I tried to correct that. I hope we can say in the Diocese of Maryland that we’re still sorry, but by the grace of God we did something.”

1946: Under the Claims Commission Act, Congress establishes a pathway for Native Americans to pursue claims against the U.S. government.

1952: West Germany begins paying reparations to the Jews of the new nation of Israel.

1980s: Congress establishes a commission to examine the history of the internment of Japanese-Americans in prison camps during World War II. In 1988, Congress pays out $1.6 billion to survivors.

August 2021: The House of Representatives recesses without taking up HR40 for debate.

Now: What will we do?

Bishop Sutton will speak to the Sewanee community as part of this year’s Alumni Lectures. He intends to address concrete things churches and institutions can do. Ultimately, he intends to pose a challenge. “Far too often, the Church is behind the curve on so many issues. Others lead on the issues of justice—the right thing to do—and then the Church eventually comes along.”

“We are humble enough to say that our feeble efforts in and of themselves will do nothing. But with the Holy Spirit, we’re going to make a huge difference. If we can just catch up to the Spirit, we might be able to do something. Let this be one issue where the Church leads. Let the Church lead in America.”