Reimagining the Road Ahead:

Creation Care for the Future

As the world moves towards a new normal on the heels of a global pandemic, many of us are struggling with compassion fatigue. Our ability to care about issues beyond our own lives has been sorely tested by the coronavirus, and feelings of isolation and disconnection make it difficult to imagine that we will ever again meaningfully engage with the goals we once pursued. Yet in this upending of “business as usual” lies a unique opportunity, says the Rev. Sven vanBaars, rector of Abingdon Episcopal Church in White Marsh, Virginia.

The grounds of Abingdon Episcopal in White Marsh, VA. The land was a gift from George Washington’s maternal grandparents.

The grounds of Abingdon Episcopal in White Marsh, VA. The land was a gift from George Washington’s maternal grandparents.

“The pandemic has raised a lot of questions,” he says, “as well as given us the time and space to reflect and reimagine the future. For instance, do we really need bricks and mortar to be a church? If the answer is no, then what would parish life look like? What could it look like?” There is a great benefit to having the opportunity to re-evaluate what is really important to us, vanBaars says. “I had a mentor years ago who told me, ‘Never underestimate the power of Maundy Thursday when it comes to getting rid of things you just don't want anymore,” he says, laughing. “The pandemic has done a lot more than just give us time to strip the altar. It’s provided a huge opportunity to think about what we don’t want, and what we do want, for the future.”

Sven vanBaars blesses the animals of Abingdon Episcopal in White Marsh, VA.

Sven vanBaars blesses the animals of Abingdon Episcopal in White Marsh, VA.

For Abingdon Episcopal, that thinking has included reconsidering how the parish’s land is used, as well as its physical structures. The church sits on a parcel that was a gift from George Washington’s maternal grandparents, but there is additional land, nearly one hundred acres of it, that was purchased by the church about 30 years ago and has been growing timber ever since. Hearing Brian Sellers-Petersen, Missioner for Agrarian Ministry for the Diocese of Olympia, speak at Virginia’s diocesan convention in 2019 led vanBaars to begin reconsidering how Abingdon might use its assets. “We have this timber farm,” vanBaars says, “but after hearing Brian speak, we began to actively wonder, ‘What else can this land produce? How else might we use this land in a way that is consistent with our values?’”

Currently, Abingdon is evaluating several possible paths. One involves converting the land to a solar farm, and another would create a school for young people on the neurological spectrum. While solar farms are increasingly popular on the eastern edge of Virginia where Abingdon Episcopal is found, the idea for the specialized school emerged from a discussion with a parishioner who lives in nearby Williamsburg. “There is a gap after high school graduation for young men and women with neurological differences,” vanBaars explains, “because public school doesn’t include vocational training and college isn’t a viable option. What if we established a farm-based school, a hybrid approach to learning that combined vocational training and therapeutic care?”

Parishioners of Abingdon Episcopal use tarps to visualize where solar panels might go.

Parishioners of Abingdon Episcopal use tarps to visualize where solar panels might go.

In reimagining how the church might use their assets as part of their commitment to creation care, Abingdon worked with a parishioner who is a professor of wetlands ecology at Christopher Newport University to evaluate the impact of a solar farm on wildlife, as well as the church's carbon offsets and carbon footprint. “We try to model good community discussions, about creation care and everything else,” vanBaars says, “but the disruption of the pandemic gave us time to really dig in and understand how our decisions would impact our surroundings.”

Modeling discussions around creation care has been an initiative of The Episcopal Church for several years, and at General Convention in 2018, a task force was established to provide grants and guides for parishes wanting to participate in those conversations and the efforts that result from them. In establishing the task force, the Church identified three core components of creation care: liberating advocacy, life-giving conservations, and loving formation. Several parishes across the country made the Presiding Bishop’s call to action a priority, fostering educational conversations, building community gardens and beehives, and launching sustainability initiatives.

“Remember, this is God's world.” —Presiding Bishop Michael Curry

But that was before the pandemic turned parish life upside down.

Given the unprecedented disruptions of the past year, is it really that important for Episcopal churches to focus on creation care now?

As it turns out, the answer is a resounding Yes.

The Devastating Effects of Climate Change

Climate change, of course, has been a hot-button political issue in the past decade, but pushing political agendas aside, one only needs to scroll through a list of weather-related events in recent years to recognize that we have a problem, and these disasters have escalating price tags.

According to Climate Central, an independent source for climate change information, this is to be expected, since the effects of climate change occur in "messy jumbles." These messy jumbles mean that a single climate event has multiple effects, and the effects have a compounding impact. Read more about the compounding effects of climate change at:

A 2019 post on State of the Planet, a blog produced by Columbia University's Earth Institute delineated the effects of climate change most likely to affect "every American's way of life."

They include increased utility bills, higher homeowners' insurance rates, increased taxes to fund infrastructure repairs, a rise in allergies, an increase in mosquito-borne diseases, increased water contamination from storms, higher food costs and lowered food variety, greater food insecurity for impoverished areas, decreased ability to endure outdoor labor or enjoy outdoor exercise, and disruptions to aviation brought on by excessive heat and the fact that hotter, less dense air impedes an airplane's ability to travel fully-loaded with passengers and luggage.

If those are not reason enough to care, there is always the possibility of even greater, irreversible losses. In a September 2020 article of Yale Environment 360, published by the Yale School of the Environment, Mario Alejandro Ariza, author of the book, Disposable City: Miami’s Future on the Shores of Climate Catastrophe, noted that a sea level rise of only six inches would threaten the drainage system of the city of Miami; the drainage system that, in essence, keeps Miami from returning to the swamp it once was. Six inches of sea level rise may sound like a distant threat, but only until you realize that since 1993, the sea water has already risen five inches. Much of that is due to a phenomenon called “sunny day floods,” leading many scientists to predict a six-inch water rise by 2030, and a six-foot rise by 2100.

Over on the West Coast, the outlook is equally grim. The LATimes reported in 2019 that the current rate of erosion to the coastline will necessitate several costly measures, such as seawalls and forced relocations. “More than $150 billion in property could be at risk of flooding by 2100—the economic damage far more devastating than the state’s worst earthquakes and wildfires,” Rosanna Xia writes. “It’s not too late for Californians to lead the way and plan ahead for sea level rise, experts say, if only there is the will to accept the bigger picture.”

The same, of course, is true for all 95,000 miles of coastline in the United States. Protecting the shoreline, and coastal cities, will require massive efforts and billions of dollars. Add in a few droughts in the Midwest, hurricanes in the Outer Banks, blizzards in the Northeast, and mudslides in the Pacific Northwest, and we are looking at a cost of $1.9 trillion annually by 2100 to simply maintain what we already have, according to the National Resources Defense Council.

www.nrdc.org/sites/default/files/cost.pdf

Social Justice and Climate Change

The potential impact of climate change is enormous, and what’s more, research has shown that it is the people least able to afford it who will be most affected by catastrophic weather events and extreme temperatures. It might be easy, for instance, to look at the waterfront high-rises and yacht-filled marinas of Miami and imagine that only the wealthy will be inconvenienced by the intrusion of saltwater, but the truth, Mario Ariza writes, is far different. “The City of Miami has a relative rate of inequality similar to that of developing countries like Paraguay and Colombia. Forty percent of the households in Miami-Dade County—of which the City of Miami is part—are working poor, with little savings and few assets. Nearly one-fifth live below the poverty line.” This means that the vast majority of the disruption caused by rising sea levels will fall on lower-income communities and people of color, the very people who can least afford to be displaced or install costly fixes.

This disproportionate impact can be seen in several other quality-of-life measurements, too, including personal health. A recent article about heart attacks in Discover magazine states, “There are disparities in risk based on where we live, our gender, and our racial and ethnic background. ... Part of what ups these risks is air pollution and socioeconomic factors. Researchers have even found that ZIP codes are one of the best predictors for heart attack survival—a critical finding for minority and underserved communities.”

In the same issue, a story about the increasing prevalence of mosquito-borne diseases cites the work of Oxford University scientist Janey Messina, who predicts that, because of rising temperatures and increased rainfall, the populations at the highest risk of illnesses such as dengue fever will grow “substantially and disproportionately in the most economically disadvantaged areas.”

Want to read more about creation care and indigenous peoples? The Rev. Rachel Taber-Hamilton explains why when speaking of environmentalism with indigenous people, you need to take into account their traditions, cultures, systems, and institutions. Dr. Andrew Thompson sums it up to explain why the work of the Church involves not only environmental stewardship, but also environmental justice and antiracism.

The Theology of Climate Change

Given all of this, there is little doubt that we should all be concerned for the future. But why has The Episcopal Church made creation care such a priority? Why are we, as people of God, particularly called to care for the less fortunate and the disenfranchised, as well as the natural world?

“Because God tells us to,” says the Rev. Rebecca Abts Wright, School of Theology professor of Old Testament and Biblical Hebrew. “It’s pretty simple, really. The Hebrew Bible makes it clear that the idea of community extends to the natural world and the people on the fringes, just as God’s care does. All of the books from Exodus to Deuteronomy are instructions about how to live in community, even before the people have land to live on. Living in community is the primary message of the Old Testament. And to do that, we have to care for creation, and for each other.”

Wright has found several ways, over the course of her career, to encourage her students to recognize their connection to creation. In addition to studying the Hebrew Bible’s stories and messages about community, for instance, her Old Testament students are required to maintain a weekly log in an assignment called The Land Project, which asks that they mark off and observe changes to a small parcel of land over the course of the academic year. “Some students hate it,” Wright says, “and some consider it life-changing. But at the very least, it forces each student to pay attention.”

The Rev. Dr. Rebecca Abts Wright, C.K. Benedict Professor of Old Testament.

The Rev. Dr. Rebecca Abts Wright, C.K. Benedict Professor of Old Testament.

Paying attention, it turns out, is precisely what the Bible calls us to do in Genesis 2:15, when the first human is placed in the Garden of Eden. “Most translations say, ‘The Lord God took the man and put him in the garden of Eden to till it and keep it,’” Wright explains, citing the work of theologian Ellen Davis on the Genesis text, “but the translation has been ossified in a way that doesn’t capture the actual Hebrew, which says that the man is put in the garden to pay attention and serve it. When you think about how we are meant to relate to the natural world, paying attention and serving creation is a great place to start. Remembering that working on the land isn’t a punishment, but rather what we are called to do, is a good second step.”

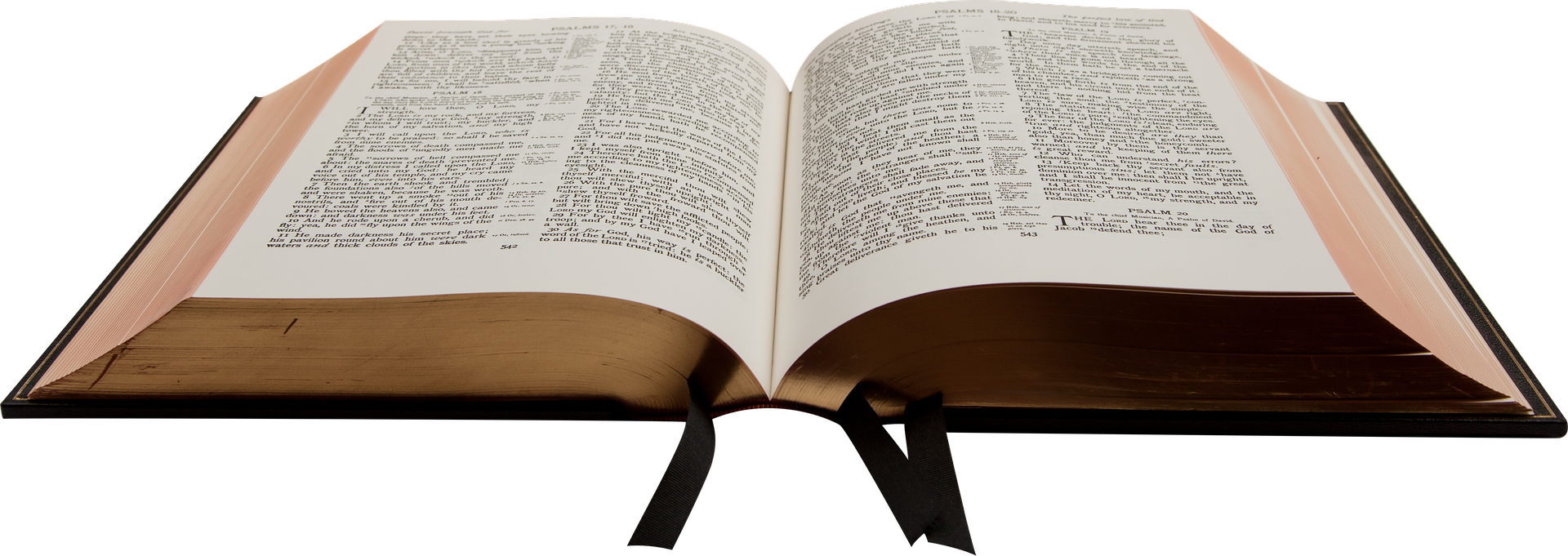

Answering the question of what to do with the Gospel is of particular concern for the Rev. Dr. William Brosend, professor of New Testament at the School of Theology and author of The Homiletical Question: an introduction to liturgical preaching, among other works. “The people we meet on the pages of the New Testament lived out the care of creation every day,” Brosend says. “Most people in antiquity had quite precarious lives. Not for nothing did Jesus teach them to pray, ‘Give us this day our daily bread.’ Because they were dependent on sun and rain and temperate weather to survive, it was second nature to care for creation.”

The Rev. Dr. William Brosend, professor of New Testament.

The Rev. Dr. William Brosend, professor of New Testament.

Brosend cites several parables illustrating the care for creation that was intrinsic to those who lived in the earliest Christian communities. In Matthew 13:24-30, for example, there is a story of weeds growing in a wheat field. “The servants want to pull them,” Brosend says, “but the owner of the field instructs them to let them grow alongside the wheat, because pulling the weeds prematurely could destroy the wheat. And when it is time for the harvest, the owner says that the weeds should be pulled first, and should be bound into bundles to be burned.” Those bundles, Brosend explains, point to the interconnectedness of human subsistence and nature in the New Testament. “The bundles would not have been burned as trash, but rather as fuel, because the goal of growing wheat is to make the daily bread, and to do that, you need fuel, a source of heat.” The story illustrates how creation sustains us in every way, not just by providing raw ingredients, but also the tools needed to transform those ingredients into food.

In addition to care for creation, Brosend explains, there is also a profound respect for nature in the stories of the New Testament. “Look at Luke 13:6-9,” Brosend says. “Jesus tells the story of a fig tree that fails to produce fruit. The owner wants to cut it down, but the gardener says, ‘Let it alone for another year, until I dig around it and spread manure on it. It if bears fruit next year, well and good; but if not, you can cut it down.’” This sort of approach to the natural world was commonplace in antiquity, Brosend explains, because the very lives of the people depended on nurturing nature. “Pray God we will learn, while there is still time to make a difference, that our lives do, too.”

Another lesson Wright impresses upon her students is the interconnectedness of human behavior and creation. “Human sin affects the entire world,” she says. “That’s a lesson of the prophets, who tell us over and over that the Earth mourns, the fields are laid waste, and the fig tree languishes, all because of human sin. If you look at Revelation, the last chapter ends with the tree of life, which has leaves for the healing of the nations. It’s the book end to the tree of life in Genesis. The Hebrew Bible makes it clear that we are deeply connected to the fate of creation, as well as to each other.”

Wright cites the Scriptural concern for marginalized citizens as another facet of our interconnectedness. “There was a way of taking care of one another that we seem to have forgotten,” she says. “In the Hebrew Bible, the edges and corners of every field belong to the poor. Those in need are able to come and take what they require, preserving both their lives and their dignity in the process. But when it comes to how we are living now, we’re making it impossible for people to make ends meet, much less retain their dignity. We’re denying even the corners and edges to the people who need them,” she says. “I think it would be useful for the Church to consider what the corners and edges, in our service and manufacturing economy, might be.”

Indeed, for The Episcopal Church, there is no consideration of creation care independent of concern for issues of race and poverty. The Rev. Canon Stephanie Spellers, Canon to the Presiding Bishop for Evangelism, Reconciliation and Stewardship of Creation, has explained the connection this way: “The face of suffering because of climate change and climate impact is so often a Black person, a Brown person, an Asian person, a Native person. ... Reality has begun to debunk this idea that climate change and concern about race are somehow separate, or that concern about poverty is separate from that.” Thus, Spellers explains, “We in The Episcopal Church have been very intentional about doing our work intersectionally ... the intersection of racism, environmental destruction, and poverty.”

In an effort to illustrate the ways in which poverty, race, and climate change intersect, The Episcopal Church has developed an overlay for the Asset Map.

The online map is interactive and allows the user to find location-based information, trends, opportunities, ministries, and stories. Now, Spellers explains, the map will also allow searchers to view the predicted impact of climate change “10, 20, and 30 years out. When you overlay that with communities of color and poverty, people can literally see the intersection.”

The Rev. Melanie Mullen, whom Spellers refers to as “the embodiment of that intersection,” reiterated the importance of the Asset Map in a recent Zoom conversation with St. Augustine’s Episcopal Church in Washington, D.C., pointing out that the map can not only let you see where air pollution will affect a specific area, but also when a parish that is currently “by the sea” might soon be better called “in the sea.”

What We Can Do

Mullen, Director of Reconciliation, Justice and Creation Care for The Episcopal Church, reminds us that all Episcopalians are called to work for justice in our Baptismal Creed. “We really, clearly lay out, ‘Will you pursue justice? Strive for peace, respect, and dignity of all humankind?’ If you say that to an Episcopalian, they will reflexively say, ‘I will with God’s help.’ We make a series of promises that lay out a vision of person and community. We have not been great at walking the walk, or even explaining how the connection between your pious church life connects to the community role, but we say it. We lay it out there. We say, “Jesus has a model for us to follow: Love your neighbor as yourself.

Mullen believes the Church has the ability to positively impact all aspects of creation care, and says that the active participation of bishops, dioceses, and individuals across the country, all of whom are impassioned, involved, and deeply invested in improving the status quo, is a very hopeful sign. One thing Episcopalians do very well, she says, is engage in respectful dialogue. “We are very good at pulling together the left and the right and finding common ground. Agreeability and civility have virtue, as does proselytizing through our actions. Civility helps hold us in community and in conversation to find solutions. Civility lets us stay close, even as we discuss difficult things.”

Mullen points to the ABCD tool set of Asset Based Community Development as an example of seeking solutions among the people who are impacted by any given problem. “We are very intentional about intersectional justice, and about hearing all of the voices,” she says. “And there are so many local networks in the Church that you are never alone. The Episcopal Church has a special charism to call people to intersectionality, to be present in reconciliation and building beloved community. We live into the ethic of justice that The Episcopal Church does so well, and we do it because of Jesus.”

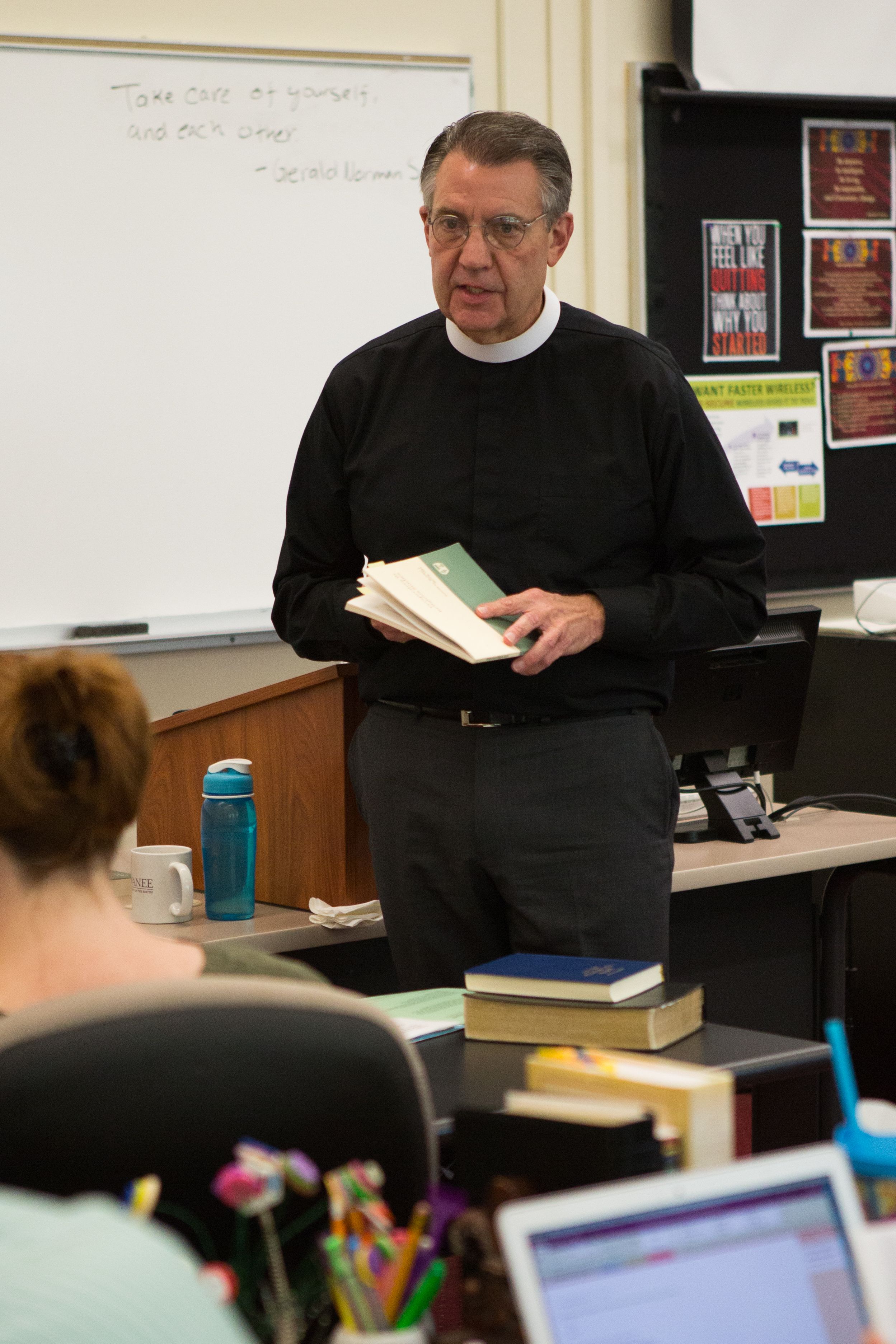

St. Andrews Seattle Plans for Grounds: they have a very active Creation Care ministry, have installed solar panels, and created an organic garden. The layout of the grounds is from their website. A plan for the grounds of St. Andrews, Seattle WA

St. Andrews Seattle Plans for Grounds: they have a very active Creation Care ministry, have installed solar panels, and created an organic garden. The layout of the grounds is from their website. A plan for the grounds of St. Andrews, Seattle WA

For Brian Sellers-Petersen, who also serves as coordinator of the Church’s Good News Gardens program and as Agrarian Evangelist for The Episcopal Church, the Church has a special calling to all three tenets of creation care for one particular reason. “We have a special responsibility to stewardship of the land because we, as a church, probably own more land per communicant than pretty much any other church. So much of that land belonged to Native Americans, and so many of our institutions benefited from slave labor, that we have to be involved in issues of racial reconciliation and reparations and agrarian ministry and environmental justice.”

Sellers-Petersen grew up visiting his grandparents’ farms in rural Nebraska, but was discouraged from attending agricultural college by his parents, who knew firsthand what a difficult life farming can be. After graduation, he went to South Africa, where he worked for the Anglican Church. “This was during apartheid,” he says, “when the church was one of the few safe places for different races to mix.” After South Africa, Sellers-Petersen went to work in international development, spending eighteen years with Episcopal Relief & Development. In Africa, he saw how dramatically the Anglican Church leveraged their land holdings for the benefit of the surrounding communities. “In Uganda, for instance, the land is mostly held by the government with a small portion titled to the Anglican church. And that land, the church’s land, is viewed by the local people as ‘ours’ because it is the land they have access to without government involvement. The church's land is viewed as a whole community asset.”

This idea, that a church's land might actively benefit, and invite connection with, the community in which it is located, underpins the work of the Good News Gardens. “We have churches like St. James-Santiago in Oakland, California, that have turned an unused parking lot into a community garden,” Sellers-Petersen says. “The diocese of Los Angeles has a living labyrinth that is half ornamental plants and half edible plants. At one point and maybe still today, St. John’s Parish in Lynchburg, Virginia, had a farmer’s market that sold produce raised in parishioners’ home gardens to members and neighbors. Half the money went to Episcopal Relief & Development for small-scale agricultural products, and half went to the local food pantry. The whole point is to think creatively, and use the assets you have to benefit your community.”

Interest in the work of Good News Gardens has grown enormously during the pandemic as people have looked for ways to help their neighbors in need. Community gardens are a natural fit for Christians looking to share the Gospel, Sellers-Petersen explains. “Have you ever noticed that Jesus never told stories about being a carpenter? That's because it was a side gig. With the exception of the very elite, everyone in Jesus's time was a farmer. Our sacraments are agrarian sacraments. Our Eucharist is a gathering at the table. When you have a church garden, you’re inviting the community to witness first-hand the Good News. Every church, and every individual in the Church, should be involved in agrarian ministry!” For a parish or individual still contemplating a foray into agrarian ministry, he has some simple advice. “Just start somewhere, whether it’s with a window box full of flowers or a container full of plants.”

An unused parking lot converted to a community garden at St. James–Santiago in Oakland, CA.

An unused parking lot converted to a community garden at St. James–Santiago in Oakland, CA.

The Presiding Bishop, Sellers-Petersen says, deserves much of the credit for interest in programs like Good News Gardens, as well as reconciliation and racial justice. “Bishop Curry has changed our understanding of evangelism. He embodies the idea that how we live is evangelism. He encourages the Church to recognize its past, like the fact that so much of the Church’s land first belonged to indigenous people. He encourages us to ask questions, like ‘How do we recognize, honor, and make reparations for indigenous land?’ and ‘What’s the best way forward?’”

Produce from the Community Garden of All Souls Episcopal, Ashland, VA.

Produce from the Community Garden of All Souls Episcopal, Ashland, VA.

Sewanee and the Environment: Making a Difference Far and Wide

Dr. Robin Gottfried, founder and director of the Center for Religion and the Environment at Sewanee, believes the University is uniquely positioned to address those questions, and others like them. “We have the Domain, the School of Theology, and a robust Environmental Studies program. What other University can claim all three?”

Gottfried began his career teaching economics at St. John’s University, a Benedictine institution. Just before leaving for Guatemala on a Fulbright scholarship in 1979, Gottfried gave a talk on The Image of Man and Economics at St. John’s, and realized that the individualism promoted in economic theory and the concern for community asserted in his faith were at odds. Soon after arriving in Latin America, Gottfried was given a collection of papal social encyclicals and asked to give a talk on the energy crisis that was unfolding at the time. In preparing for the talk, Gottfried looked at the impact of energy policy on public health and the environment, and a question began to nag at him incessantly: “How does my chosen discipline of economics fit in with my faith? The two just didn't jibe.”

Robin Gottfried stands with the participants of the Deep Green Faith conference.

Robin Gottfried stands with the participants of the Deep Green Faith conference.

As a boy, Gottfried’s family had taken regular camping trips in Shenandoah National Park, and it was there, in nature, that he had felt the presence of God. Yet when Gottfried began questioning how economics and Catholicism could be reconciled and incorporate his love for nature, “sustainability” was not yet a common term, much less a field of study. There were only three books published on economics and the environment when Gottfried attended graduate school, he recalls, and he read them all. “I got in on the ground floor of this field,” Gottfried says. “When I came to Sewanee in 1982 as a professor of economics, I was allowed to create a course on environmental economics. From there, my interest just continued to grow. Subsequently, I also attended the very first conference on the field of ecological economics that was held at the World Bank.”

When Fred Krueger, executive director of the National Religious Coalition on Creation Care and founder of the Opening the Book of Nature contemplative program, gave a weekend program at the DuBose Conference Center, a partnership and friendship was born. Around the same time, Gottfried was researching biblical environmental theology, and began reconsidering the conflict he had seen as inherent to economics and faith. “What I realized,” he says, “is that there is not conflict if you start from scratch and rethink things. The fundamental question to ask is, ‘What does God want us to do?’ Then you go from there.”

The Center for Religion and the Environment has grown significantly over the years, and helped design a graduate degree program for the University. The Center also now offers both an undergraduate minor and a non-credit certificate program in Contemplation and Care for Creation. While the pandemic has forced many of the Center's programs to adopt a hybrid or strictly virtual form, the online presence has only broadened the Center’s ability to reach other dioceses, churches, individuals, and groups. “We want to look at what it means to make your whole life a prayer, and to understand nature as part of your faith. You can do that where you are,” Gottfried explains. “Scripture reflects a three-way covenant between God, the land, and the people. Caring for creation shouldn’t just be a committee project. Nature should be part of our lives, and part of our relationship with God.”

Gottfried sees Sewanee, with its unique geography and abundance of scholarship in both theology and environmental issues, at the forefront of a much-needed renewal in the Church. “If we become a deep green Church, with creation part and parcel of who we are, we can heal some of the alienation from God and creation that plagues us,” he says. “We have the opportunity to become a truly God-loving people, and to move towards the shalom of a renewed kingdom.”

Dr. John Gatta, professor of English emeritus at Sewanee, agrees that the Church has both an opportunity and an imperative to help create a world in which loving nature, and one another, is at the center of everything we do. “The Church’s conversation around creation care usually centers on ethical or public policy concerns, which many secular groups are already well equipped to address, whereas I believe the Church’s special vocation in this sphere is more fittingly doxological, theological, and visionary,” Gatta says. “There is an opportunity to create a vision of the world that is suffused with divinity, and to re-envision how our Christian doctrine is at the center of our concern for the environment.”

For Gatta, literature has always provided a portal and a means of access to theological matters. As a professor at the University of Connecticut, one of his graduate students suggested that Gatta create a course about literature and the natural world, which Gatta developed and co-taught with Sewanee alumnus Samuel Pickering. This course reinforced Gatta’s belief that imagination is “crucial to the whole enterprise of seeing the interconnectedness of all things, and how heaven and earth truly are full of God’s glory. The imagination, as Samuel Taylor Coleridge conceived it, is not merely make-believe, but rather an ecology of the mind. It’s how we see that all things are related, and that nature is suffused with a religious dimension.”

This inter-relatedness of nature and religion, Gatta says, is at the heart of creation care. He points to the Nicene Creed, and the phrase maker of heaven and earth, of all that is seen and unseen, as one of the ways the liturgy reminds us that the creation we are called to care for encompasses all aspects of our world, not only the pleasing parts. “If you really reflect on this phrase,” Gatta says, “you find that this is truly a creation liturgy, and a reminder that the natural world is beauty and wonder and grandeur, but also messiness and suffering. It is the wonder of creation, but also the disproportionate effect on people of color and disadvantaged communities.” We do not get to pick and choose the parts that are the least challenging, Gatta explains. “Just as Holy Week is infused with the glory of the Resurrection, it also contains profound suffering and pain. We have to take in both to fully experience Holy Week. The same is true for creation care.”

Gatta has authored several works on the interplay of imaginative literature, theology, and the natural world, including Making Nature Sacred: Literature, Religion, and Environment in America from the Puritans to the Present and The Transfiguration of Christ and Creation. “Literature,” he says, “is a way into imagination. After all, you can read the Gospel, but what are you going to do with it? One of the things that makes Sewanee so fortunate is the University’s very strong rooting in the humanities, and the ability to incorporate literature and fine arts and philosophy into the study of both the environment and religion, in an attempt to answer that question.”

Sewanee has taken several steps that honor the connection between creation, food, and spirituality under the guidance of Rick Wright, director of Dining Services. “Food is a commodity, but it shouldn't be,” Wright says. “A zero-sum mentality shouldn’t apply to food, because if you think of life as a Venn diagram, food is at the center, touching everything. Sharing a meal, and the fellowship in that act, is at the center of community, so how can we think of food as a commodity if we want to live in community?’

The community around food is something Wright began cultivating in Sewanee a decade ago, when he began building relationships with local farmers to establish a pipeline of produce grown within a seventy-mile radius of the University’s Domain. Once suppliers were in place, Wright retrained the kitchen staff to prepare meals using that food rather than pre-packaged goods, and he also set about improving working conditions for University Dining’s employees. “You can’t make good food if you’re not happy,” Wright says. “I believe that in order to create good food, you have to first create an environment where good hearts can thrive. You have to cultivate gratitude.’

Rick Wright, director of Dining Services.

Rick Wright, director of Dining Services.

One of Wright’s most important missions at the University has been to reduce food waste. The Kitchen to Table program, run in conjunction with Otey Parish and the parish’s Community Action Committee, portions leftovers from McClurg dining hall into single-serving meals. The meals are sealed with a machine that was purchased with help from the Rotary Club, and then distributed to those in need all over the Plateau. “Anyone can stop at Otey and get a meal,” Wright explains. “Generally, those numbers run between two and three hundred meals a week. There’s also a Summer Feeding Program, which is part of VISTA, that used to serve about 9,000 meals per summer. Last year, that same program served around 50,000 meals. Need really escalated during the pandemic.”

Professor Rebecca Abts Wright, no relation to Rick Wright, is a huge advocate for both Otey Parish’s programs and the Summer Feeding Program. “Anyone in need can sign up to receive the meals in the Summer Feeding Program,” she says, “and that’s an important point. There are no necessary qualifications. You simply state your need, and get help. In the Bible, the poor identify themselves, and retain their dignity by doing what they’re able to do to help themselves to the edges and corner. But there is no means test. As soon as you put a means test in place, you’ve broken community.” The theme of food, she reminds us, is found everywhere in Scripture. “A metaphor for the kingdom of God in the Bible is a feast, an abundance of food,” Wright says, “which ought to remind us how very central food is to fellowship and living in community.”

Rick Wright’s belief in community stems from a lesson his father taught him when he was a boy: No sleepwalking. For Wright, this means living with intention, and involves meditation, cultivating gratitude, and educating students and staff alike about food’s health-giving properties, particularly when that food is locally-sourced and organically grown. Not surprising for a man who quotes Wendell Berry, Wright’s decision to join the University staff a decade ago was in part motivated by literature. “At the time, Sewanee had just made Michael Pollan’s The Omnivore's Dilemma required reading for incoming students. That signaled to me that Sewanee presented an opportunity to do some education around food, and a like-mindedness about reducing waste, respecting the food, and sharing leftovers.”

There is still room for improvement on campus, Wright says, pointing to recycling and composting programs that can be expanded, and he would like to see the commitment to local farmers continued. Sewanee is fortunate, he feels, to be in a place where the University and local farmers can work together to put healthy food into the dining hall and money into the local economy.

The bottom line when it comes to creation care, Wright says, is this: “Everything is connected. And while a lot of systems are set up to support mediocrity, what we are doing here at Sewanee is striving for excellence.”