On the Trail of

Hudson Stuck

In a new book, Patrick Dean, T’06, explores the life of the Sewanee alumnus who co-led the first successful summit of the continent’s tallest mountain.

In a new book, A Window to Heaven, Patrick Dean, T’06, explores the life of Hudson Stuck, an 1892 graduate of the University of the South’s School of Theology, who is best known for organizing and co-leading the first team to summit North America’s tallest mountain, Denali, in 1913. Dean investigates what drove Stuck, who was almost 50 years old at the time, to put himself through the misery and risk of summiting the remote and treacherous 20,000-foot mountain. The answer that emerges from the pages reveals a man wired for adventure and fueled by an intense desire to live a life of “usefulness to others.”

Stuck was born in 1863 in Paddington, London, England. At the time, London was already densely populated by millions of people, and had been the largest city in the world for much of the 19th century. It was also a city on the cutting edge of technological and economic dominance. Earlier in the year of Stuck’s birth, the London Underground railway opened to the public. By contrast, the United States wouldn’t see its first working subway until 1897, in Boston.

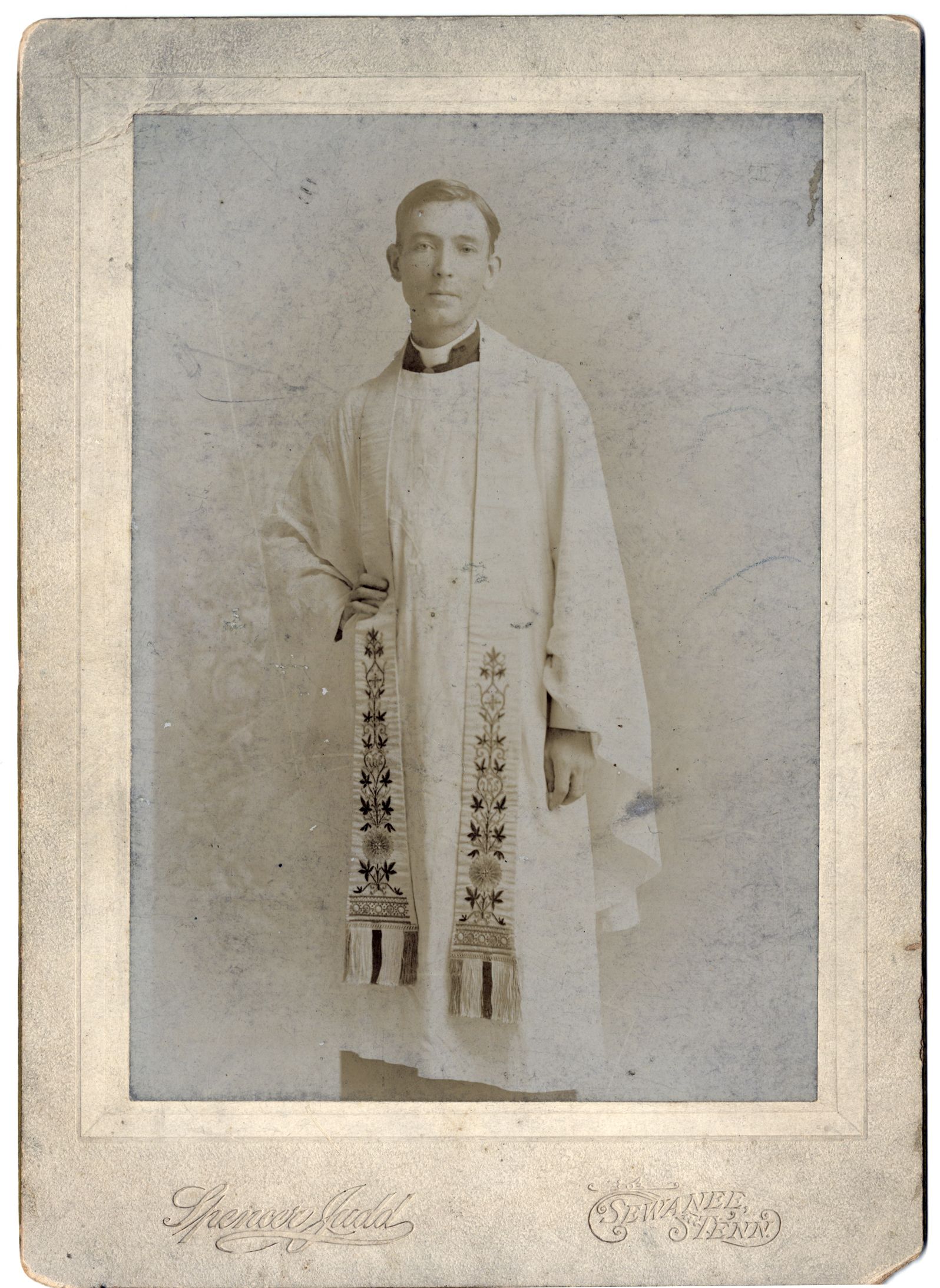

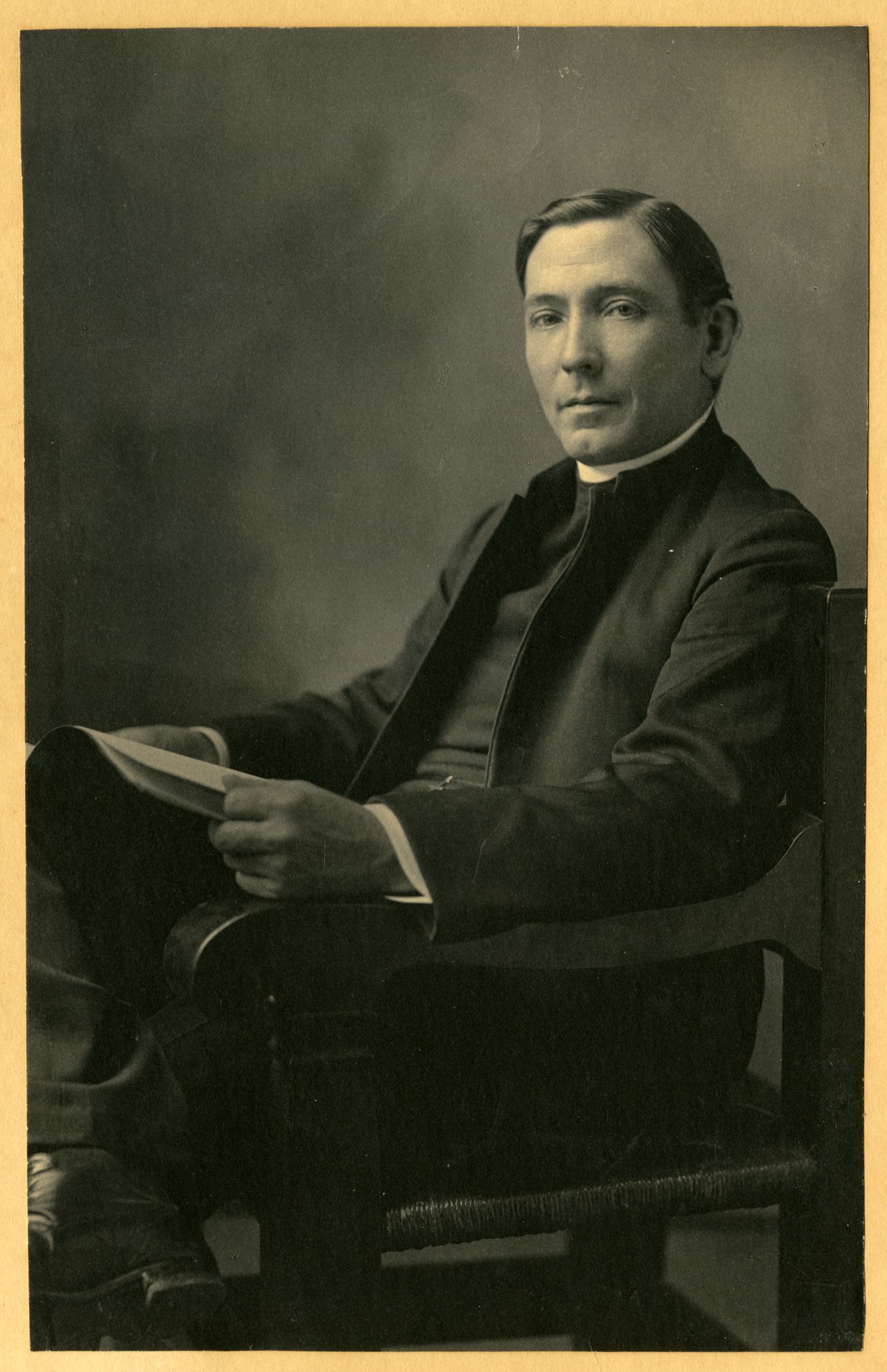

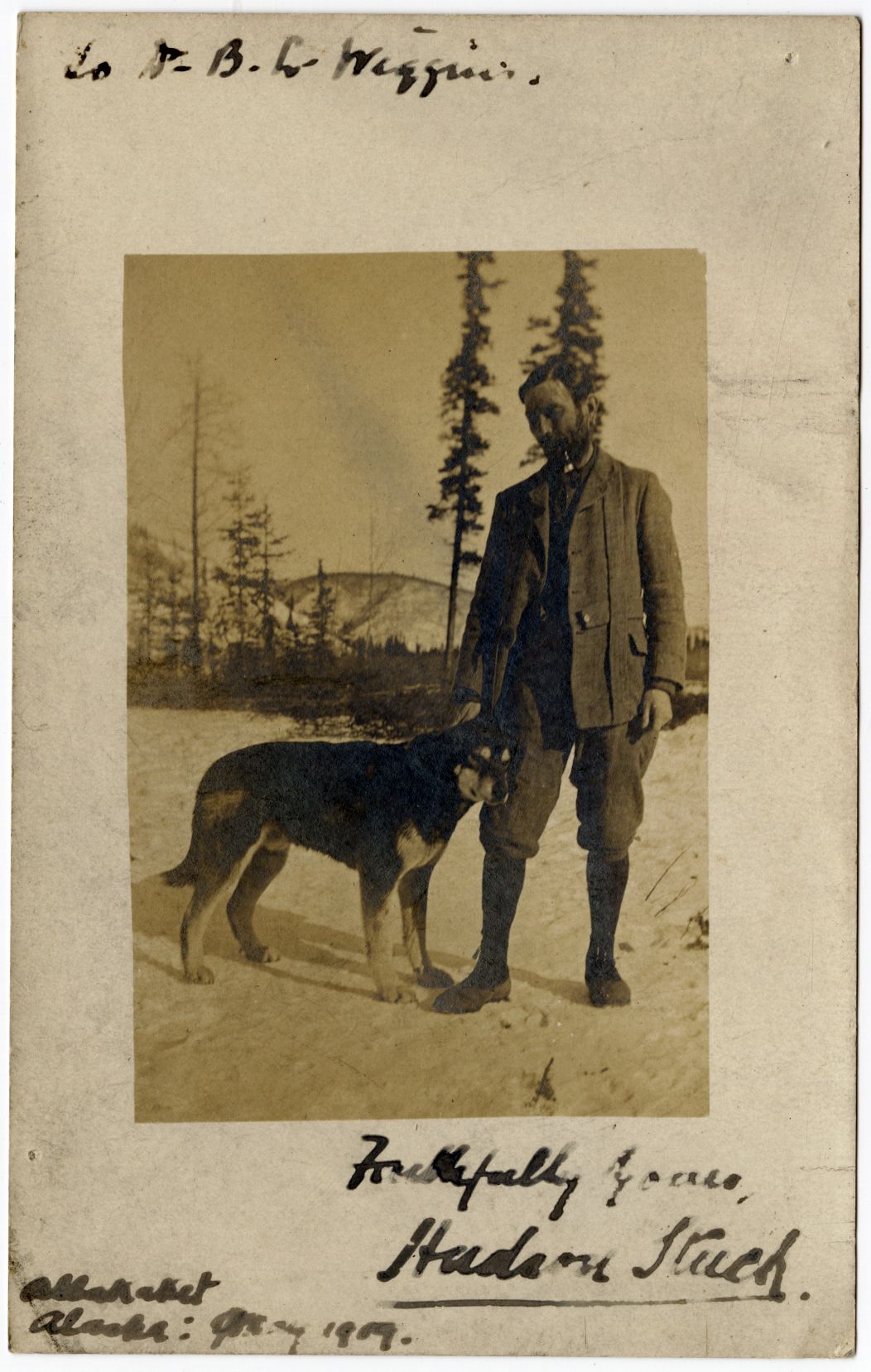

As a child, Stuck, a voracious reader, immersed himself in stories of polar exploration in books left to him by his uncle. As legend has it, Stuck longed to leave the crowded city for “wide open spaces,” and a coin flip led him to immigrate to the United States in 1885, at the age of 22. He headed first to Texas to work as a cowboy, and also took work as a teacher in tiny schools on the Texas frontier. In 1889, a scholarship led him to seek a theology degree at Sewanee, after which he was ordained as an Episcopal priest. After a time in Dallas, Texas, where perhaps he found himself feeling too comfortable, Stuck left on a new adventure to become “archdeacon of the Yukon and the Arctic” in Alaska, in 1904. He got straight to work by starting a mission and hospital in Fairbanks, and then began to visit mission churches across a vast territory of wilderness by dogsled. Denali, often on the horizon, began to beckon him.

Many decades later in Jackson, Mississippi, a then-25-year-old Patrick Dean discovered Hudson Stuck’s first book, Ten Thousand Miles with a Dogsled, at Lemuria Bookstore, where he worked for a time. Dean says he’s not certain that he noticed at the time that the book is dedicated “to Sewanee, the college on the mountain top.”

After suffering a family tragedy as an adolescent, Dean found focusing on his studies difficult during high school and college, and had a hard time keeping his grades up. But his dream of becoming a writer, and a strong appetite for reading, provided the foundation for a career as a teacher and a political media director. Eventually, seeking a change, Dean and his wife, Susan, decided to look for a new place to settle. They wanted to be in a small college town with easy access to nature, and they decided on the Sewanee area, where they moved in 1999. While teaching at St. Andrew’s-Sewanee School, Dean decided to pursue a master’s degree at the School of Theology, as he admits, to prove to himself that he could do it. He chose to write his graduate thesis about Hudson Stuck.

Since 2012, Dean has worked as a freelance writer, specializing in nature writing, stories about outdoor athletes, and environmental advocacy. All the while, his fascination with Hudson Stuck’s story grew as he amassed more knowledge via the University Archives. Years before his death, Stuck gifted a large collection of books and notebooks to the University. Also on file are dozens of letters that Stuck wrote to the University to express his opinions about various topics. For example, he was not very happy with the University’s enthusiasm for the new sport of American football, complaining to Vice-Chancellor Benjamin Lawton Wiggins about the academic cost of the travel undertaken by the legendary 1899 “Iron Men of Sewanee” team.

In 2019, Dean was ready to attempt to climb his own mountain: writing his first book. Equipped with knowledge from years of researching Hudson Stuck, he wrote a book proposal and submitted it to an agent. Ultimately, Pegasus Books offered him a contract. Dean was looking forward to spending the early part of 2020 traveling to Texas and Alaska to visit the places where Stuck had left his mark on the world, but the COVID-19 pandemic upended his plans. Like most of us, Dean had to adapt to life under stay-at-home orders and research and write from his home in Monteagle. The book that emerged from his efforts reveals that Stuck was, in many ways, a man ahead of his time.

As the heated national conversation over racial justice and representation intensifies, there is a lesson in Stuck’s example. The mountain that Stuck climbed in 1913 was known officially as Mount McKinley, named after President William McKinley, by the white settlers who had moved to the Alaskan frontier. But, as is true across the North American continent, the land has been continuously settled by native peoples for many thousands of years. As Dean explains, Stuck advocated for and cared deeply about the native people of Alaska, and grew increasingly concerned about the impact that white settlers were having on their ways of life. Mount McKinley already had a name.

By choosing to title his firsthand account of the expedition to the summit of the mountain The Ascent of Denali, Hudson Stuck took a stand about how he believed that the mountain should be represented. In the foreword to this work, published in 1918, Stuck writes, “Forefront in this book, because forefront in the author’s heart and desire, must stand a plea for the restoration to the greatest mountain in North America of its immemorial native name.” Stuck would not live to see this dream realized, but in 2015, then Secretary of the Interior Sally Jewell declared “Denali” the official name of the continent’s tallest mountain.

Stuck (bottom row, third from left) with fellow members of the University of the South Magazine staff, in 1890 or 1891.

Stuck ministers to native Alaskans in his role as archdeacon of the Yukon and the Arctic.

Stuck traveled by dogsled to reach far-flung and isolated missions in Alaska.

Back on our Mountain in Sewanee, today there are still traces of Hudson Stuck, in the form of a statue on the high altar, as well as a plaque dedicated to his memory, in All Saints’ Chapel. As for Patrick Dean, in addition to writing, he has been serving as the executive director of the rails-to-trails nonprofit Mountain Goat Trail Alliance (MGTA). The MGTA has been working to turn the former “Mountain Goat” railroad into a 35-mile paved cycling and footpath connecting communities on the Cumberland Plateau. The former railroad, which was built in 1856, was used to haul away coal from mines in towns like Tracy City and Palmer. It also carried passengers, and very likely was how Hudson Stuck made his way to Sewanee all those years ago, forever connecting his life to everyone who has called the Mountain home. Sewanee provided Hudson Stuck the education and experience he needed to reach his dreams of a life well-lived. Patrick Dean has breathed new life into Stuck’s legacy in his thrilling first book.

A Window To Heaven: The Daring First Ascent of Denali, America’s Wildest Peak, will be released on March 2, 2021.