Mr. Hospitality

Rondal Richardson’s journey from being the man behind the curtain for some of country music’s biggest stars to blazing a path in entertainment philanthropy—connecting celebrities with worthy causes and raising millions of dollars in the process—is a testament to the power of a generous spirit and the art of giving back.

Rondal Richardson, C’91, has seen plenty of Garth Brooks concerts, maybe more than anyone else. But there’s one show he remembers most fondly, an unusual show Brooks did at the Pyramid Arena in Memphis in 1998 at the height of the superstar musician’s international acclaim. Brooks is one of the top-selling solo artists of all time, and he typically sells out huge venues like the 20,000-seat Pyramid, but only 100 people showed up to this particular concert. They were all patients from St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital, along with a few doctors and nurses in support roles. For two hours, Brooks played his heart out. He gave as much to those kids—many of them in wheelchairs and connected to IV poles—as he gave later that night to a Pyramid audience packed to the rafters. “That was one of the first times I saw entertainment philanthropy,” says Richardson, who worked for Brooks for nine years as a marketing executive and accompanied him on shows around the world. “I saw the power of what he did. That was an important day.”

Today, Richardson, a veteran of the music industry for three decades, focuses exclusively on entertainment philanthropy at the Community Foundation of Middle Tennessee. His mission, in a nutshell, is this: to leverage his extensive contacts in the music world (in addition to his stint with Brooks, he was Wynonna Judd’s general manager for eight years) to connect wealthy stars with nonprofit charities doing good work. Over the last 17 years, Richardson has worked with everyone from Carrie Underwood and Darius Rucker to Kelly Clarkson and Rascal Flatts, and dozens more artists, to raise over $225 million for nonprofits around the world. Last month, at Marathon Music Works in Nashville, he was recognized for his pioneering work in entertainment philanthropy with a Leadership in Music Award from an organization called Musicians on Call. He shared the stage with country star Kelsea Ballerini, who received an award for her years of playing at hospital bedsides. Both were feted with performances from Wynonna, Trisha Yearwood, and Tiera Kennedy, among others.

Richardson uses the word “hospitality” a lot. It’s what drives him, in both work and life. “Hospitality means welcoming,” he says. “It means everyone has a seat at the table. It means being a part of something bigger than yourself.” When Richardson watched Brooks performing for those young patients, he was witnessing hospitality. When he helps musicians tap into their philanthropic selves, that’s hospitality too. Even the award he was given recently, that was a form of hospitality. “No one gets into this work to be recognized,” he says. “When we’re doing hospitality, we’re living our best lives. This award was about community, it was not an individual award.”

Richardson (left) with comedian Theo Von, country superstar Morgan Wallen, Amy Fair, and Chris Johnson at a benefit concert for Tennessee flood victims in 2021. Photo by David Lehr

Richardson (left) with comedian Theo Von, country superstar Morgan Wallen, Amy Fair, and Chris Johnson at a benefit concert for Tennessee flood victims in 2021. Photo by David Lehr

At every point in his life, from his growing up in Tennessee, to his time at Sewanee, to his career in the music business and beyond, Richardson has been inspired by the idea of hospitality, and he’s tried to live a life fully engaged in it.

Richardson was born in Shelbyville, Tennessee, but moved to Franklin, a suburb of Nashville, when he was 13. His father worked as an environmental engineer and was a pioneering conservationist. He helped create the marshland exhibit at the Tennessee Aquarium. His mother was an elementary school teacher. Because of his father’s work and passions, and because politics in Tennessee were simpler back then, his family was constantly throwing dinner parties attended by various dignitaries, everyone from Gov. Lamar Alexander to former Sen. Al Gore Sr. “I was mesmerized by my parents’ gift of hospitality,’ he says. “My parents always stayed neutral. Everyone had a seat at the Richardson table, no matter your views."

Richardson was exposed to Sewanee from an early age. His parents honeymooned in Monteagle in the 1950s, and the family often picnicked on the Domain and spent Easter weekends at the Sewanee Inn, attending services at All Saints’ Chapel. “My dad loved the rock, and he loved the forests. He hoped by osmosis I would fall in love with Sewanee.” In high school, when Richardson had a cross country meet at Sewanee, a teammate’s older brother, a Sewanee student, invited them to dinner at Gailor Hall. “As a 17-year-old, I remember feeling so welcomed,” he says. “It was like Sewanee was breathing into me: ‘You belong here.’ We were introduced to all the pretty girls, all the fraternity brothers, it felt like I won the lottery.”

Considering these influences, when it came time to pick a college, few other places stood a chance. Richardson loved his small private high school in Franklin, Battle Ground Academy, and he similarly wanted a small college experience. He turned down a scholarship at the University of Florida to attend Sewanee.

Richardson compares his experience on campus to the movie The Dead Poet’s Society. He found the English and political science professors “absolutely intoxicating.” Politics Professor Rob Pearigen, C’76, was so influential that Richardson chose the subject as his major (Pearigen was also dean of men at the time; he now serves as vice-chancellor and president of the University). “Rob was the first adult who ever really saw me,” he says. “He finds your superpower and harnesses it for good.” With Pearigen’s encouragement, Richardson was soon involved with organizations and committees all over campus. He was head proctor. He was commander of his fraternity, Sigma Nu. Richardson was also in a class of exceptional students, folks like Jon Meacham, the Pulitzer Prize–winning historian, and Meredith Walker, who booked musical acts on Saturday Night Live for years before going to work for Amy Poehler. “I was surrounded by leaders,” he says. “It was a magical class. It made you want to try harder.”

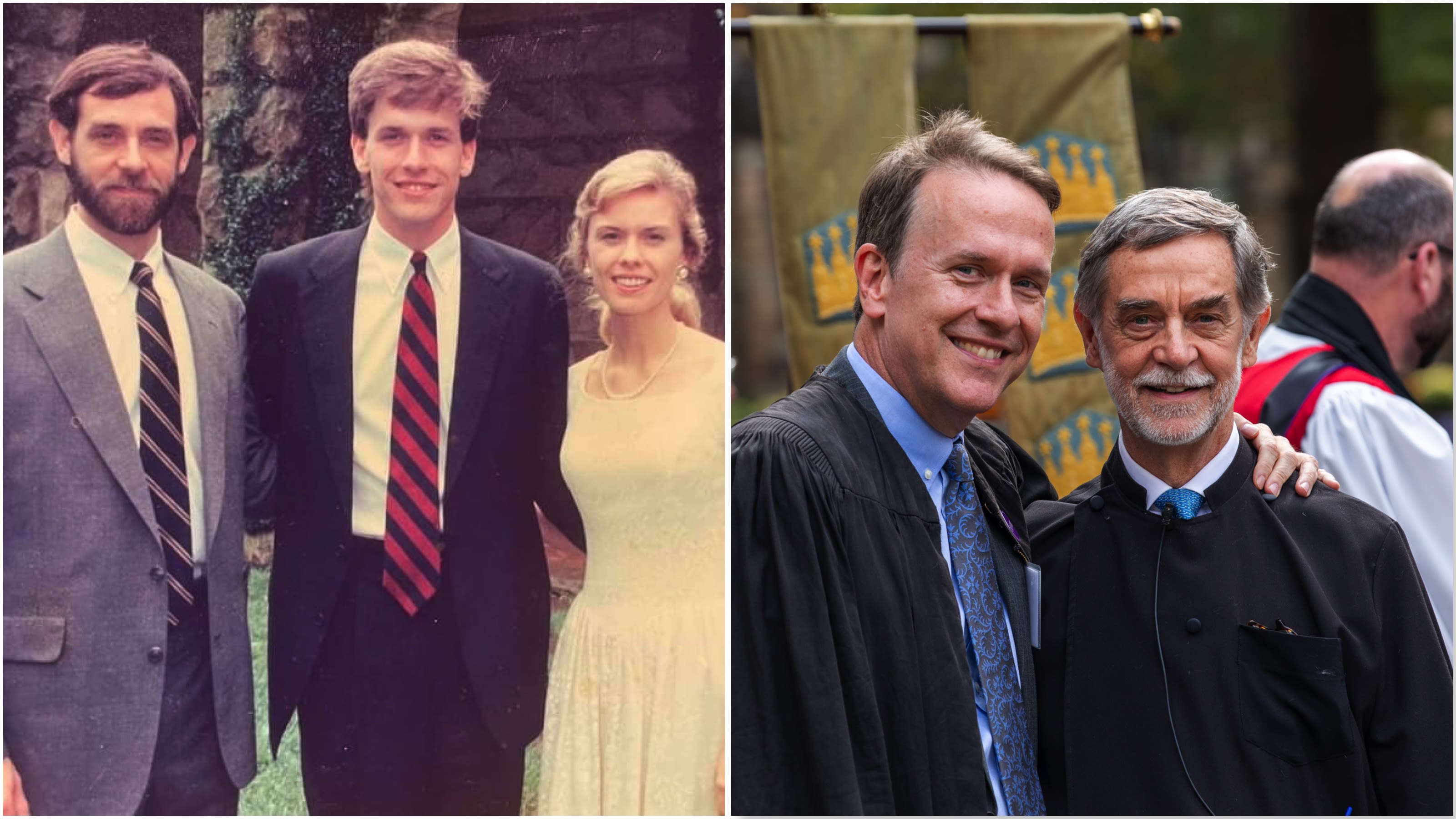

Left: Richardson with Rob and Phoebe Pearigen at his graduation in 1991. Right: Richardson and Rob Pearigen at Pearigen's installation as the University's 18th vice-chancellor in October 2023.

Left: Richardson with Rob and Phoebe Pearigen at his graduation in 1991. Right: Richardson and Rob Pearigen at Pearigen's installation as the University's 18th vice-chancellor in October 2023.

At the end of his college career, Richardson was awarded the prestigious Algernon Sydney Sullivan Medal, an award for character and service to humanity. “That was special,” he says. “It was really a fire starter. I remember thinking, ‘If they think I can do this, maybe I can.’”

When Richardson was still in high school, a company called Crom Tidwell Merchandising came to campus to recruit someone to sell concert merchandise for Ricky Skaggs and the Judds Tour in 1986. Richardson has always been a huge music lover and he took the job. Starting the summer before his freshman year at Sewanee, and then continuing every summer during college, Richardson crisscrossed the country, selling merch at concerts. He met stars of all kinds: Ashley Judd, Don Williams, Eddie Rabbit, Sweethearts of the Rodeo. He also met Brooks. “Garth was the king of hospitality, more than anyone I’d ever met,” he says. “He would sign autographs for hours after a show. He had this energy with fans, with colleagues, with friends of, ‘If I can experience this, you can too.’ He made everyone believe the music belongs to all of us.”

After graduating from Sewanee, Richardson hired on full-time with Crom Tidwell and focused almost exclusively on one client—Brooks. Their nine-year run together was mind-blowing, as Brooks radically changed the way country music was perceived worldwide. He wore a wireless headset and ran around the stage. He smashed guitars. He sold out venues that had never been sold out by a country artist, like Wembley Arena in London. He appeared on a tribute album to the rock band KISS and played one of the group’s songs, “Hard Luck Woman,” on the Tonight Show with Jay Leno. He played New York’s Central Park for more than a million people, the largest concert in the park’s history. “I learned the music business from this guy,” Richardson says. “It doesn’t get any dreamier.”

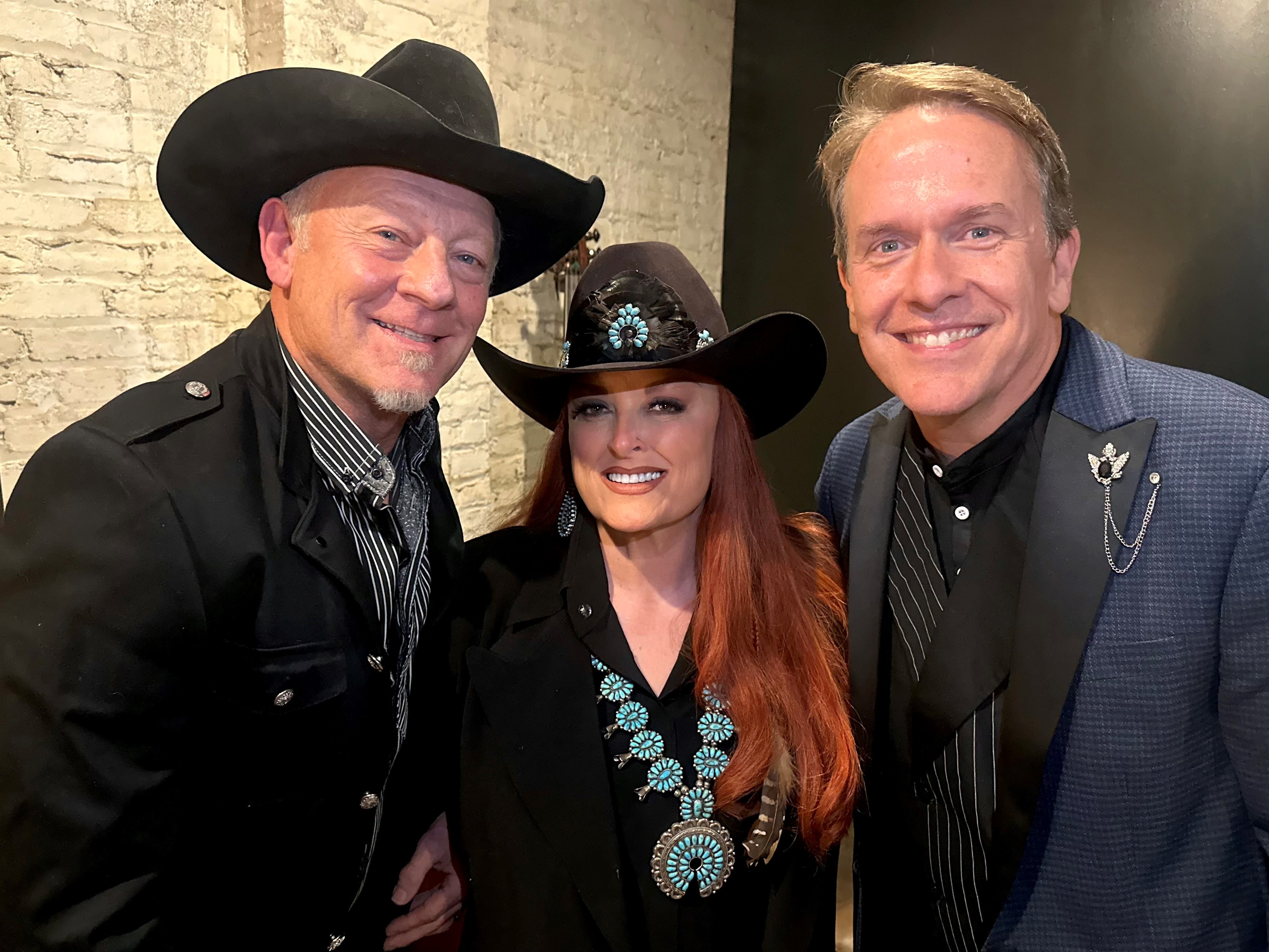

Richardson (right) worked with Wynonna Judd for eight years, during which the country superstar sang at both the Super Bowl and the White House.

Richardson (right) worked with Wynonna Judd for eight years, during which the country superstar sang at both the Super Bowl and the White House.

Richardson’s eight-year run with Wynonna Judd was equally impressive. He got her gigs at the Super Bowl (she sang “God Bless America”), on Oprah, and at the White House to play for President George W. Bush. She sang Elvis Presley’s “Burning Love” on the popular animated movie Lilo and Stitch. But his most important moment with Judd came in 2006 when the musician in a single day raised nearly $1 million lobbying politicians on behalf of children with AIDS. “Walking with her through those rooms to raise money, that affected me,” he says. “It’s like my feet weren’t on the ground.” And Judd noticed. “I saw a different gear in you with this charity work,” she told him. “I think this is what you were born to do.’”

In 2007, Richardson started Greater Purpose Productions with the idea of guiding musical stars in their philanthropic needs. No one had ever really done this before, and he wasn’t sure where to start. At home, he had sticky notes all over his wall. Some had the names of entertainers—Wynonna, Amy Grant, Reba McEntire, etc. Others had the names of nonprofits—Habitat for Humanity, Save the Children, Sierra Club. The sticky notes would shift around the wall. He had limited success, and initially he couldn’t figure out how to earn a proper salary. “I did this one project for a charity,” he says, “and they gave me a lasagna as compensation, to thank me.”

After three years of fits and starts (there were successes, like linking Carrie Underwood with the dog-food brand Pedigree to build an animal shelter in Oklahoma), he got a call out of the blue from Vanderbilt University. Vandy wanted a liaison to the music industry, someone who could encourage entertainers to donate to projects at the university’s Monroe Carell Jr. Children’s Hospital. For his part, Richardson figured the job could give him data to answer some core questions. “Is the music industry really philanthropic?” he wondered. “Is entertainment philanthropy a real thing? Is there a sustainable business model? I’d been doing this for three years, and I still didn’t have the data to answer these questions.” Over five years at Vandy, he was able to answer these questions with a resounding “yes.” During his stretch there, Richardson raised $25 million from more than 100 artists to build a new floor for the hospital. He got Ryan Seacrest to build his 10th Seacrest Studios in the hospital. These are multimedia broadcast facilities Seacrest builds in children’s hospitals to bring concerts and entertainment to young patients. Taylor Swift performed at the grand opening.

When Richardson joined the Community Foundation of Middle Tennessee six years ago, he realized he had arrived at the place where he could fully realize his life’s mission. At CFMT, he has linked more than 100 artists and athletes with charities around the world and seen more than $30 million go to fund all manner of important causes. “I’m just the guy behind the curtain, helping the magic happen,” he says. “It’s the best job I’ve ever had. I get to help people do generous things. It’s hospitality.”