In Pawleys Island, Bones Find Peace and Take Their Final Rest

The sun shone predictably bright and hot on the afternoon of May 23, 2021, the day of Pentecost. In Pawleys Island, a coastal resort on the Waccamaw Neck peninsula of South Carolina, live oaks and Spanish moss offered spotty shade to a crowd gathering at the cemetery of Holy Cross Faith Memorial Episcopal Church. Some early arrivals had claimed a spot under the green tent provided by Ridgeway Funeral Home.

The scene would not have seemed too remarkable to beachgoers in their cars, politely waiting for the funeral procession to finish crossing Highway 17 from the main part of the church campus to the cemetery—except this was no ordinary crowd. It was large, at least a couple hundred people. The stopped traffic might also have noticed the sheer diversity of the group and their clothing: clergy in surplices, preaching gowns, and cassocks of a variety of colors; lots of festive red garments for those who had attended Pentecost worship earlier that day; bright, geometric patterned headscarves, tunics and skirts; firefighters and sheriff’s deputies clearing the way. Their faces were black, white and brown, old and young. Some held hands as they crossed the road. Others waved to friends they hadn’t seen since before the pandemic.

Perhaps the onlookers wondered what kind of person merited such an impressive congregation for their parting rites. No one could have guessed the answer to that question.

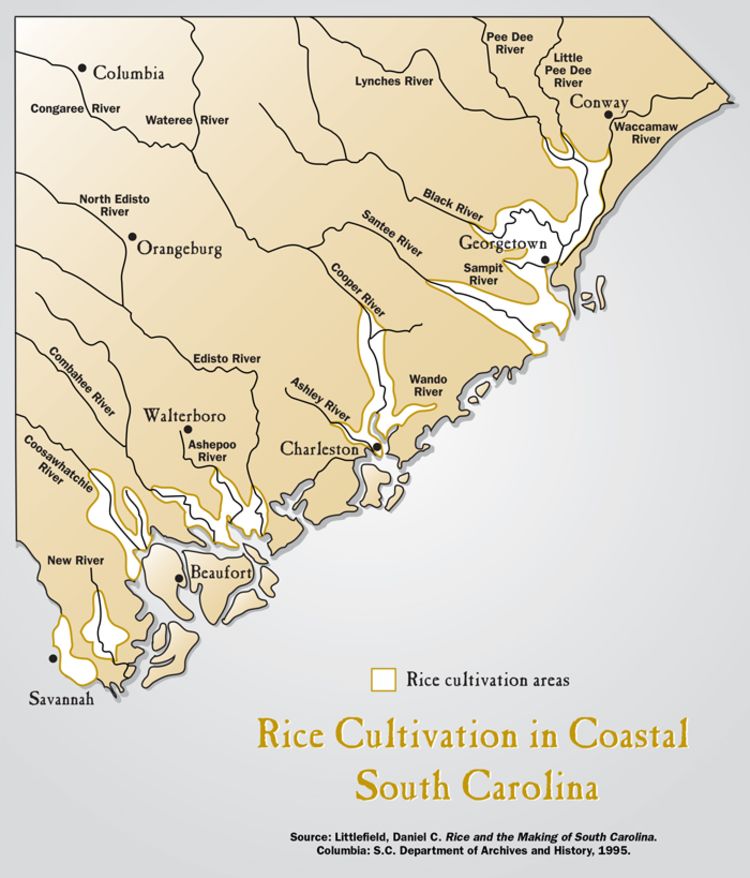

Under the tent stood a dignified wooden casket beside its new resting place. It was covered with lilies, predictably. But inside the box were the remains of not one, but 22 human beings whose living bodies were enslaved in the rice-fields of the Waccamaw Neck and whose bones had been removed from their resting place when a bulldozer uncovered them during the construction of a luxury home in 2006.

For Gullah-Geechee activist and poet Zenobia Harper, it was a day for questions. “What could we really do—what really needs to be done to pay proper respects to the people who used those bones? I wondered to myself if the people that were gathered there really understood the gravity of what was happening. How many people understood the deepness of that day?”

It was also a day for poetry and prayer. Harper recited her Gullah-language poem written especially for the occasion, “To De Bone.”

“It was almost like they were here, laying above the ground, as a reminder that we have to do more digging. We have to go deeper,” not to disturb remains, but to disturb the complacent ways we tell the stories of our nation and region.

“I pray,” she stated, “that this is the last time your bones are moved for other people’s desires and progress. I pray that this time your weary bones find peace and take their final rest.”

It was an honest prayer. The remains were likely moved for the first time in the 1970s, when the former lands of Hagley Plantation were sectioned off into high-end resort housing. Manigault Funeral Home of nearby Georgetown, South Carolina, was apparently tasked with moving them to the site disturbed again by more development in 2006, but any records were lost when the business failed. By that time, however, a new County Coroner, Kenny Johnson, and his lieutenant, Chase Ridgeway, took responsibility for the remains.

They were taken to the University of South Carolina for forensic investigation, which produced a full accounting and description of the remains. In analyzing the skeletons, including DNA testing, investigators established that these were people of African and Middle Eastern descent whose lives were characterized by hard labor, malnutrition, and disease. Researchers were even able to identify a community of descendants based in the Marysville area of the Waccamaw Neck. But none of the descendants they contacted wanted to be involved. After the study was concluded, the bones remained in a county vault until that Pentecost afternoon when Harper, area clergy and churchgoers, civic officials, musicians, and citizens gathered to lay them to rest.

Harper later said of those bones, “It was almost like they were here, laying above the ground, as a reminder that we have to do more digging. We have to go deeper,” not to disturb remains, but to disturb the complacent ways we tell the stories of our nation and region.

Such stories have more than one beginning. For Georgetown County Administrator Angela Christian, it began when Ridgeway and Johnson—Ridgeway had just been elected as County Coroner after Johnson’s retirement—requested a meeting. Christian herself was still a newcomer and knew nothing of the remains. She had expected an ordinary discussion about the coroner transition. What they told her came as a surprise, but all were agreed that it was time to give the remains an appropriate reinterment.

“I understood that any ceremonies could be very sensitive to the community at large, and I didn’t want to get it wrong.”

Gullah-Geechee activist and poet Zenobia Harper recites her original piece, “To De Bone.”

Gullah-Geechee activist and poet Zenobia Harper recites her original piece, “To De Bone.”

HCFM Senior Warden Kris Southard greets the Rev. Johnny Ford of House of God Church, which neighbors the parish.

HCFM Senior Warden Kris Southard greets the Rev. Johnny Ford of House of God Church, which neighbors the parish.

She contacted Bishop John Smith Jr. of Greater Bibleway Church of Georgetown and the Rev. Carl Anderson, pastor of Greater St. Stephen A.M.E. Church and member of the South Carolina House of Representatives. After initial discussions, it became clear that this was an entirely new kind of undertaking for Georgetown County.

“I just started by talking to folks. Is anything written down? Is there a how-to somewhere? How do we do this? There was no roadmap.”

Christian contacted a few Charleston citizens who had been involved in a similar project, but the Georgetown County case was different in an important respect.

“The bones had been comingled, and the question I kept returning to was, how do we honor their remains in a dignified manner? We understood that this needed to be a community project. It wasn’t just one set of folks that were impacted by these unnamed rice planters and their families.”

From left to right: [standing] Georgetown County Administrator Angela Christian; State Representative and Pastor, the Rev. Carl Anderson; County Coroner Chase Ridgeway; [seated] Bishop John Smith, Jr.; the Very Rev. Wil Keith, T’09

From left to right: [standing] Georgetown County Administrator Angela Christian; State Representative and Pastor, the Rev. Carl Anderson; County Coroner Chase Ridgeway; [seated] Bishop John Smith, Jr.; the Very Rev. Wil Keith, T’09

At the suggestion of Ridgeway, Christian also contacted the Very Rev. Wil Keith, T’09, rector of Holy Cross Faith Memorial (HCFM). Though Christian’s initial conversations were with Black church leaders, she agreed that HCFM and its pastor made some sense to be hosts of the ceremony. Anderson and Smith both pastored churches in mainland Georgetown County. “But,” said Christian, “we felt it was important that these folks be interred where they came from, on the Waccamaw Neck. We felt it was important that they return to that space.”

Aside from geography, it was historically appropriate as well. HCFM was born from the merging of two Black mission congregations at the end of the 19th-century and traces its roots to the many slave chapels that existed on the Waccamaw Neck until the end of the Civil War. It was a majority African American congregation until about the turn of the millennium, and its historic cemetery contains the remains of formerly enslaved people.

In fact, the parish’s story exemplifies the historical contours of the wider African American community in the Pawleys Island area. The Black population has decreased locally since the time of the Great Migration. Some left for work and educational opportunities available on the mainland or in northern cities. Others moved more recently, displaced by increasing luxury development. Some, of course, are still here in town and in the parish, stewarding the civic and church institutions built and sustained by their ancestors.

But the fact remains that, in 2021, HCFM is a majority-white congregation with a white rector, and Christian understood the sensitivity needed. “But let me tell you about breakfast. Before this project, Bishop Smith and Reverend Anderson did not know Father Wil. So, I invited all of them to breakfast at my expense at the Ball and Cue.”

The Ball and Cue is like any other small-town diner in the Lowcountry. Florescent lights hang from drop-down ceilings, illuminating plates of eggs, barbecue hash, shrimp and grits. On the tables little packs of sweetener stand next to bottles of Texas Pete and pancake syrup. Waitresses call diners “Hon,” whatever their race or age or class. Local little league teams go there for victory milkshakes, surrounded by photos, jerseys, helmets, and banners celebrating the Georgetown High Bulldogs.

“I thought Father Wil coming into our group would make us practice what we preach,” said Christian. “That this has to be inclusive, that it has to be a common goal for all of us, to get it done right. You get one shot at this. We took our time to involve all different kinds of people who recognized the importance of this event to the entire community, not just to one particular group or another.”

Keith was grateful to meet new colleagues on the project. “By the way, it was fun. It was a really fun group to work with. Here we were, this group of clergy and community leaders, belly-laughing together over biscuits while trying to serve our neighbors. There is great joy here, too. We were almost like a bereaved family, gathered to plan the funeral.”

Christian seems to have accomplished her goal at breakfast. Before long the pastors acted less like colleagues and more like friends, developing not only a sense of professional trust in this burgeoning partnership, but a feeling of camaraderie and mutual understanding.

“In times like these, when there is so much to divide us, we really need to identify those opportunities to unite us.”

Months later, as Christian surveyed the crowd that Pentecost afternoon, watching all their planning come to fruition, she couldn’t help but be moved by what she saw. “We drew from all corners of the community. It wasn’t just exclusive to Pawleys Island. There were people of all walks of life from Georgetown County. Folks came from Charleston, Myrtle Beach. Black, white, young, old, in between—it affected all groups of people, to be part of something they will talk about 20 years from now—how important it was to be there and to bear witness.”

Christian’s advice to other civic and church leaders? “Take your time to learn as much as you can. There are lots of different opinions about how something like this should be done and who should be involved, and you want to do the best you can. Over time, there will no doubt come some standards about how to do this process. But for now, do your due diligence. In times like these, when there is so much to divide us, we really need to identify those opportunities to unite us. No matter how painful some of our history may be, it’s what makes this community what it is today.”

“There is a danger of the heritage of this place—the good and the bad—being erased, for the sake of comfort, for the sake of profit.”

She sums up her counsel to leaders in the intersection between church and state in two words: “Be bridgebuilders.”

Bridgebuilding comes naturally to Keith, known to parishioners and Pawleys Island locals alike as Father Wil. Whether he’s jawing in garages over his recent pet project (restoring a ‘91 Land Rover Defender), coaching girls’ soccer, or serving on the front lines of the Midway Fire Department in his role as their chaplain, Keith’s ministry combines the sincerity and affability of the village parson with the adventurous goofiness of the camp counselor who, quite consciously, isn’t all that ready to grow up just yet. It is this nimble spirit, plus his decade’s worth of involvement in the community, that allows him to form relationships with everyone from elected officials and millionaire retirees to overworked landscapers, cover band guitarists, and grouchy fishermen.

Keith stands next to his 1991 Land Rover.

Keith stands next to his 1991 Land Rover.

Keith was well-placed, then, to collaborate. Shortly before planning commenced on the reinterment ceremony, Keith had participated in a quiet effort to expand affordable housing on the Waccamaw Neck. While that initiative ultimately failed, it meant that Keith and Christian already had a relationship built on openness and trust. They also recognized in each other a desire to do right by the poor and marginalized in their local community.

“As this area becomes more and more identified with upper-middle-class and upper-class retirement,” said Keith, “there is a danger of the heritage of this place—the good and the bad—being erased, for the sake of comfort, for the sake of profit. It is important to continue having this story out in front, unignorable, so that people who are here continue to grow in their understanding of who they are, their place in the world, and their responsibility to their neighbor.”

While every individual experienced the ceremony in their own way, they also shared in the same prayers, poetry, songs, conversations, and stories. As Keith recounts, “All stories are worth being told and heard. All stories can teach us how to live in this world and lead us into life in the next. They may be forgotten or glossed over or shelved because of how they could affect real estate prices, because they can be painful to hear. We avoid pain every chance we get, but we grow through it, and it is not an unendurable suffering for white folks to understand this story.”

Where church and state had collaborated for so much evil in the institutions of slavery and segregation, there is now an opportunity to collaborate for good.

For Keith, the day brought a new realization. Where church and state had collaborated for so much evil in the institutions of slavery and segregation, there is now an opportunity to collaborate for good, whether it is in the construction of a monument to those souls whose names are forgotten, or in the construction of affordable housing, better transit, and a more equitable society.

Personally, said Keith, “it was a deep honor and privilege to get a second chance to honor the ones we reinterred. I can’t assume their first burial was attended by elected officials, the press, community leaders, and a whole wide swathe of the church. It was a second chance—we all need those.”