Grappling with the Prince of Slavers

A Sewanee history professor’s research informs the Bank of England’s efforts to examine its history and the role it played in the transatlantic slave trade.

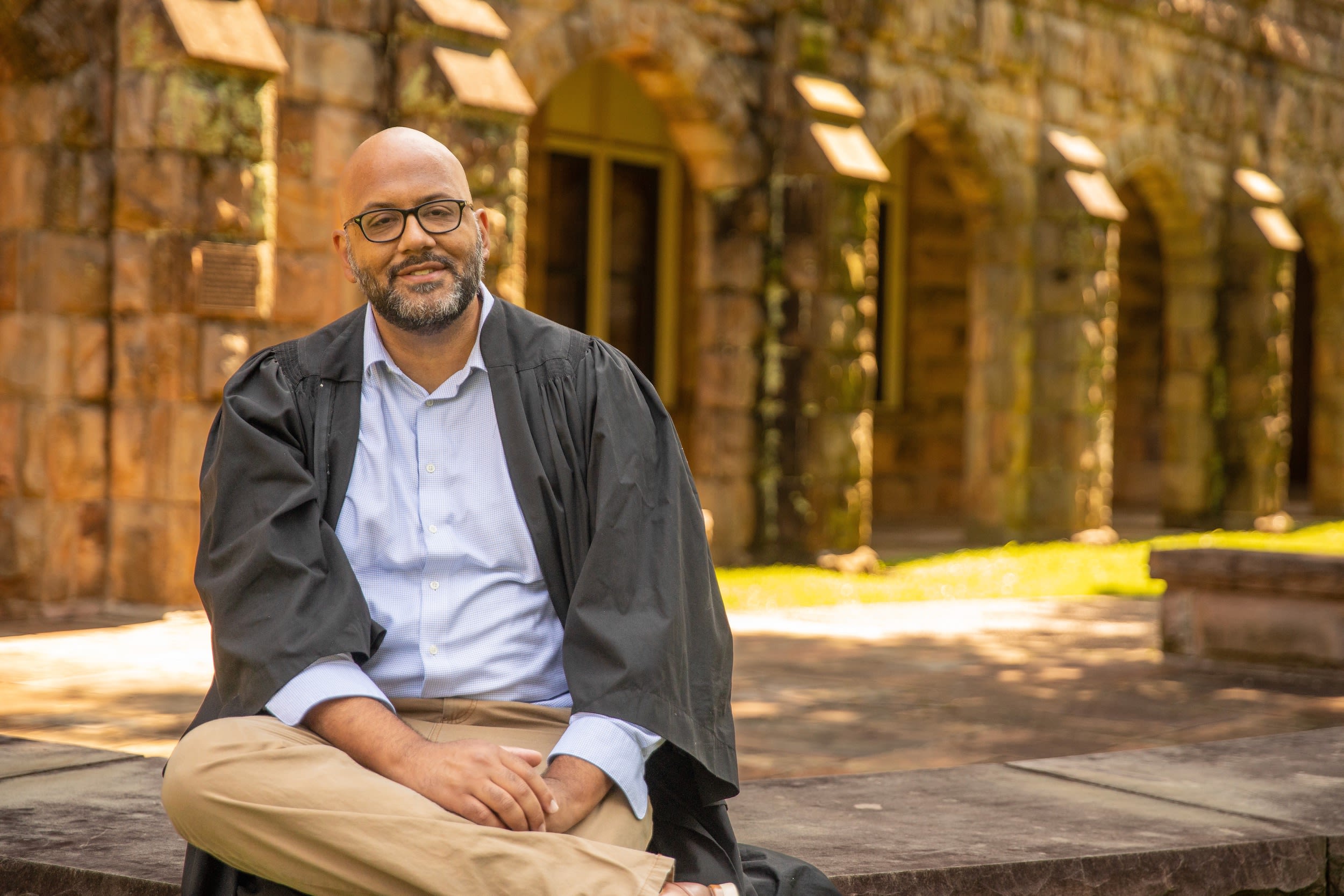

“HISTORY has taken me all kinds of places,” says Matthew Mitchell. In June of this year, it took him to London, England. After tea with a colleague at the British Library, Mitchell hailed a cab, telling the driver, “Bank of England, please.” Upon entering the bank’s museum, Mitchell picked up a guide to the current exhibition, Slavery & the Bank. Flipping through the pamphlet, his eyes landed on a familiar name cited within its pages: his own.

The sequence of events that led the Sewanee associate professor of history to that moment began two years earlier. In the wake of George Floyd’s murder in May 2020 and subsequent global protests against racism and police brutality, the Bank of England, like many institutions on both sides of the Atlantic, embarked on a project to examine its own history and the role it played in the transatlantic slave trade. The resulting exhibition in the Bank of England Museum, which will run through April 2023, includes a section on former governor of the bank and Member of Parliament Humphry Morice—an influential independent slave trader and the subject of Mitchell’s 2020 book The Prince of Slavers.

With his years of research suddenly lent new urgency by a remarkable confluence of world events, Mitchell would ultimately find himself on stage at the Bank of England Museum giving a public talk on Morice’s life and legacy. Proving the ongoing value of mining the past to better understand our present, Mitchell’s deep dive into and conscious reframing of one man’s life story was more than an exercise in biography. For Mitchell, it represented an opportunity to engage with larger questions about what it means to look to the past, the stories we choose to tell about it, and who, exactly, gets to do the telling.

Accidental Historian

MITCHELL did not originally intend to become a historian. A business major as an undergraduate student, he added a second major in history during his senior year after noticing how much he enjoyed those classes. One post-college year in the business world confirmed for Mitchell that his initial career interest was no longer his passion. A master’s in history quickly followed, and after that an opportunity to teach history at a community college.

It was that teaching experience that sparked Mitchell’s interest in conducting research. To be suitably knowledgeable about a given topic in class, he would consult existing literature and articles on it. “You start with one,” he explains, “and it may answer some of your questions, but it might also raise some others. So, then you go and find the next thing to read to get those new answers, and then see what newer questions you now have. And so on.” Eventually, though, he found himself in the predicament of figuring out what to do if the book on the question he was trying to answer did not exist. “I realized,” he says, “that I would have to go and write it.”

While pursuing a Ph.D. at the University of Pennsylvania, Mitchell began researching the Royal African Company, an English mercantile company formed in the 17th century for the purpose of trade along the western coast of Africa. Combining his business background with his new interests as an historian, he intended to lay the groundwork for a book-length, updated history of the company, as the only previous such treatment had been published in 1957. So much had changed over the intervening decades about how scholars approach study of the transatlantic slave trade—“The field of African history as we know it today didn’t exist yet,” notes Mitchell—that the time was right to revisit the company’s history in depth.

To do that work properly and more fully evaluate the company’s business activities, Mitchell felt that he would need to better understand a contemporaneous economic competitor within the slave trade as a point of comparison. Enter Humphry Morice.

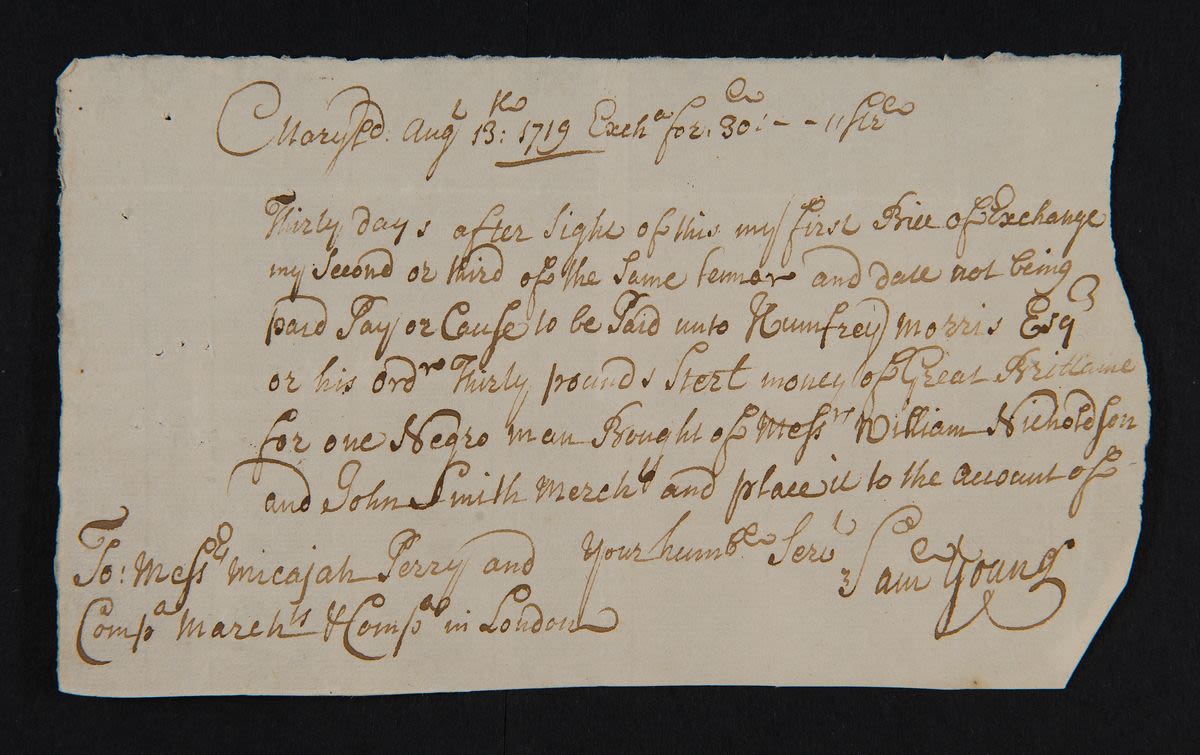

In 1719, Maryland slave owner Samuel Young drafted this bill of exchange worth £30 to purchase an enslaved African man from Humphry Morice. The bill was cashed in at the Bank of England.

In 1719, Maryland slave owner Samuel Young drafted this bill of exchange worth £30 to purchase an enslaved African man from Humphry Morice. The bill was cashed in at the Bank of England.

The Prince of Slavers

IN 2014, Mitchell began poring over Morice’s ample surviving records, spending hours upon hours seated at duPont Library’s microfilm reader and a week with additional original documents in the Bank of England’s own archives. The portrait that emerged of the man was a striking one. “Among the other things he was,” says Mitchell, “Morice was certainly an interesting guy.”

A connected political figure and leader within the Bank of England, Morice quickly amassed significant wealth as an independent slave trader thanks to innovations that allowed him to outperform the previously dominant Royal African Company. He lived long enough to see a new generation of competitors outmaneuver him, leaving him to see his profits turn to ever-increasing—and highly documented—debt. In a state of desperation, he embezzled from the bank and forged bills of exchange (an equivalent to today’s checks) in a final attempt to stave off poverty before an ignominious death—officially recorded as due to gout, though rumors persisted that he died by suicide.

The book that resulted from Mitchell’s extensive research, The Prince of Slavers, was the first to examine Morice and his business practices at such length. Over the years of preparation and writing, Mitchell had no way of knowing that the book’s early 2020 publication would coincide with a cultural moment that would lend his work new relevance, nor could he have foreseen that the Bank of England’s subsequent reckoning with its history would generate an exhibition with a section dedicated to his central subject.

By this time, Mitchell had emerged as a leading scholar on Morice and his legacy. In addition to publishing The Prince of Slavers, Mitchell had been tasked with writing an updated entry on Morice in The Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, a biographical reference for notable figures in British history that has been published since 1885. As the Bank of England Museum’s curators assembled the Slavery & the Bank exhibition, Mitchell’s work helped to inform the Morice section. After opening the exhibition in the spring, the museum invited Mitchell to give a talk on Morice and his legacy, allowing Mitchell the opportunity to present a new history of the man at the site of an institution that had given him legitimacy.

Lives on a Ledger

THROUGH the process of preparing his book and later talk, Mitchell was always cognizant of the weight of the material. “I’m studying, in essence, how good these men like Morice were at doing something evil—profiting from the trafficking of human beings,” says Mitchell.

Inherent to Mitchell’s work is a tension that arises from the application of an economic lens to the study of the slave trade. Whereas another area of scholarship seeks to recover as much as possible of the experience of enslavement and the perspective of the enslaved, Mitchell’s analysis centers on understanding the conditions of slavery as rooted in and sustained by a profit motive. In Mitchell’s view, both lines of inquiry must ultimately connect, as we need to understand that motive in order to better explain the brutal system that it spawned. Yet the nature of Mitchell’s research requires that he direct significant attention to the slavers.

For Mitchell, that means approaching the topic with a conscious drive to reconsider and reframe inherited narratives about Morice and about the transatlantic slave trade. In practice, that looks like consistently acknowledging the long history of resistance by enslaved people, who fought their commodification at every turn. And it also involves intentional recontextualization of prominent historical figures like Morice, who had previously been celebrated for shrewd business acumen without much heed paid to the associated human cost of his profit ventures. “Given what we know now,” asks Mitchell, "does he still meet our standards of who and what should be celebrated?”

Mitchell has taken great care to tell Morice’s story without lionizing the man. On a linguistic level, Mitchell directly and repeatedly calls Morice’s business what it was, without any softening euphemism—the trafficking of enslaved human beings—to reclaim the humanity that the enslaved were relentlessly denied. Rather than frame Morice’s story as that of a great entrepreneur, he refers to Morice by other equally fitting terms such as “fraudster” and “embezzler.”

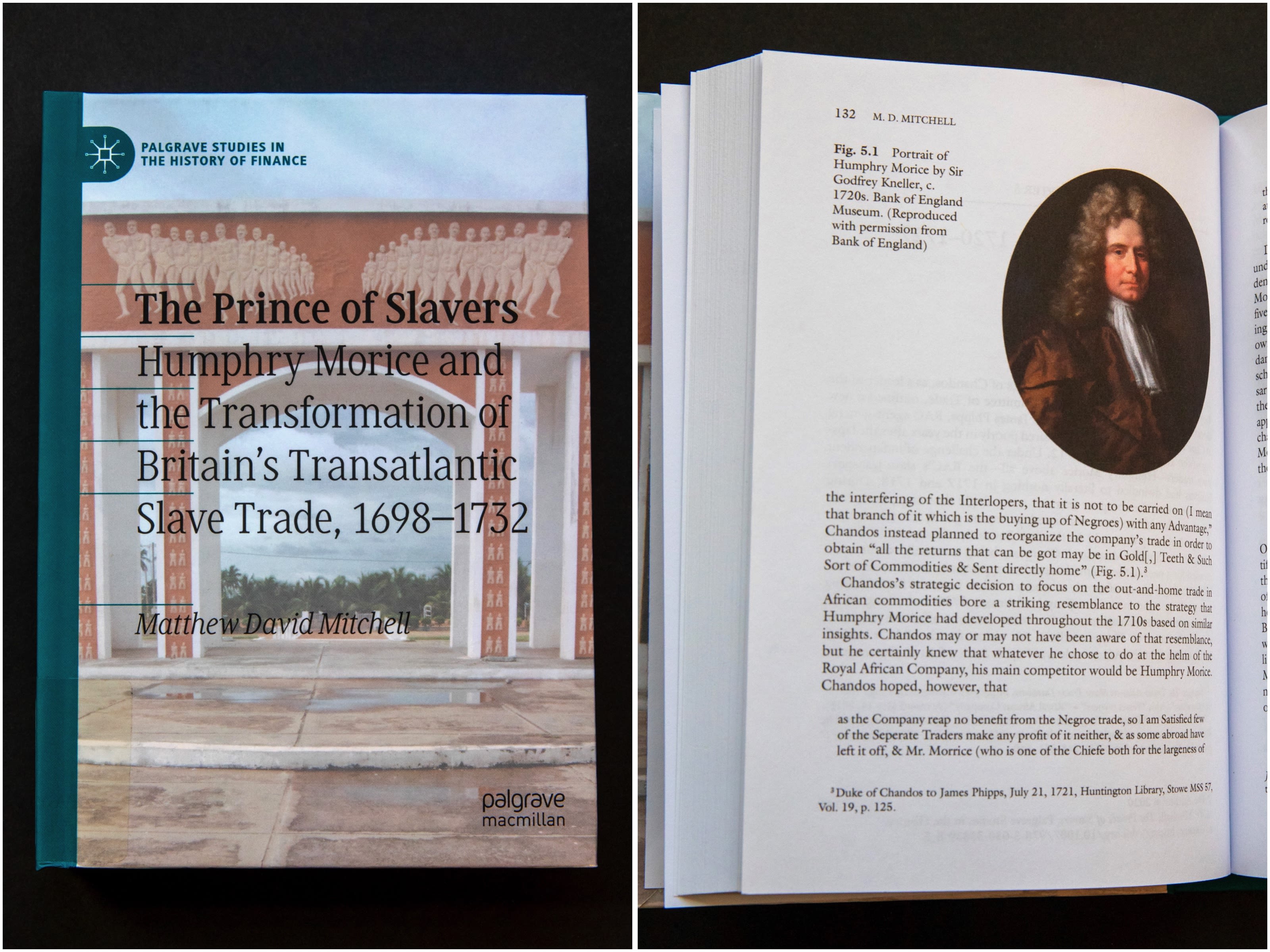

Perhaps most significant are the choices Mitchell made with respect to the artwork included in The Prince of Slavers. A color portrait of Morice appears only on the inside of the book and not, as it might for a traditional biography, on the cover. Instead, the cover image is that of La Porte du Non-Retour (The Door of No Return), a monument to the more than one million enslaved Africans deported from the port of Ouidah in what we know today as Benin.

Mitchell's Prince of Slavers features a monument to enslaved Africans on its cover, not an image of Morice, which appears only inside the book.

Mitchell's Prince of Slavers features a monument to enslaved Africans on its cover, not an image of Morice, which appears only inside the book.

In one especially stunning moment during his talk at the Bank of England, Mitchell displayed one of the documents he encountered in the bank’s own archives. It contained records of death for several enslaved people alongside a summary of monetary loss, effectively putting, in Mitchell’s words, “lives on a ledger.” This document, he explained, shows us what those in power deemed most important to know about the people they enslaved.

For the slavers, what was worth recording for history was not the enslaved people’s names, family histories, or any personal information about who they were as people; it was their sex, age, and date of death—so that the slavers could cash in on insurance policies and, even in death, continue to profit from the subjugation of other humans.

While he engages with documents like these as part of his professional pursuits, the material also has a personal resonance for Mitchell. “I am not someone who has traced their family lineage all the way back to Africa,” he reflects, “but it’s possible–unlikely, but possible–that my ancestors were on Morice’s ships.” Under Morice’s power, they could have been subject to being stripped of their humanity and identities, reduced to numbers and figures on documents like the one Mitchell presented. Now, Mitchell notes, Morice’s surviving documents and letters are in the hands of scholars like himself—scholars who now have the power to tell a new and different story.

“Stories are so important,” says Mitchell. “They are how we come to know the world and understand the people in it.” After centuries of narrow storytelling about the transatlantic slave trade and its legacy, he says, “Now I’m the one getting to tell this story.”