Designing a Just Society

Sewanee Assistant Professor of Psychology Katy Morgan’s pioneering community design program empowers students to transform the places they live by conceptualizing stronger, more resilient neighborhoods.

Having a conversation with Assistant Professor of Psychology Katy Morgan is like jumping on a moving merry-go-round—take a running leap and hang on. She’s sparkling water, not still; a shooting star, not a fixed constellation. Mention a book—for example, Hot, Hot Chicken: a Nashville Story by Rachel Louise Martin—and before your sentence has ended, she has found the book online, ordered it, and received the confirmation email from the online store.

Hot, Hot Chicken is no random example. A book about urban design wrapped in a story about the spicy barbecue chicken that Nashville has claimed as a signature dish, it explores a topic that is dear to Morgan’s heart. She is part of a small but growing subdiscipline of psychology called community psychology. The idea behind community psychology is that it is not enough to understand the pathologies, the therapies, the chemistry, and the learned behaviors informing the human condition; it is also important to understand the social structures and the built environment at play in shaping human behavior, health, and efficacy—not to mention the role of a signature food.

In her graduate program at Vanderbilt and beyond, Morgan has been immersed in thinking about community design, partnering with the Civic Design Center in Nashville to build an educational program called “Design Your Neighborhood” that has engaged teachers and students in Nashville, Chattanooga, and in the outdoor recreation gateway community of Oneida, Tennessee.

“The built environment has a huge effect on human well-being,” she says. “Design Your Neighborhood works in both affluent neighborhoods and neighborhoods that are less so, including neighborhoods undergoing rapid transformation through gentrification. One finding is that students of color have lower attachment to place than white students,” she says, explaining that “displacement and gentrification have a big negative impact on young people’s sense of community and connection to place.”

By engaging students in thinking about what they want for their communities, Morgan and Melody Gibson, education director at the Civic Design Center, were hoping to unlock the potential of students. “Design Your Neighborhood enhances students' feelings of efficacy and helps them understand at least a pathway to building a just society.”

Nashville middle school students participating in the Design Your Neighborhood program trace sites for sidewalk and crosswalk extensions over a map of their school community.

Nashville middle school students participating in the Design Your Neighborhood program trace sites for sidewalk and crosswalk extensions over a map of their school community.

A little over a decade ago, Morgan made her first visit to Sewanee as a college student at Millsaps. It was a football weekend, and Morgan came up for the game, but what she really wanted to do was hike the trails and see the campus. “Sewanee was the most beautiful campus I had ever seen,” she says. That weekend, however, she was actually on a hike that was leading her ever closer to what she believed was her life’s calling—becoming a public-school English teacher.

“I went to Millsaps for teaching. I wanted to be an English teacher, and after I graduated, I got a job in Jackson teaching 10th- to 12th-grade English. When you’re teaching literature and writing, you are working with critical analysis and critical thinking, and as I worked with students on their writing and literary analysis, it just became really clear that in Jackson we were in an unjust system. The English classroom creates space for critiquing unjust systems, but there are not a lot of resources available to high school teachers to help move their students from analysis to action. The schools were chronically underfunded. And there were a lot of unknowns for me about what my students were facing outside the four walls of the classroom. There was one incident where a student literally died in a traffic accident because the car in which he was riding hit a pothole. That accident encapsulated what I was feeling about how lack of infrastructure was connected to racism and how racism plays out in the built environment.”

Eager to move past critical thinking and analysis to action, Morgan applied for and enrolled in a stand-alone master’s program at Vanderbilt’s Peabody College in Community Development and Action. It is a two-year graduate program through the Department of Human and Organizational Development that aims to attract students “committed to learning how to create positive, community-level change in a collaborative and participatory way.”

During the program, Morgan’s career took a turn when the executive director of the Civic Design Center, Gary Gaston, was in one of her classes. Gaston was an architect and fully immersed in that professional world, but he, like Morgan, wanted to learn more about community development and saw the Peabody program as a way of doing that. The Civic Design Center, which had been at the forefront of participatory urban design in Nashville since 1995, had also just hired Melody Gibson as education director, and a partnership was formed.

“In 2017, we developed a small summer program for high school students, on which I worked as an evaluator,” Morgan says. “It was a real crash course on what was happening on the ground in Nashville. The work was really impactful and we began to ask how we could get this kind of experience for everyone, especially students who were experiencing lack of access to transportation and the effects of gentrification on their communities.”

The team began working on the curriculum for middle school and, in 2018-19, they did an in-service teacher training, and 30 teachers got involved in delivering the curriculum in Nashville Metro Public Schools.

After earning a master’s degree, Morgan was hooked on community development and enrolled in the doctoral program in the Department of Human and Organizational Development in Community Research and Action and continued working on the Design Your Neighborhood program. “I just became convinced that I wanted to see this inquiry through to learn more about that work.” The Department of Human and Organizational Development at Peabody is a deeply interdisciplinary program that includes social scientists, psychologists, and public health practitioners. Morgan’s work involved many of those perspectives as she continued to work on Design Your Neighborhood, helping extend the program to a second city, Chattanooga, and the more rural setting of Oneida.

When Sewanee advertised a tenure-track position aimed at scholars whose work supported the public good, Morgan applied and was hired, even though she had not yet completed her dissertation. “I entered the job market a year early specifically for the position at Sewanee,” she says, noting that her first visit to Sewanee as a college student made the prospect even more attractive.

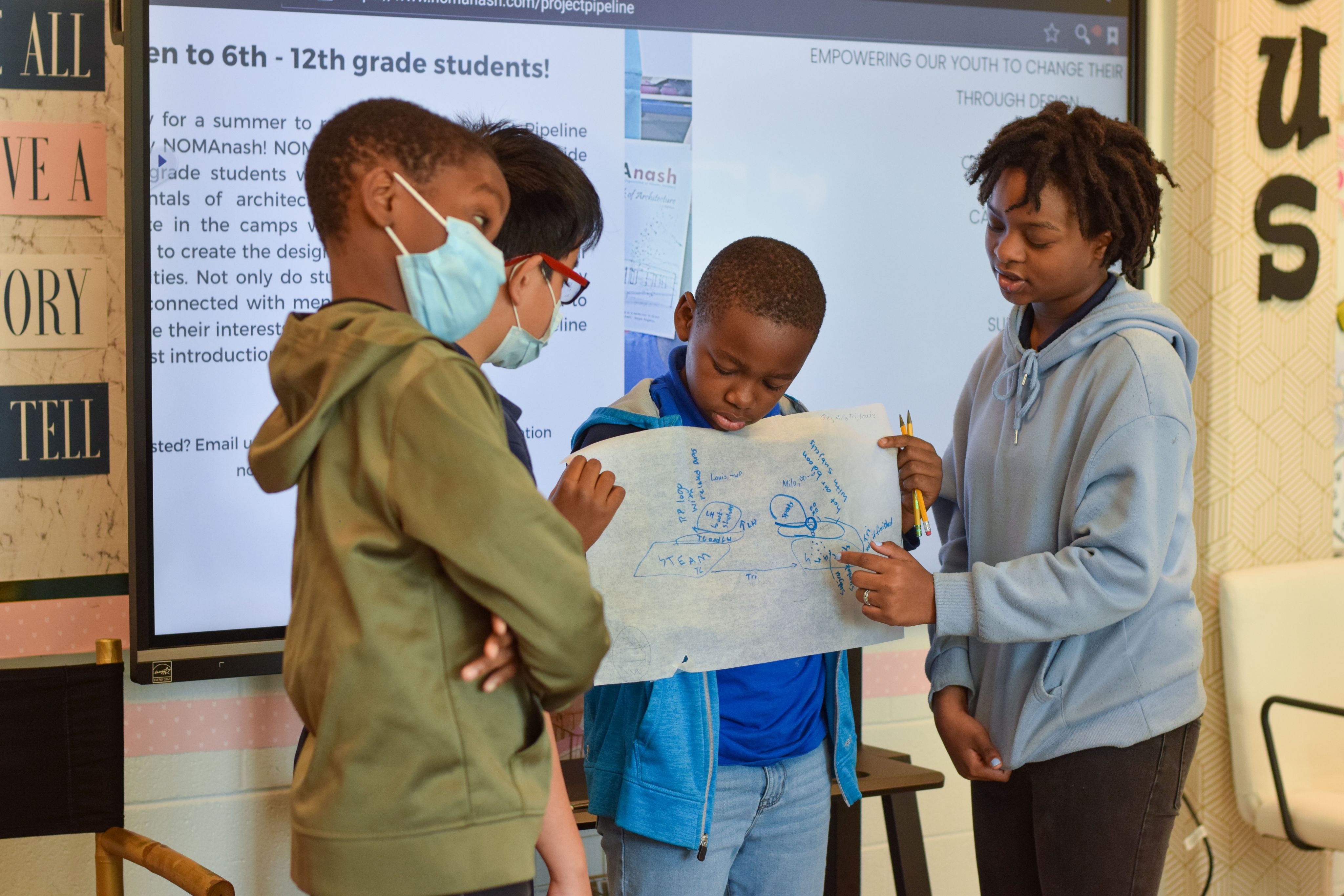

Nashville middle school students present their in-progress design plan to their classmates, teachers, and community volunteers for feedback.

Nashville middle school students present their in-progress design plan to their classmates, teachers, and community volunteers for feedback.

While Morgan is the first member of the Psychology Department at Sewanee to have come out of a formal program of community psychology, she fits in a department that has been advancing the subdiscipline’s ideas for some time. For the past 10 years, Karen Yu and Linda Mayes have taught a course, Child, Family, and Community Development in Southern Appalachia, that involves local educators and leaders in teaching Sewanee students about how the individual, the family, and the community can work together to build human thriving. Kate Cammack has done great work on substance abuse, working with the Safe Schools Coalition. Helen Bateman has looked at thriving in local schools, and Al Bardi has been investigating the Sewanee student experience. Sherry Hamby has been doing work that has a focus on public good, working with local organizations like the Grundy County Health Council and the South Cumberland Community Fund as well as her own research into anti-violence and trauma.

In fact, in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, members of the Psychology Department took the notion on as an organizing principle that they would have as their core mission, what they called “psychology for the public good.”

“When I learned about the position opening at Sewanee as a Vanderbilt doctoral student, I was really energized,” says Morgan. “I could see myself contributing to that kind of exciting work. Every single person in the department has something to offer that vision. No one is locking themselves up in a lab and ignoring the public good.”

With the dissertation behind her, Morgan is ready to immerse herself in the kind of action research that is behind Design Your Neighborhood. The University has provided startup funding that will allow her to implement some of the program in local schools, and she is working with community partners to secure additional external funding for a project that will combine community design by landscape architects and a school-based program, where youth are involved in visioning for the community.

One of the principal activities of Design Your Neighborhood is a demonstration exhibition at the conclusion of the program, at which students present their ideas for the community, and Morgan thinks the school-based program will work particularly well on the South Cumberland Plateau. “When we did the design fair in Oneida, the whole community turned out. People wanted to support their children and their neighbors’ children, and I think the same kind of effect can happen in our community here on the Plateau.”

Morgan has observed that students in rural areas have a bit more access to social power than students in urban areas. “If you are a student in a local school in a rural area, your uncle or your neighbor or someone you know is likely to be a person with some influence on local policy, whereas in an urban area, the power structures are much more remote for the average person.”

Many people on the South Cumberland Plateau believe that the area is headed for a once-in-a-generation opportunity to make positive changes in economic and community development. The Tennessee Department of Environment and Conservation is investing millions of dollars in local parks. The Mountain Goat Trail, a multimodal rails-to-trails project is gaining momentum, and new state funding promises the project might be complete in the foreseeable future.

“We know change is coming,” Grundy County Mayor Michael Brady often says in public meetings. “We want to be able to shape that change instead of just letting it happen to us.” Morgan and her Civic Design Center partners are ready to lend their expertise and experience in tapping the genius of the community to envision a brighter future. Design Your Neighborhood is a key part of that vision because it speaks to the literal future as embodied in its young people. Can the area prepare itself to forestall brain drain, to build in reasons for talent to stay on the Plateau as teens turn to adulthood? Morgan is prepared to help the community design just that outcome.