Creating the COVID Classroom

When it came to equipping faculty to teach through a pandemic, Sewanee had a 25-year-old secret weapon that was purpose-built for the challenge.

Just before Christmas in 2019, when droplets of novel coronavirus were first spreading through American subways, cruise ships, and office complexes, Sherwood Ebey, professor emeritus of mathematics, passed away peacefully in his home in Macon, Georgia. Ebey could not have known then the impact his career would have on Sewanee in the coming months, as the University responded academically to a global pandemic. With a fall semester that challenged professors to implement new teaching strategies, an important foundation for meeting the challenge had been laid almost exactly 25 years earlier in December 1995, when Ebey presented in a faculty meeting a report on a newly created academic asset, the Center for Teaching.

In that initial report, Ebey laid out guiding principles for the Center: voluntary participation by faculty, the leveraging of University resources (technological and human) to support teaching, and an experimental approach to and a repository of information about teaching. He also outlined some potential activities, including workshops on teaching, orientation of new faculty, conversations about teaching among faculty, and, interestingly, “playing a leadership role in the development of electronic classrooms and the use of electronic technology in teaching at Sewanee.”

“The Center for Teaching was really innovative when it started in the 1990s” says Betsy Sandlin, who was co-director of the Center from 2014 until her appointment as associate dean for inclusion and faculty development in 2019. “But over the years, other colleges developed similar centers, and some of them passed us by in terms of resources.” In 2014, Sandlin and Deon Miles became co-directors after a survey of other centers for teaching across the Southeast was conducted by a team of Sewanee faculty and staff. “We did a lot of designing, thinking, and imagining, and when we presented our recommendations to the faculty for a revitalization of the Center, we received a standing ovation,” says Sandlin. “I think that is the only standing ovation I have ever seen in a Sewanee faculty meeting.”

Over the past five years, the Center for Teaching has enjoyed a renaissance, with an overhaul of systems and leadership that passed from Sandlin, Miles, and Interim Director Rae Manacsa, to Emily Puckette, professor of mathematics, Jordan Troisi, associate professor of psychology (now at Colby College), and Mark Hopwood, associate professor of philosophy. Along the way, an energized advisory board worked with the co-directors to build a learning community of faculty. And as the Center for Teaching has deployed over the last year, helping faculty to prepare for strikingly different modes of instruction during a global pandemic, what is equally striking is how true the CfT has always been to the principles established at its founding by Ebey.

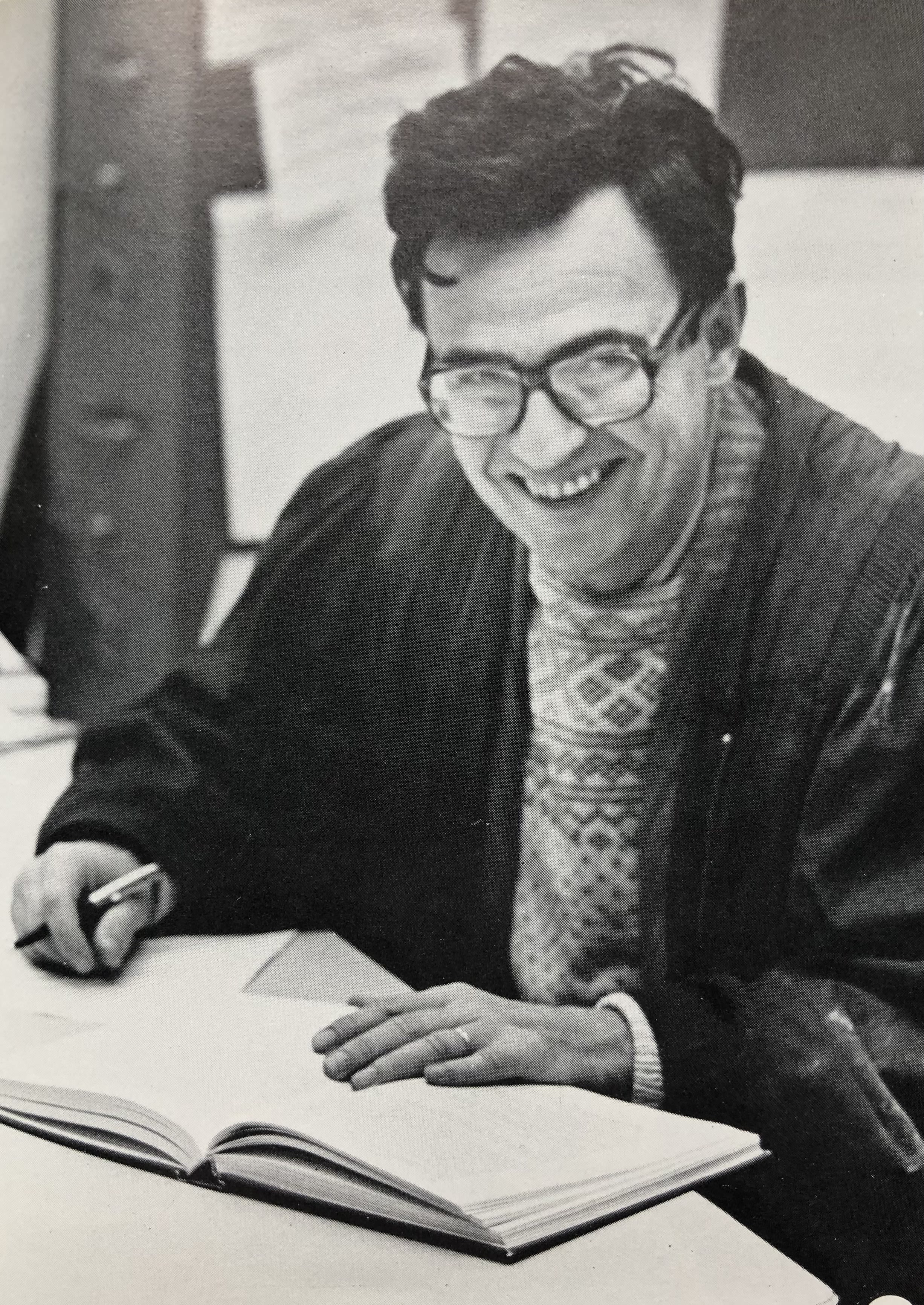

Math Professor Sherwood Ebey founded Sewanee's Center for Teaching in 1995 and envisioned it "playing a leadership role in the development of electronic classrooms" at Sewanee.

Math Professor Sherwood Ebey founded Sewanee's Center for Teaching in 1995 and envisioned it "playing a leadership role in the development of electronic classrooms" at Sewanee.

PRINCIPLE #1:

Voluntary Participation and Conversations Between Professors

For Sherwood Ebey, the Center for Teaching was “really about faculty being supportive of one another and honing their craft,” says Richard O’Connor, the director of CfT in the 2000s. That foundation of collegiality, nurtured over decades, helped in spring 2020 when the entire faculty had to pivot to remote learning.

“Last spring, all of a sudden all these professors can’t do what they normally do,” says Miles. “But we still have to get through. Really, it’s the combination of the Center for Teaching and Betsy Sandlin and Adam Hawkins [now the University’s instructional designer] who helped faculty prepare for new modes like video conferencing, Zoom, being more flexible. Then at the end of the semester, they didn’t stop. They spent the summer developing new tools and helping faculty get ready for the coming semester.”

Emily Puckette, professor of mathematics and co-director of CfT remembers it this way: “In March—on my birthday, as a matter of fact—John McCardell made the determination that we were going to finish the semester remotely. I immediately started thinking about my own classes, scouring the Internet for best practices. And then, very soon thereafter, Adam Hawkins, Jordan Troisi, and I began developing faculty training sessions, drawing on resources from all over the country.” Their work was a kind of middle-distance race, moving fast to prepare faculty and address faculty concerns but keeping their eye on a longer future, in a summer where Sewanee was transitioning not only to new teaching modes but a new course management system for delivering online content.

Now in spring 2021, with the first semester of COVID classrooms behind them, the Center for Teaching continues to deliver content and conversations. A weekly email from Puckette reminds faculty of learning opportunities, resources and upcoming events, such as discussions of best practices for remote office hours. “Some of the topics we are covering are topics that maybe none of us had ever thought about a year ago,” says Hopwood. “Take Zoom breakout rooms, for example. Few of us on the Sewanee faculty thought about that, but there are really good practices to keep students engaged.”

The Center for Teaching's dedicated space in duPont Library provides a home for faculty workshops.

The Center for Teaching's dedicated space in duPont Library provides a home for faculty workshops.

PRINCIPLE #2:

Leveraging University Resources and Developing E-Learning

In March 2020, Hawkins and Sandlin took over a space in Gailor Hall to start planning for helping faculty address the challenges they would face. The pair thought about the questions faculty would ask, such as “What is remote teaching? What tools do we need? How will people respond to these changes and what are the logistics?” They knew the answers were not straightforward. Some people were more ready than others, and some departments were more prepared than others. To get everyone on board, the team created a website to provide guides. “Betsy and I wrote a lot of this in Gailor 103 during those few days,” says Hawkins. “We covered a lot of the very basics that people would need to finish the semester.”

The successful pivot from intensive classroom instruction to online learning did not really surprise Hawkins. “When it comes right down to it, most people at Sewanee will go beyond expectations,” he says.

While technology has provided answers for the COVID classroom, it has not been the only source of answers, and in keeping with Sherwood Ebey’s desire to leverage many University resources to enhance teaching, the Center for Teaching has been active over the past year. “We have also reached out to other organizations on campus—the Center for Leadership and the Wellness Center among them,” says Hopwood. “We try to pull every resource we can to be successful.” Over the summer, Puckette and Hopwood, and others began developing training for the fall. “We spent a lot of time finding workshops in a variety of disciplines,” says Puckette: “We spent countless hours finding tools and making them widely known.”

In 2014, Betsy Sandlin and Deon Miles became co-directors of Sewanee's CfT after a survey of other centers for teaching across the Southeast was conducted by a team of Sewanee faculty and staff.

Instructional Designer Adam Hawkins (left) with current CfT Directors Emily Puckette and Mark Hopwood.

PRINCIPLE #3:

Experimental Approach and Repository

Since the inception of the CfT, directors and co-directors have managed a grant program to support faculty who want to experiment with teaching strategies. Grant funding has come from the University’s operating budget and endowment funds established in the 1990s as well as 10 years later by the Fund for Innovation in Teaching and Learning established by a Sewanee family from Louisville, Kentucky. Some years, these grants have supported big ideas—departmental overhaul of introductory courses, for example. In the year of COVID, some things have changed. “Instead of focusing on big grants for innovation, we have been giving out a lot of mini-grants,” says Hopwood, “and faculty are using them in clever ways: for example bringing in speakers, virtually, from around the country. In the past, when we wanted to bring in some expert, we always thought about doing it in person. The pandemic has changed the way we think about Sewanee’s connection to the broader world.”

“Faculty are pretty creative,” adds Puckette. “I always learn something.”

One recipient of a mini grant this academic year is Kerry Ginger, assistant professor of voice. “Knowing about the CfT was part of my decision to come to Sewanee,” says Ginger, who started her appointment in the fall of 2019. “It was a symbol of an abiding commitment to faculty growth and development and the quality of teaching. The Center for Teaching has a kind of symbolic capacity—showing that as a community we care about growing, enriching what we can do.”

One of the tragedies of COVID is that some of the fundamental activities of being human—conversation and, importantly, singing—become risky behavior, and teaching voice in COVID is especially challenging. Ginger and her colleagues have thought long and hard about how to teach this year. In-person voice instruction takes place in St. Luke’s Chapel, with the singer at one end of the chapel and the instructor at the other. Lessons are not scheduled back to back, allowing any virus droplets to settle out between lessons. And instructors also use Zoom, which is surprisingly effective, according to Ginger.

This year, Ginger applied for and won a mini grant from the CfT to bring in an artist from the University of Alabama, Alexis Davis-Hazel. Davis-Hazel conducted a master class via Zoom for the entire voice studio. “Students really respond to outside voices, to someone new who can see and hear what they are doing,” says Ginger. “The person from the outside has a way of framing that helps them learn.” Davis-Hazel worked with three students, focusing on lyric diction, tongue positioning, and other matters. Other voice students watched, and “that gives them a frame of reference, too,” says Ginger.

What’s Next: After the Pandemic

As Ginger’s experience shows, being able to extend the Sewanee learning community to colleagues around the world at the push of a button has opened many faculty members’ eyes to what is possible. “At this point, after completing the semester in the spring and getting the fall semester behind us, we are starting to think about what methods and modes we will keep after the pandemic is over,” says Hopwood. One sign that Sewanee has no intention of returning to business as usual is the new position created for Adam Hawkins as instructional designer. Hawkins’ new office next door to the CfT is a physical sign of the permanent transition that Sewanee faculty are making to meet the pedagogical challenges of the 21st century.

Last summer, as the second COVID-19 wave peaked and Puckette, Hopwood, Hawkins, Sandlin, and many others were running hard toward a new academic year, an economic analysis of higher education was being disseminated through the academic press. Scott Galloway, a professor at New York University developed an analysis that put American colleges in categories in a four-part matrix: thrive, survive, struggle, perish. Galloway argued that no college should have in-person classes in the fall because of the potential danger to students, faculty, and their communities, but he admitted that many would do so anyway out of economic necessity, and what he called a “tsunami of denial.”

The pandemic is not over yet, so all of us should reach for a handy piece of wood to tap, but so far, Sewanee has evaded Galloway’s dire predictions—though it has been a struggle. Students, faculty, and staff have eagerly signed on to an enterprise to ensure that a distinctive education happens in the COVID classroom. It turns out that Galloway’s frame, as compelling as it is, was just a little too reductive. He forgot that thriving almost always arises from struggle. At Sewanee, supported by a learning community nurtured over the last 25 years by the Center for Teaching, the struggle has turned on the imagination and untapped the genius of faculty. The Sewanee community has amply demonstrated the willingness to jump in to new endeavors supported by a thriving learning community that makes such experimentation possible.