Coding a Brighter Future

A unique summer-long program in Sewanee equips liberal arts students with the data-analysis tools they’ll need to change the world.

It’s elevator pitch day at Sewanee DataLab, a summer-long test of the proposition that liberal arts students can use the tools of data analysis to effect positive social change. Eric Keen, C’08, one of the faculty mentors, sets the scene for each student:

“You’re at a job interview at Google and they say, ‘What did you do last summer?’ You have one minute. Go.”

“You are at the airport waiting to board a plane and run into an old friend. She says, ‘So, what did you do last summer?’ Go!”

“You’re on an elevator in an office building in Pittsburgh, and Rayid Ghani steps on. ‘So, what did you do last summer?’ Go.”

As the real Rayid Ghani, C’99, is actually in the room through the magic of Zoom, that prompt is maybe the most realistic. Ghani, who is a distinguished professor of machine learning at Carnegie Mellon University, created the original version of DataLab at the University of Chicago nearly a decade ago with his Data Science for Social Good program. In late 2019, Ghani alerted Sewanee faculty and staff to the opportunity to join a nascent Public Interest Technology University Network (PITUN), a project of New America, an organization self-described as a new kind of “think and action tank.” As one of only four liberal arts colleges in the network, Sewanee was awarded a challenge grant and launched Sewanee DataLab in the summer of 2021.

So what is Sewanee DataLab? Here’s one elevator pitch: From nothing, Sewanee has created a summer institute that educates aspiring social changemakers to use data tools. They build marketable data analysis skills and frame their growing competence in a context of positive social change.

In a network populated by the likes of Carnegie Mellon, the University of Arizona, Princeton, and Stanford, Sewanee may be an unlikely candidate to push data analysis frontiers. But Joe Brew, C’08, who with his brother Ben, C’12, served as Sewanee DataLab instructors, believes data science is a perfect field for a traditional liberal arts college. “We are surrounded by data,” he says at the closing celebration for Sewanee DataLab. “We’re constantly sending data out to the cloud, and there are rooms full of smart people figuring out how to sell things to us using that data. But the era of Big Data does not have to be the era of Big Brother. DataLab is showing that at a liberal arts college, we can incorporate data analysis into the education of every student in every discipline, and those students can use their skills to make the world a better place.”

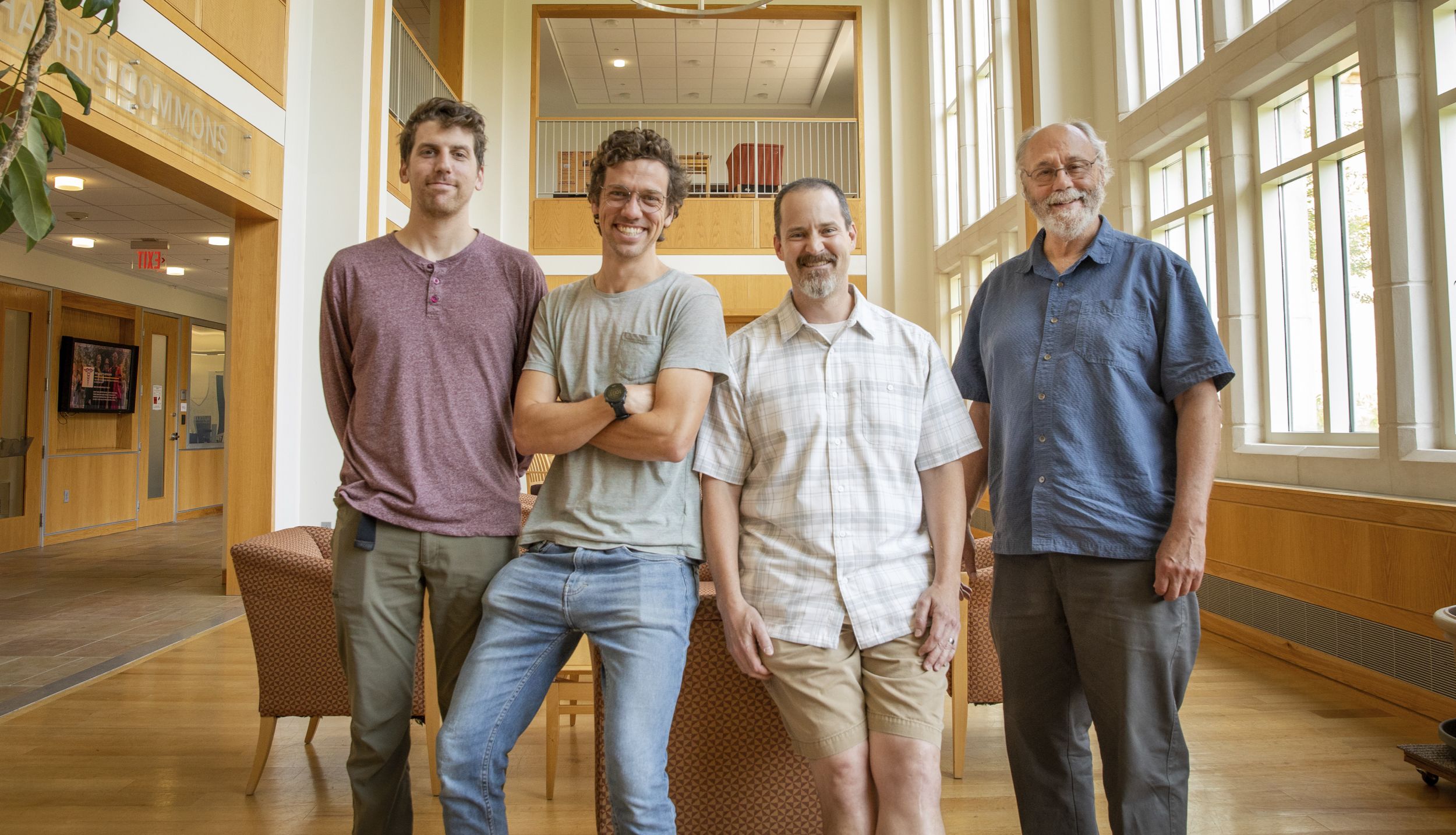

DataLab instructors and administrators: Ben Brew, Joe Brew, Matthew Rudd, and Jim Peterman. Not pictured: Vicki Borchers and Eric Keen.

DataLab instructors and administrators: Ben Brew, Joe Brew, Matthew Rudd, and Jim Peterman. Not pictured: Vicki Borchers and Eric Keen.

Sewanee DataLab 2021 took place over eight weeks in June and July. Eighteen students participated, including two students earning master’s of science degrees in public health from Meharry Medical College, which also partnered with Sewanee on a public health project in the spring. The summer began with a three-week data analysis boot camp. Students learned how to code in R, a free software programming language for statistical and image analysis. Then they chose a data analysis team and developed a “product,” a dashboard or interactive map, that presented data in such a way as to be useful to community members and policymakers. Along the way, they met alumni data scientists working in a variety of industries who came to campus or appeared over Zoom to provide career advice. They practiced professional skills, such as delivering elevator pitches, clarifying problem statements to communicate their work, and making full presentations to an audience of faculty, students, and administrators. After that presentation at the celebration event, Shehryar (Shehry) Khan, C’24, a member of Team Public Health beamed, “This was my first professional presentation.”

Teamwork was an important principle all along the way, from project conception in the summer of 2020—with PITUN institutional designee Jim Peterman and faculty director Matthew Rudd working with Tom Sanders on a grant proposal—to career presentations organized by Career Center Director Kim Heitzenrater, and marketing and communications by Vicki Borchers, who helped shape Sewanee DataLab’s public-facing activities. The original vision was consonant with Peterman’s approach to education. “I’m a philosopher by training, and I love my discipline,” he says. “I have been applying principles of Confucianism to community development as it relates to human flourishing and societal obligations. The Sewanee DataLab project integrates this view of ethics with the use of academic resources to train students to support the social change missions of partner organizations.”

“DataLab is showing that at a liberal arts college, we can incorporate data analysis into the education of every student in every discipline, and those students can use their skills to make the world a better place.”

Eric Keen took the lead on developing the R curriculum, which was, according to Joe Brew, designed to “get everyone to an inflection point where they can start to learn on their own, experiment with the skill, and get better.” One of the challenges was that some students came in with no training in coding, while others had a great deal. “In the real world, different people have different abilities, but we were able to use those different abilities to our advantage,” says Ben Brew. “Everyone helped each other, and we built a community that was able to accomplish the tasks we had in front of us.” Keen likens the Sewanee DataLab boot camp to an immersive language program. “We were like the Middlebury of data analysis,” he says.

Sewanee DataLab boot camp provided students with a baseline of skills in R, but the real work began with the formation of teams working on specific data projects, and every team was expected to develop a product that would have some kind of social impact. While students selected the projects they preferred, the final makeup of some of the teams became clear only as students responded to real-world challenges. By the first or second week in July, the students had settled into four teams: Team Broadband, Team Public Health, Team Photo, and Team Carbon. Shehry Khan’s Team Public Health started as two teams, but when promised data from a government source did not materialize, the students pivoted, finding a useful alternative by curating data from dispersed public data sources. Team Public Health also included the two master’s students from Meharry Medical College, who largely joined the group remotely via Zoom, but who came to campus for the final celebration. Essarah Hopkins, who with Kirstyn George joined Sewanee DataLab from Meharry, says that team-building was productive and that overcoming the challenges to the project together helped form a cohesive group.

Martha Clark and Jeremiah Studivant of Team Public Health meet remotely with a teammate.

Martha Clark and Jeremiah Studivant of Team Public Health meet remotely with a teammate.

Two teams working on image analysis of huge photo libraries (one for ancient art and the other for a community in Haiti) merged into Team Photo. Katherine Zelaya, C’24, explained the project this way: “The problem for our clients was that they had a large number of images and no way to come to conclusions about them.” Team Photo used machine learning (convolutional neural networks) to identify objects in photos, such as cell phones in the case of the Haiti photo archive, and recurring images in the case of the Ancient Art Archive project. Thanks to the team’s work, two artists, Professor of Art Pradip Malde and Stephen Alvarez, C’87, now have a tool that can begin to help them address the social impact of their work. For Malde, that impact is telling the stories of Haitian farmers, and for Alvarez, it’s capturing information about ancient art that is at risk due to factors including climate change and vandalism.

In the case of the Haitian project, the machine-learning model returned good results for identifying objects in photos, but the Ancient Art Archive project required more work. Machine-learning models need to be trained, and the model the team used had been pre-trained, making it more likely that people and everyday objects could be identified, whereas stylized and ritualized images in ancient art might not, as Pratham Singhal, C’24, explained. The team saw that deficit and came up with a plan for the Ancient Art Archive project. Over the coming months, Ngan Nguyen, C’24, explained, team members will develop and train a new model specifically for rock art.

Team Photo’s experience exemplifies an important feature of a program like Sewanee DataLab: The final results might come much later. “A lot happens before an event like this, and a lot happens afterward,” says Rayid Ghani. “What happens after is really just as important for the impact you are hoping for.” As an example, Ghani relates a story of Joe Brew’s involvement with Data Science for Social Good at the University of Chicago in 2014. Brew’s team came up with a model to predict where children would be at risk of exposure to lead, but it wasn’t until four years later that the model was made more robust and was implemented by the City of Chicago to address a public health problem.

Students from a variety of disciplines joined Sewanee DataLab, but in many cases, whatever their academic goals, they were motivated by a strong desire to be positive changemakers. “I joined DataLab because Dr. Peterman told me it would be a really great learning experience, and he was right,” says Caroline Willett, C’23. “The biggest challenge I faced personally was having no background in data science, but the Brews really made it accessible and easy to learn in a fast-paced, high-energy environment.”

Willett was one of three members of Team Carbon, with Kate Baker, C’22, and Nika Gorski, C’22. Team Carbon worked with Professor Deborah McGrath, whose long-running Zanmi Kafe carbon project in Haiti had amassed a great deal of data about tree growth. Zanmi Kafe is an innovative small carbon market that Sewanee runs in partnership with farmers in the hilltop community of Bois Jolie, Haiti. Farmers grow trees, and Sewanee pays them for the carbon they have sequestered, partially offsetting the carbon emitted by Sewanee outreach trips. Team Carbon’s task was both to figure out the best method for calculating the amount of carbon sequestered and to make the data easily presentable to the general public.

Team Photo members Katherine Zelaya and Dirk Kayitare used machine learning to identify objects in photos for two separate projects.

Team Photo members Katherine Zelaya and Dirk Kayitare used machine learning to identify objects in photos for two separate projects.

“Our work has promoted real social change, and the purpose of our project really resonated with all of us,” says Willett. “The work we’ve done will help move the Zanmi Kafe project forward and help to reduce Sewanee’s impact on the environment.”

For a team photo, Willett held up her laptop, so that her teammate, Nika Gorski, could be in the picture. Gorski was one of several students who participated virtually, and each team worked hard to overcome the complications of working together remotely. “Every person and every team contributed something beneficial,” says Gorski. “Knowing that my team and I helped a group in Sewanee and people in Haiti is very humbling.” For Dirk Kayitare of Team Photo, keeping remote team members connected was a matter of constant communication. “One thing that we understood about our team dynamic was that we had to check in every day about meeting times and different tasks that had to be done because our project had so many moving parts. The disconnect was often in keeping track of the progress that was made between the in-person versus the remote folks. One thing that helped us a ton was the enthusiasm that everybody on our team had.”

Joe Brew describes Sewanee DataLab 2021 both as “the first pancake,” and “like building an airplane as it’s rolling down the runway.” Whichever metaphor you choose, one of the ingredients was ensuring that the program was inclusive of students from diverse backgrounds. Sewanee DataLab 2021 included African American students, Latino students, an Egyptian American from Nashville, and foreign nationals from Rwanda and Nepal. Dirk Kayitare, a native of Rwanda, was a pillar of Team Photo, and a fellow Rwandan, Feza Umutomi, C’22, lent her talents to Team Broadband.

The goal of Team Broadband was to build a comprehensive database of broadband-access assets, including libraries and other public access points. As part of the project, Umutomi, with team members Pravesh Agarwal, C’23, and Zach Shunnarah, C’23, interviewed members of the public to identify needs. In addition to showing the connection between broadband assets and population, the team’s interactive map shows exact locations of broadband access points to help the general public. Having had experience building the broadband map, Agarwal took on a related project, building an interactive map for the South Cumberland Health Network, which will be populated with data by a VISTA member working with that organization.

Most of the work for the Sewanee DataLab took place in Harris Commons in Spencer Hall, and the space became a hive of activity, with the Brews and Eric Keen taking up residence by a curiosity cabinet full of taxidermied bobcats and birds, animal skulls, and mounted insects. Matthew Rudd moved from table to table talking over projects, and Jim Peterman dropped in to hear and contribute to presentations. Along the way, a new grant proposal was coming together, an expansion of the program that will bring in partners from the Appalachian College Association and the Algernon Sydney Sullivan Consortium.

“I’ve been working on projects like these for the better part of a decade, and they are hard to put together,” says Ghani. “So why are we putting in all this effort?” For Ghani, the answer to that question is tied to his own experience understanding the connections between what he is good at and what he cares about. But he also thinks that connecting values and technical competence is critically important. “What are the values we want the world to have? You can build a system to be efficient. That sounds reasonable, but what does that mean? You will help the people who are easiest to help and leave behind the ones who are hardest to help.” For Ghani, equity is a transcendent value, which is one reason he believes it is important that liberal arts students are brought into this technical world. “Looking at DataLab, I’m really excited that the technical piece and values piece are in the same place. We are operationalizing both, and we are training both.”

Team Public Health members Shehryar Khan and Mehrael Ibrahim prepare for a presentation.

Team Public Health members Shehryar Khan and Mehrael Ibrahim prepare for a presentation.

In his closing remarks, Joe Brew hammers home that point. “Rayid’s most valuable lesson is that data science is a powerful weapon that you can use for evil or good. If we don’t aim the weapon right, we are in really big trouble. Who, if not Sewanee, can show young people that wanting to change the world is not some ambition you shed in your late 20s but is something that you can carry with you for a lifetime?” For Brew, and for everyone involved this summer in Sewanee DataLab, it seems clear that data science both has a connection to all the disciplines in the liberal arts and is itself a liberal art, bringing together diverse teams of people, creating products that move the arc of history a little bit closer to justice, and helping students acquire skills they will need to succeed in this world.

To learn more about Sewanee DataLab, visit datalab.sewanee.edu.