Black History Month, Black Lives Matter, and Beloved Community

How Persons of Color Are Seeing the Movement Today

If we needed a reminder that we, as a nation, have a long way to go towards an equitable society, the killing of Amir Locke two days into Black History Month, in the same city where three police officers are currently on trial for killing George Floyd, is that reminder. While the specifics of the Locke case and the validity of the “no-knock” warrant that authorized the police to enter the apartment where Locke was sleeping are currently under review, there can be no doubt that we have a serious problem in this country; a problem that, as Presiding Bishop Curry said in 2020, “is baked into the very fabric, if you will, of the cake of our country.” Speaking of George Floyd’s murder in 2020 and the civil unrest that followed, Curry explained that “the deeper pain of this is the fact that it’s not an isolated incident. The pain of this is that it’s a deep part of our life. It’s not just our history. It is American society today. We are not, however, slaves to our fate, unless we choose to do nothing.”

Choosing to do nothing is not an option in Sewanee. Just as in The Episcopal Church and the nation, confronting systemic racism on campus has required asking difficult questions, inviting uncomfortable conversations, and reckoning with the sins of the past. One of the most important aspects of these efforts, an aspect which the Presiding Bishop has repeatedly emphasized, is the collecting of stories, of real-life narratives. “Our stories have power,” he writes in Love is the Way. “They have power to change how people understand the world—but even before that they have the power to heal the storyteller.” As part of its efforts to move towards Beloved Community, The Episcopal Church has made a concerted effort to collect the stories of Black Episcopalians and share them. With the same goal of fostering understanding, Features wanted to hear from Black students and alumni.

The Brother You Have Seen

In 2018, Bishop Curry announced that The Episcopal Church would undertake a racial justice audit. The purpose of the audit, he explained, lay in “facing painful truths, and working together...to build a decent, humane society.” To do this, Bishop Curry said, we would have to take a realistic look at racism that is “structural, institutional, as well as personal and interpersonal,” all of which “become factors of how we live our life together as the Body of Christ.”

The audit, which was conducted from 2018 to 2020 in partnership with Mission Institute, did not seek to answer whether racism exists in the Church; that was a given. In introducing their findings, in fact, the audit reporters wrote, “The goal of this research has not been to determine whether or not systemic racism exists in The Episcopal Church, but rather to examine its effects and the dynamics by which it is maintained in the Church structure.” The dynamics that protect and sustain institutional racism, the audit reported, largely follow nine patterns. These patterns range from using transactional relationships to theological language to uphold the status quo, which, in The Episcopal Church, is dominated by white concerns and history. Understanding these dynamics, the audit suggested, is the first step. “Oftentimes what keeps harmful systems and behaviors in place are the hidden norms and standards that get passed off as normal, respectable, good, and just the way things are. These hidden norms are what make up white dominating culture.” (Racial Justice Audit Report, 31) In Bishop Curry’s opinion, undoing the stranglehold of white dominance and allowing everyone a seat at the table comes down to a simple passage in the Gospel of John: Those who say, “I love God,” and hate their brothers or sisters, are liars; for those who do not love a brother or sister whom they have seen, cannot love God whom they have not seen. (1 John 4:20)

The work The Episcopal Church has undertaken is critical, says Audra Ryes, T’24. “One of the most impactful actions of the Church was the commitment to educate all stakeholders about the evils of systemic racism, and the importance of undoing those systems,” she explains. “I am very pleased that The Episcopal Church has required anti-racism training for all parishes, and I’m also very happy that many individual parishes have written racial reconciliation programs into their bylaws.” Doing so, Ryes believes, will allow parishes to become more diverse spiritual communities. Furthermore, another important action the Church has taken is “the acknowledgement of its role in the oppression of People of Color and other marginalized groups,” Ryes says. “The Church has made public statements of solidarity and respect for all People of Color, and there is a commitment to becoming anti-racist churches that work towards racial reconciliation, reparations, and racial healing.”

A #Movement is Born

Dismantling white dominating culture and confronting racial injustice has been the life’s work of numerous leaders, some with notable public personas like Martin Luther King Jr., W.E.B. Du Bois, and Sojourner Truth, and some with less well-known names, but remarkable personal courage and conviction, like Fannie Lou Hamer and Pauli Murray. Today, with words moving at the speed of Tweet and cellphone cameras capturing moments that would otherwise have gone unseen, confronting racial injustice has become a collective act, the work of millions of people around the world using the tools in their hands to record acts of violence, disseminate information, spark outrage, and affect change.

Given the power and prevalence of social media in today’s culture, it is fitting, then, that the Black Lives Matter movement began with a post. The movement, which “has grown from a hashtag to a protester’s cry to a cultural force that has reshaped American politics, society, and daily life,” as New York magazine characterized it recently, began when Alicia Garza, one of the movement’s founders, shared her disgust with the acquittal of George Zimmerman, the man who killed Trayvon Martin. She posted on Facebook using the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter, and the hashtag, and eventually the movement, caught fire in the US, UK, and Canada. The mission of Black Lives Matter, according to its founders, is “to eradicate white supremacy and build local power to intervene in violence inflicted on Black communities by the state and vigilantes. By combating and countering acts of violence, creating space for Black imagination and innovation, and centering Black joy, we are winning immediate improvements in our lives.”

Not Gone, Just Underground

For Ryes, the Black Lives Matter movement is the continuation of the work begun during Reconstruction in the 1800s, made necessary by the fact that “we are still fighting to be seen as equal human beings in this country. You had a population of formerly enslaved people who helped build this country and who wanted to be seen as equal human beings,” she says, “who fought to be heard and seen as contributors to the American Dream. That fight continued after the Civil War, during Jim Crow and the Civil Rights Movement, and it still continues today.”

Gwendolyn Dickey, C’25, was still quite young when Black Lives Matter was gaining traction and growing as an organization, but she says the movement has had a significant impact on her life. “Black Lives Matter prompted a lot of conversations in my hometown of Memphis,” Dickey says, “about police brutality, racism, Trayvon Martin, and of course all that came afterwards, like George Floyd and Brianna Taylor. It brought people of different ages and demographics together and gave them an opportunity to understand how important these issues are for People of Color.” While not everything about Black Lives Matter has been positive—it would be hard to find a movement or organization without flaw—Dickey sees the movement as the “Black Panthers and Civil Rights efforts of my generation, shining a light on the need to educate people about the Black experience.”

Cyrus Wilson, C’24, also sees the Black Lives Movement as a helpful tool, especially when it comes to bridging generational and racial gaps. “I grew up in Maryland, and throughout high school we would have protests all the time. We would have marches, walkouts, and black t-shirt days,” Wilson says. “My parents and grandparents have both expressed their support of the movement, and in my hometown, it was picked up by all generations of all races. We would have white, Black, Hispanic, and Asian people all at the protests.” While Wilson saw the movement’s success as a community building tool, he knows that, to some, the Black Lives Matter movement is problematic. “I think it is because they misunderstand the purpose of the movement and think it will lead to division of our country. I wish people would focus on the title of the movement, because that is the main message we are trying to push, that “Black Lives Matter,” Wilson explains. Dickey agrees that for some people, Black Lives Matter has been a difficult organization to get behind. But, she says, “it is critical to educate people who think racism has gone away. Racism never went away, it just went underground.”

“The Past is Never Dead. It’s Not Even Past.”

The Black Lives Matter movement, much like the #MeToo movement, has created a powerful wave of reckoning, forcing those who would rather close the door on the unpleasant aspects of history to acknowledge that what happened in the past is relevant and does matter, because the past has shaped the present. In the spirit of William Faulkner’s line in Requiem for a Nun, “The past is never dead. It’s not even past.” Until past injustices are recognized and dealt with, these movements insist, they will continue to shape the future.

Sewanee’s efforts to acknowledge and account for its past have resulted in several visible changes on the Domain. Otey Memorial Parish, which was named for James Hervey Otey, the first bishop of Tennessee, who was also the first chancellor of the University and a slave owner, was renamed The Episcopal Parish of St. Mark and St. Paul on the Mountain in January of 2021. Why the double name? When the church was first built in 1875, on the site of what is now Sewanee Elementary School, both a white and a Black congregation worshiped there, albeit at different times. The white parishioners called their house of worship St. Paul’s on the Mountain, while the Black parishioners called their church St. Mark’s. The new name not only severs the direct connection between today’s church and the slave-owning Otey, it also symbolizes the desire to unite all Episcopalians on the Mountain in a common future.

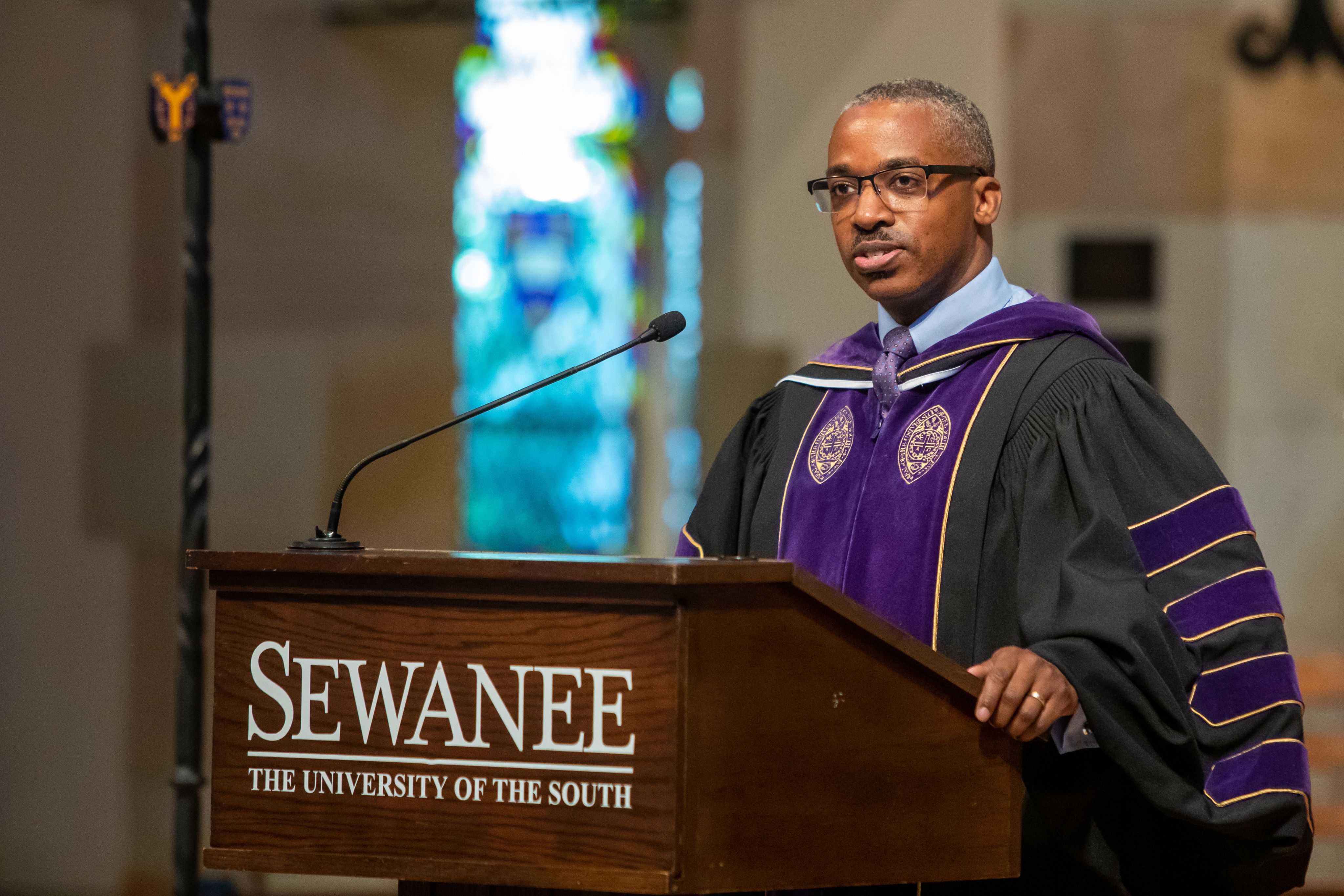

Disconnecting from slavery is the same reason the Dubose Lectures, hosted by the School of Theology each fall, has a new name. Originally named for William Porcher Dubose, who became dean of the School of Theology in the mid-1890s and was vocal about his belief that slavery was not sinful, the lectures are now called the Alumni Lectures. The Rev. Dr. Benjamin King, academic dean of the School of Theology, explained the name change this way in April of 2021: “Theology always arises in a context. Even if DuBose’s theology retains an international reputation, his writings on this region and on race bear witness to his context. DuBose is not the name that best represents our context and what the School of Theology and our alumni have to offer the 21st-century Church.” Racial reconciliation was at the core of the newly named Lectures in 2021, which featured the Rt. Rev. Phoebe Roaf, bishop of the Diocese of West Tennessee; the Rt. Rev. Jennifer Baskerville-Burrows, bishop of the Diocese of Indianapolis; and the Rt. Rev. Eugene Taylor Sutton, bishop of the Diocese of Maryland.

Much of the wrestling Sewanee has done with its past has arisen from the University’s Roberson Project on Slavery, Race, and Reconciliation. The name commemorates the scholarship of Houston Bryan Roberson, Sewanee’s first tenured Black professor, and the project has sponsored several initiatives around campus to recapture and archive the stories of the Black men and women who shaped Sewanee’s history, as well as restore several physical structures of historical importance to the Black community and educate the public through reading and discussion groups. The Roberson Project explained its work and its relevance in its Research Summary, saying that the purpose of the Project is to “grapple with these challenging and urgent questions of race and equality” and “to engage the racial and economic disparities that exist in our host communities.” To do so, the Project’s leadership writes, “holds out the hope and possibility that the people of Sewanee have long imagined as their historical destiny: to make this place a model, not just in, but of and for the South and the world beyond it. By knowing and acknowledging the centrality of slavery and its legacies in their history and traditions, the people of Sewanee may pursue this task in a way that binds and heals the wounds of racial injustice.”

First, Reveal the Wounds

The Executive Report that opens the Roberson Project’s Research Summary makes it clear that the project’s leadership has no interest in sugarcoating the University’s history. The first bullet point is this one: The University was the only institution of higher education designed from the start to represent, protect, and promote the South’s civilization of bondage; and launched expressly for the slaveholding society of the South.

The second bullet point explains why it was believed that such a university was necessary: A primary justification for the University’s founding asserted that the white men of the South were positioned better than any other to make the highest contributions to world civilization because slavery allowed them to devote themselves to higher attainments. The organizational blueprint for the institution indicates the founders envisioned the University as a leading center of scientific scholarship proving white racial superiority and the “aptitude” of people of African descent for enslavement. The report goes on to detail, in no uncertain terms, how the University benefitted from the wealth of the slave-owners who founded and supported it.

Another facet of the Roberson Project is the Sewanee Place Name Journal, which provides an interactive map of the origins of various place names on the Domain. Under the leadership of then Vice-Chancellor Brigety, the University also created the Names and Places Committee. This Committee is tasked with identifying the buildings on campus named for benefactors with ties to the Confederacy, and is part of the effort to address what Brigety called “the gaping wounds of racial injustice” in Sewanee’s past.

For King, who is a member of the Roberson Project’s Working Group, the value of the project to the University, and to King himself, is clear. “The Roberson Project is now such an integral part of the University’s identity that when, in September 2020, the regents categorically rejected “past veneration of the Confederacy and of the ‘Lost Cause,’“ they grounded their statement in the historical research that some colleagues and I had done,” King explains. “It’s exciting to be part of a university that uses its own faculty’s research to uncover past sins, and, as the regents did, to commit to concrete change in the present. And because the university is part of The Episcopal Church, members of the Roberson Project from the School of Theology might be particularly well placed to help the university consider ways to repent and make restitution.”

Ryes agrees that the work of the Roberson Project is already making a difference. “Part of my decision to pursue my degree at Sewanee was the work of the Roberson Project, and the work of reconciliation that is ongoing on campus. It is slow, hard, ever-evolving work, but the commitment the University is making to provide the voice and perspective of the Black community in Sewanee’s narrative is vital. It is critical to any and all of the decisions made for improving the University as an institution of excellence.”

An American Story

Sewanee is not, of course, the only organization confronting the demons of its past. That is an undertaking the University shares with hundreds of other esteemed institutions in the U.S. and U.K., such as Brown, Yale, Georgetown, Lloyds of London, JP Morgan, Bank of America, the Bank of England, and, of course, The Episcopal Church. Many of these organizations have also changed the names of programs and stripped their buildings of slave-owning donors and founders. But does changing the name of a parish church or an academic building or a lecture series actually matter? Are removing those names meaningful acts, or are they simply performative value-signaling?

Dickey believes name changes and reconciliation projects do matter, although she wishes the initiatives at Sewanee were more widely known on campus. “I do appreciate the efforts,” she explains, “but I wish that the slavery in Sewanee’s past wasn’t under the radar. It would be good, for instance, if students who were thinking about coming to Sewanee were made aware of the school’s desire to disassociate from that past.” Dickey explains that, because these efforts are not well known, her decision to attend Sewanee was not fully supported by everyone she knew in Memphis. “Everyone understands that it’s a great education. And don’t get me wrong, I am incredibly grateful for this opportunity and this education. But being Black here is not a cake walk. And if more people knew about Sewanee’s past, and how much Sewanee wants to move on from that, it might make it easier to be Black here.”

Wilson agrees that being Black on campus is not always easy. “I think a lot of Black people on campus are uncomfortable,” he explains. “We feel the history of this school whenever we walk into a classroom, or a fraternity house, or the library. The university has made tremendous strides in reconciling with the past, but there needs to be more done by the students to make Black people feel welcome into the community.”

Being a Black person on the Sewanee campus, Ryes agrees, is a challenge because “being a Person of Color in America is a challenge. The same dynamic that exists off the Domain isn’t necessarily different on campus.” What is significant, though, she says, is that the Black population on campus is so small. This means, she explains, that “something as simple as getting a haircut or hair braided or hair locked isn’t provided on campus because it’s not part of the dominant culture’s experience. So those things have to be done off the Mountain, which affects travel and time and budgets for Black students.”

Wilson agrees that being Black at Sewanee can be difficult, and says he believes “the University still has a long way to go, because we’ve only taken the step of acknowledging our past, but have done little to figure out a different way going forward. Vice-Chancellor Brigety wanted to do that. He was proof of the University making steps to change the trajectory of the school.”

Indeed Brigety, who recently resigned his position at the University to accept President Biden’s nomination to the Ambassadorship of South Africa, was a very visible representative of the University’s plans for a more equitable future. Brigety believed, as he explained when announcing his plans to return to diplomatic life, that “Sewanee’s story is an American one, of vital ideals calling it forward, of profound challenges and stronger determination.”

Moving Forward

While it remains to be seen who will fill Brigety’s shoes as the next vice-chancellor, it is clear that there is still work to be done at Sewanee when it comes to creating a world that offers equal opportunity and welcome for all, just as there is in The Episcopal Church and in American society.

For every step forward there are backward tugs in the form of new issues that threaten to undo progress like gerrymandering, prohibitions against assembling, and threats to Second Amendment rights. Unfortunately, Ryes says, “The erosion of Black rights is nothing new. In 1868, we had close to 2,000 Black men holding political offices in this country. By 1877, thanks in large part to laws designed to intimidate Black voters, things were changing radically,” she explains. “There were groups of white people who strategized, politically, to suppress Black votes and to reverse rights and freedoms using legislative loopholes and financial barriers. We are seeing the same tactics of suppression today.”

Those things also concern Wilson, who sees proposals like requiring identification at the polls as a way to impede Black people’s right to vote, but Dickey thinks there might be an even bigger danger lurking. Her grandfather, she explains, came of age during the violence and unrest of the Civil Rights movement. “He’s been through a lot,” she says. “He was born in 1945, and we talk a lot about what led us to this point, all the suffering and sacrifices to get the rights that Black people have today. And to me, the scariest thing isn’t the attempts to remove those rights. It’s the apathy of people my age who aren’t in college, who aren’t having these conversations, and who are becoming dangerously comfortable with their rights being taken away.”

“Black people are also people.”

Black History Month has been celebrated in the U.S. since 1976, but its roots go back to 1915 and the Association for the Study of Negro Life and History, founded by author and historian Carter Woodson. Woodson is only the second Black man, after W.E. B. DuBois, to receive a Ph.D. from Harvard, and the first child of slaves to do so. He led the association with minister Jesse Moorland, and urged the nation to celebrate Negro History Week, which it did, beginning in 1926. Thanks in large part to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1960s, the celebration of Negro History Week became more widespread, and in 1976, then-President Gerald Ford officially recognized Black History Month, urging Americans to “seize the opportunity to honor the too-often neglected accomplishments of Black Americans in every area of endeavor throughout our history.”

Ten years later, Congress put Black History Month on the national calendar, and then-President Ronald Reagan issued Proclamation 5443, which stated: “The foremost purpose of Black History Month is to make all Americans aware of this struggle for freedom and equal opportunity. It is also a time to celebrate the many achievements of Blacks in every field, from science and the arts to politics and religion. It not only offers Black Americans an occasion to explore their heritage, but it also offers all Americans an occasion and opportunity to gain a fuller perspective of the contributions of Black Americans to our Nation. The American experience and character can never be fully grasped until the knowledge of black history assumes its rightful place in our schools and our scholarship.”

For Ryes, Black History Month is a special time of recognition for, and celebration of, Black contributions to this country, and Ryes says she is definitely appreciative of the events that highlight Black people as trailblazers and agents of change. “But I’m also reminded during Black History Month that in the narrative being presented, these Black Americans are deemed significant because someone white has validated their efforts.” There are many Black Americans who work within their own communities to help people of all ages, she explains, but who never get recognition because their work only benefits other Black people. And furthermore, she says, “I’ve seen how important Black leaders have been targeted as enemies of America simply because their philosophies don’t benefit white Americans. It seems that Black Americans are only important if they make an effort to cross over racial lines. That’s sad.”

Poet Nicki Giovanni, who was awarded an honorary degree by Sewanee last month, captured the importance of Black History Month to Black Americans in her poem BLK History Month, published in her 2002 book, Quilting the Black-Eyed Pea. In the poem, Giovanni compares Black History Month to seeds on fertile ground, nourished by the forces of nature that tell the seeds, “You’re as good as anybody else, you’ve got a place here, too.”

That feeling, of having a place, of belonging and being valued, is something Feza Umutoni, C’22, took for granted as a child in Rwanda. “Everybody there looks like me, Black, so I am not constantly aware of my color because there is no need to be. I didn’t need to be reminded that Black people are smart, because I encountered people that were smart and they were Black,” she explains. “I knew I could be a doctor, an engineer, just like the way I could be a janitor or maid depending on how life unfolded. Hence growing up, I belonged by default, and didn’t feel any underrepresentation.” That changed when Umutoni arrived in the United States in 2018. “Having to deal with topics like racism and microaggression was quite a change for me. I can see why Black History Month is important and could be beneficial to a nation like the United States that seems to still need a reminder that actually Black people are also people.”

When it comes to designating a month to commemorate Black achievement, however, Umutoni believes it is not enough. “No great change has ever come from one month of work per year. Black history should be discussed on a daily basis and year after year, taught, performed, showcased, appreciated, otherwise it just rusts and rots,” she says. “We can all agree that telling someone “You’ve Got A Place Here, Too” when the system in place says that they don’t is like telling someone, “You know you can sit, right?” but making sure that they don’t get their hands on any chair in the room. That means that if they happen to sit, they will either sit on the ground or have to steal the chair to sit on.” Besides, Umutoni says, it is not Black people who need to be told that they have a legitimate right to exist and an inherent value. “The ones that mostly need to hear that Black people belong in the United States are not us, the marginalized Black people. It’s the people in positions of power. The president, the senators, the governors, the professors, the teachers, the doctors. Anybody in a position to make a decision, and whose voice and actions can actually change the system. Those are the people who need the message.”

Representation is Reality

Wilson sees Black History Month as an effort to acknowledge American history “that goes untold in many schoolbooks and lessons,” but he believes more needs to be done to include Black history in education. “Black history needs to be important to everyone, not just Black people, because it affects all of us.” Dickey believes that Black History Month is important, too, just as representation in society and popular culture is. “Seeing Black people in positions of authority and leadership is so important,” she says, “especially to children.” Dickey remembers that as a child, she used to watch Sleeping Beauty, and had the princess costume and wig of the movie’s title character. “I wore that costume and wig a lot,” she says, “until one day, my mom threw it out. I didn’t understand why then, but I do now. I put that wig on to be someone different, someone who was actually represented on TV and in the movies. I understand now how painful it must have been for my mom to watch her child yearn to be something other than what they were. Something unachievable.” Children today find it easier to see themselves reflected in pop culture, Dickey says, and that is important. “I have a five-year-old niece, and she can dress up as someone who looks like her. Representation is her reality.”

While it may seem unimportant to white people, who have always seen themselves reflected in popular culture, Wilson agrees that “representation in movies and such is extremely important when it comes to feeling comfortable and accepted. The other day I watched the children’s movie Encanto,” he says. “It’s about a Hispanic family and their magical powers. In the movie, there were people of all skin tones, as well as interracial couples. After I watched the movie, I went on Instagram and saw a picture of a little Black boy pointing at his TV and smiling. He was pointing at one of the main characters, who is also a little Black boy with big curly hair. I felt so happy for this little boy, and for my own inner child.”

“A gospel I want to be part of.”

The Atlantic recently published an essay about Encanto, suggesting that the message of the movie is “America is broken (but don’t worry, all is not lost).” In other words, for all of our many problems, there is work being done that moves us further down the road to reconciliation, and it is important to recognize that progress, even when it is incremental. As poet Nikki Giovanni explained in an interview at Appalachian State, “My generation has to remind the younger generation [that] we grew up in segregation and we took segregation down. So what we handed the next generation, my son’s generation, for example, is an unsegregated world or a desegregated world, however you want to look at it. But it doesn’t mean a world without racism.”

That message, about recognizing and celebrating progress while working for more, is, in its essence, the same one Bishop Curry has been delivering for years. In his book Crazy Christians: A Call to Follow Jesus, Curry shares a story about his father’s first visit to The Episcopal Church, where he witnessed an act that would not have been possible earlier in American history:

“My father didn’t feel comfortable going up for communion, but when my mother went up, he watched closely. Was the priest really going to give her communion from the common cup? And if he did, was the next person really going to drink from that same cup? And would others drink too, knowing a Black woman had sipped from that cup? He saw the priest offer her the cup, and she drank. Then the priest offered the cup to the next person at the rail, and that person drank. And then the next person, and the next, all down the rail. When my father told the story, he would always say: “That’s what brought me to The Episcopal Church. Any church in which Black folks and white folks drink out of the same cup knows something about a gospel that I want to be a part of.”

That Gospel, that calls us to share the cup, is the same one that has motivated both The Episcopal Church and Sewanee to shine a bright light on corners of history that were more comfortably left in the dark. Doing so is not easy, says the Rev. Joseph Wallace-Williams, T’12, rector of The Church of St. Luke and the Epiphany in Philadelphia, “but having a sacred confrontation with both Sewanee’s history and its present reality is what will expand our hearts, and the hearts of those who come after us to the Mountain.”

After all, Bishop Curry reminds us in Crazy Christians, “being a Christian is not essentially about joining a church or being a nice person.” Instead, being a Christian is about “following in the footsteps of Jesus, taking his teachings seriously, letting his Spirit take the lead in our lives, and in so doing helping to change the world from our nightmare into God’s dream.” Achieving that dream, says Wallace-Williams, means “building the kingdom of God brick by brick, thought by thought, person by person, with hearts that are decayed by racism, but still beating, and still giving life.”