A Year of Verse and Song

Meet Sewanee’s two newest Watson Fellows, who will travel the world to explore the origins and redemptive power of art through poetry and music.

There are few opportunities for graduating college seniors that induce as much joy and jealousy as a Thomas J. Watson Fellowship—a fully funded year of international travel to pursue a project of the fellow’s own devising. Competition for the coveted fellowships is stiff among students at the Watson Foundation’s 41 partner institutions, but Sewanee students have fared particularly well, earning 51 awards over the past 36 years.

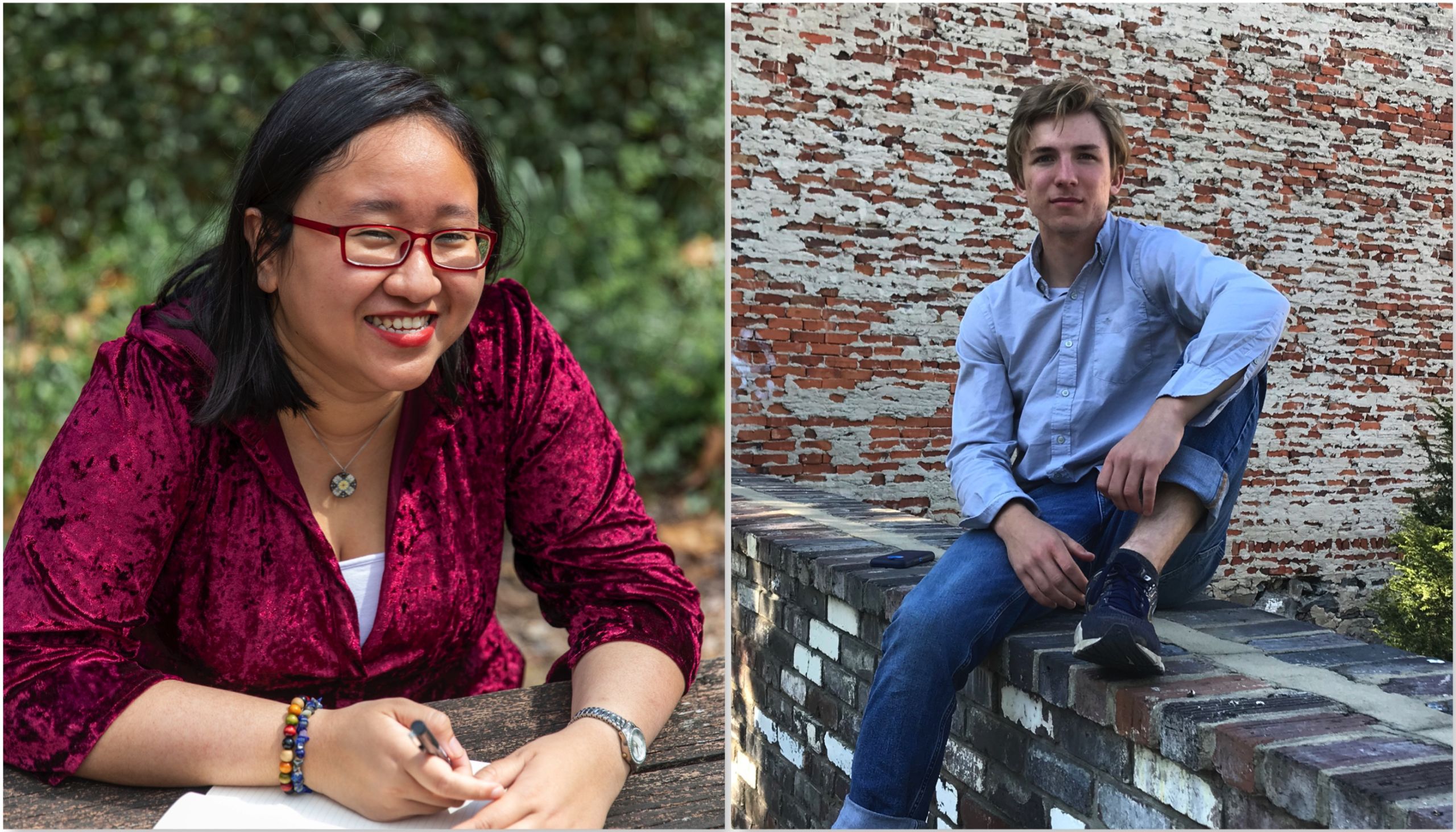

This year, two more extraordinary Sewanee seniors have been named Watson Fellows, and they’re each looking forward to a year of travel and self-directed learning. Mandy Moe Pwint Tu, C’21, and Bramwell Atkins, C’21, will both pursue projects centered on the arts: poetry for Tu, and music for Atkins.

The downside of being awarded a Watson Fellowship in 2021 is not knowing when you might be able to board a flight to begin the journey. Due to COVID-19-related global travel restrictions, Sewanee’s newest fellows may have to wait an extra 12 months to begin their Watson years. But whenever they hit the road, Tu and Atkins will be ready for a once-in-a-lifetime year of mind-expanding exploration.

Mandy Moe Pwint Tu, “Voices in Verse: Perspectives on Postcolonial Women Writing”

Mandy Moe Pwint Tu, C’21, grew up in an English-speaking household, in an English-speaking community, going to English-speaking schools in Yangon, Myanmar (formerly Burma). It’s what was done in certain segments of society in Myanmar, where the native language, Burmese, was seen to offer less upward mobility and where young adults were encouraged to leave the country to seek opportunities in more prosperous parts of the English-speaking world. Only after leaving Myanmar, first to study in Australia and then in Sewanee, did Tu start to feel like something was missing—she didn’t speak the language of her homeland.

This was particularly problematic because Tu is a poet whose work often focuses on the land of her birth. “My poetic journey has taken me many places, but one thing that’s been consistent is my relationship to Burma,” she says. “The farther away I go from it, the more poems I write exploring the nature of that relationship.”

The English spoken in Myanmar is a vestige of the country’s turbulent political history, which includes 63 years of British rule from 1886 to 1948. The Myanmar of Tu’s childhood was a postcolonial state under domestic military rule. When a civilian government took power and instituted democratic reforms, Tu co-founded a literary magazine to celebrate the voices of Burmese artists when she was just 20 years old.

When it came time to dream up a Watson proposal, Tu thought hard about her personal interests and asked what kind of project could sustain her for an entire year. She arrived at the answer by looking inward. “Part of it was just figuring out what I’m passionate about, and that’s poetry and especially postcolonial poetry,” she says. “It’s a combination of some of the questions I’ve been asking since my work with the Yangon Literary Magazine and here at Sewanee being in an English department that has maybe two or three classes on postcolonial lit. I want to know if there are other women poets who have experiences similar to mine.”

The experiences Tu hopes to explore during her Watson project include artists’ often complex relationships with their home countries, the formation of identity in the shadow of colonial history, and tensions between writing in English and writing in the mother tongue of a poet’s native land. In other words, she hopes to ask others questions she’s been asking herself for years. As Tu wrote in her Watson proposal, “I still carry the questions that I had coming into my first year [at Sewanee]: What does it mean to be a postcolonial woman writing in the language of her colonizers? Does my complex relationship with Myanmar invalidate my Burmese identity?” To learn from women poets writing from a postcolonial perspective, Tu will travel the world, hopping from one former British colony to another until she ends her Watson year in Great Britain itself.

Tu will begin her journey in Malaysia, where she plans to meet with poet Angelina Anthea Bong to learn from her and other women poets about how their work reimagines traditional Malay poetic forms. In Singapore, the hub of the Southeast Asian publishing world, Tu will explore opportunities for marginalized artists in a flourishing literary scene and sit in on creative writing classes with poet Pooja Nansi. In South Africa, she’ll explore sites of historical oppression and learn how they affect and are in turn informed by poetic expression. She’ll meet renowned local and international poets at the Lagos International Poetry Festival in Nigeria before heading to the Caribbean to meet young writers in the creative writing program at the University of the West Indies in Jamaica. In the Bahamas, she’ll meet the founder of a literary journal for women to discuss the importance of new platforms for showcasing creative work. Finally, in England, she’ll seek out contemporary minority women poets from postcolonial states to understand what it’s like for them to be writing away from home.

Along the way, Tu plans to continue working on her own poetry, to participate in writing workshops, and to perform at local spoken-word open-mic events. More than anything else, she hopes to find what she has always found in conversations with other women poets: a sense of community and a belief in the power of poetry as a communal act.

Between the time Tu had her final interview for the Watson in January and learned that she’d been awarded a fellowship in February, a military coup toppled the civilian government of Myanmar. Poets and other artists, traditionally aligned with the push for democratic reforms in the country, were being silenced and in some cases killed. If political developments in Myanmar mean that Tu becomes an artist in exile at the end of her Watson year, it’s likely that she will have at least found a community of kindred souls outside her homeland. “Through the Watson, I may just find that I am not alone,” she writes. “I may find that scattered throughout the world, there are individuals with whom I belong, individuals who can help me understand how best I can serve my country.”

Bramwell Atkins, “How Can We Sing? Music and Displacement”

Bramwell Atkins, C’21, is looking forward to learning to play the qeej. A traditional instrument played by the Hmong people of Asia, the qeej (pronounced ghleng) is made of bamboo and has four pipes that are used to modulate pitch. But what’s really interesting about the instrument traditionally played during Hmong funerals is that the sounds it produces are both song and language. Each note played corresponds to a word or letter so that the melody of the qeej also becomes lyrics.

The Hmong are a people without a homeland. Originally from southwest China, the Hmong have been persecuted and displaced for hundreds of years and can now be found in living in diasporic communities throughout Southeast Asia. One of the cultural elements that binds the Hmong people together, within their tight-knit communities and across national borders, is music. And that’s what Atkins will explore during his yearlong Watson project: the music specific to groups of people that arises following a major period of suffering.

The BBC visits qeej makers in Vietnam.

A lifelong musician—he was so young when he learned to play the piano that he doesn’t remember learning—Atkins says he’s long been interested in where art, especially music, comes from. “The closest I’ve come to answering that question is that the real origin of art is suffering,” he says. “And to learn more about that while traveling abroad, I thought I would look at instances of mass geopolitical suffering and the music that has come out of it.” The title of Atkins’ project, “How Can We Sing?” references Psalm 137 and the Israelites’ lamentation from captivity in Babylon: “How can we sing the songs of the Lord while in a foreign land?”

Atkins will start his Watson year in Russia, seeking out and playing with some of the top klezmer musicians in the world. Klezmer is a millenia-old folk music form of the Ashkenazi Jewish communities in central and eastern Europe that was essentially silenced during and just after the Holocaust. But in the decades following World War II, musicians in European Jewish enclaves, or shtetls, and scholars of Jewish tradition began reviving the form. Today, there’s a full-blown klezmer revival, turning the old form into a living genre that is also politically charged.

“Klezmer comes from a group of people who were at different points in time really trying to maintain a group identity and very conscious about the limits and methods of that attempt to maintain group identity,” Atkins says. “Klezmer is also very self-conscious. It’s always commenting on itself and commenting on the nature of commenting on itself.”

Atkins’ journey into the European klezmer scene will take him to Russia, Lithuania, Estonia, Poland, and Ukraine. He hopes to play with some of his favorite klezmer musicians, including top practitioners like Dan Kahn and Psoy Korolenko. He also plans to meet up with Walter Zev Feldman, one of the leading scholars of Jewish music, who also happened to inspire Atkins’ interest in klezmer when the two met during Atkins’ study-abroad semester at Oxford University.

From Eastern Europe, Atkins will travel to Southeast Asia to spend time in Hmong communities, meeting qeej players in Laos and Thailand, and following the influence of the qeej into Vietnam. There, he’ll meet and play with pioneering Vietnamese jazz musician Quyen Van Minh. Before Minh started playing jazz in Vietnam, it was illegal to do so, and the first Vietnamese jazz song was Minh’s “Song of the Qeej,” a song named not only to pay homage to an instrument whose influence could be heard in Minh’s bluesy saxophone riffs, but also to obscure the fact that the song was, in fact, jazz and not Vietnamese folk music.

Finally, after living in communities that have embraced musical traditions as a way to process mass suffering, Atkins will spend time with a group of people in the midst of suffering. He’ll finish his Watson year in Greece, where he’ll teach piano to children in Syrian refugee camps. A variety of nongovernmental organizations have worked to teach music in Greece’s refugee camps and found that the power of music can help traumatized children find joy again.

But Atkins says that just as important as knowing when to play and sing is knowing when to stay silent. In Psalm 137, the Israelites were struggling with the question of whether to make art in the face of suffering. “They said our captors asked us to sing them songs of Israel, but how can we sing in captivity?” Atkins says. “They’re saying sometimes it isn’t appropriate to make art or to speak in the face of a big question or suffering. In some ways, life is too simple and too complex for our responses. That’s something I hope to learn as well—when and when not to use words.”