A Point in Time

A determined student with a 70-year-old map and a dollar-store broom uncovers a long-lost piece of Sewanee—and Delta Tau Delta—history on a sandstone bluff.

One day in the 1880s, Archibald Butt sat on a bluff somewhere on the Domain with his Delta Tau Delta fraternity brothers and frittered away an afternoon. The guys might have told stories, joked around, and possibly bemoaned the absence of women on campus. Maybe a flask was passed around. Maybe they discussed lofty ideas or the uncertainties of their futures. What’s almost certain is that at some point, Butt used a sharp instrument to carve his last name into the sandstone, alongside the names of other Delts. All of these engravings surrounded the word “POINT” and the Greek letters “ΔTΔ” (Delta Tau Delta). Since these young men had no fraternity house, this glorious cliff, a spot they’d dubbed “Delta Point,” no doubt took on an outsized role in the life of their brotherhood.

But then they all left Sewanee, and time marched on. After joining the U.S. Army and working his way up to become an advisor to two presidents, Butt died tragically on the Titanic and became one of the University’s most illustrious alumni. More time passed. The Great Depression happened, then World War II. The interstate freeway system was built. Vietnam, the Civil Rights Movement, Woodstock, it all came and went. Sewanee began admitting women. Computers became a thing. Phones became everything. Somehow, at some point, for reasons that remain a mystery, Delts stopped going to Delta Point. Over years, then decades, the bluff became overgrown with bushes, thorns, moss, and trees. The Delts who recalled a Delta Point forgot where it was, and the Delts after them never knew it existed. Ultimately, this notable landmark on the Sewanee Domain was lost to the fog of history.

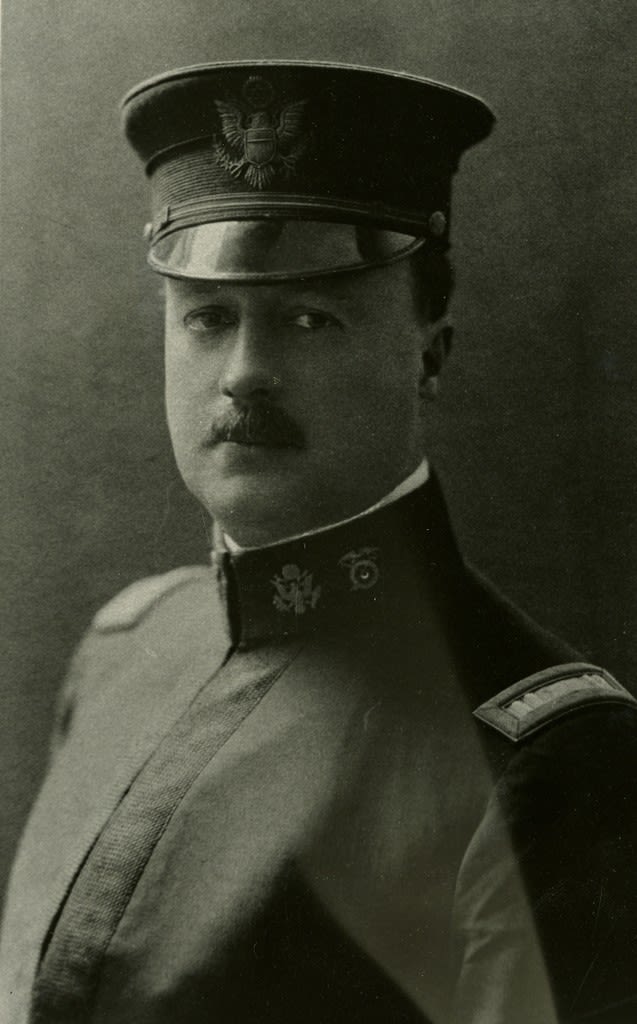

Archibald Butt, C'1888

Archibald Butt, C'1888

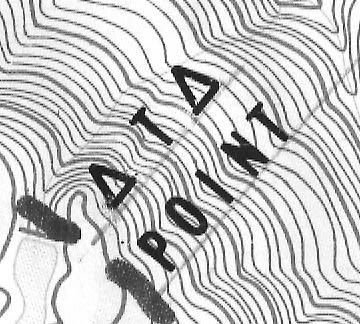

Like so many Delts before him, Mitch Shakespeare, C’24, had never heard of Delta Point when he pledged the fraternity his freshman year in the spring of 2021. The young man from Arlington, Virginia, became an environment and sustainability major, and the summer after his first year he landed an internship with Sewanee’s Office of Domain Management and was charged with maintaining trails and marking property boundaries. That latter, grueling task involved trekking into the wilderness with property deeds and old maps and refreshing the borders of Sewanee’s 13,000-acre campus by splotching paint onto trees. One day, while studying a 1950s-era map with his boss, Domain Manager Nate Wilson, Shakespeare noticed something he’d never seen on other Domain maps— “ΔTΔ POINT.” The label didn’t seem to indicate a very specific location on the relatively crude map. At best, it suggested a general area where a fraternity point might be.

This intrigued Shakespeare, a self-described history geek. Like most everyone at Sewanee, he was familiar with a couple of fraternity points on bluffs accessible by the Perimeter Trail, specifically Kappa Alpha Point and Alpha Tau Omega Point. But he’d never heard of a Delta Point. He mentioned this to his Delt brothers, but none of them knew what he was talking about. Neither did the chapter’s alumni advisor, John Baar, C'75 . If anyone might have a clue, Shakespeare figured, it would be Owen LeGrone, a Delt who graduated in 2018 and who blogged prolifically about esoteric elements of Sewanee history. In response to a query from Shakespeare, LeGrone responded with the one shred of information he was able to dig up, an article written by Ralph M. Wray in 1927 in a fraternity newsletter. “I know of nothing more inspiring than being on Delta Point, one of the cliffs, watching a sunset,” Wray wrote. “This point is famous in the chapter history.” The article explained further that “Delta Point” is carved into the rock, along with the names of chapter founders and other Delts. Wray noted specifically that “the most famous is that of Archie Butt, whose heroic death was one of the most dramatic incidents of the Titanic disaster.”

Shakespeare couldn’t resist this quest that had seemingly fallen into his lap. “All I had was a relative point on a map and this quote,” he says. “There were a lot of questions. But I became so interested and so invested. I told myself, ‘I’m going to find it.’”

With the blessing of Wilson and Domain Management, and armed with nothing more than his phone GPS and a broom and dust pan from Dollar General, Shakespeare set out one Saturday morning and began wrestling his way through bluff-top thorn bushes. The spots he went to were so overgrown that he couldn’t even see rock. “It was trial by fire,” he says. “I was wearing shorts. I got all slashed up. After three hours, I found zero and went home. It was disheartening.” But at work the following week, all he could think about was finding Delta Point. The idea intoxicated him.

The next Saturday he tried again. This time he wore long pants. Unlike his previous outing, he started at the base of the bluffs and looked up for promising sites. He spent all day scrambling up and down, dodging copperheads and coyotes. “I tend to risk my well-being to achieve a goal,” he says. “It’s not the greatest thing. But I get swept up in this all-or-nothing mindset.” At one promising bluff he discovered a single name carved into the rock. He got super excited. After a strenuous hour of digging, some Greek letters emerged—but they weren’t “ΔTΔ.” Yes, he had found a long-lost fraternity point, just not the right one. For about five minutes he was completely bummed out. Then he thought, “O.K., I just discovered something important. At the end of all this I’ll have two points, not just one.” The discovery of the other point also verified a theory of his. If the KAs and ATOs had points, wouldn’t all of the early fraternities have had points? With no cars, TVs, or computers, students in the 1880s were probably thrilled to while away time on the Domain’s gorgeous bluff tops.

On Shakespeare’s third Saturday out, he approached a bluff with a suspicious-looking mound atop it, about two-and-a-half feet high and six feet across. It was as though someone had piled a load of dirt there 60 years ago, and nature had since covered it over with grass, moss, and a few small trees. Shakespeare was probing along the edge of the dirt when he saw it — a small “ΔTΔ” carved into the rock. “Holy shit!” he yelped. “This has to be it!” With no shovel or trowel, he found a sharp, flat rock and attacked the mound like a man possessed. Over four hours of digging, he found name after name, and then, right before sunset, he discovered the large, telltale “POINT ΔTΔ” carving. He would find Butt’s name on the rock a week later, on his fourth outing. “That was the moment for me,” he says. “Fraternity brothers aren’t just the guys in your current brotherhood, but also those who came before. To be able to call people like Archie Butt brother is an amazing thing. To see him chiseling into that rock, surrounded by brothers, I almost wept.”

Inscriptions on Delta Point, including (above), one believed to have been carved by Archibald Butt. Photos by Mitch Shakespeare

Inscriptions on Delta Point, including (above), one believed to have been carved by Archibald Butt. Photos by Mitch Shakespeare

Shakespeare reported the 13 names he found on the bluff to LeGrone, and together they dug into archival materials to determine who these guys were. Two of them, Norman Bond Harris and Rowland Hale, helped found Sewanee’s Beta Theta chapter of the Delts in 1883. Others were members who came later, and three weren’t Delts at all but young men who attended the Sewanee Grammar School. Butt wasn’t an original founder, but he joined the same year the chapter was born, becoming its ninth member. Shakespeare can’t know for certain that the Butt etching belongs to Archie and not his younger brother Lewis, who attended Sewanee for three years and left without a degree. But it is Archie who Wray mentions in the 1927 article. “Someone was with Butt when he carved it and passed down that story,” Shakespeare theorizes. “With Butt’s career and dramatic death, that’s a story that would have continued to be passed down, and that’s how Wray would have known. I feel 80 percent sure Wray is correct.”

Nate Wilson and Domain Management, with input from University Archaeologist Sarah Sherwood and Shakespeare, have decided to keep the location of Delta Point secret for now, for several reasons. For starters, the spot remains basically an incomplete archaeological site, with likely more names to discover. Secondly, such work would need to be done carefully to avoid disturbing the bluff's sensitive ecology and potential archaeological sites below. And finally, no one wants to see Delta Point vandalized, as has happened at KA Point, with people etching over 140-year-old names. Shakespeare says the plan is to devise a way to protect the site and then share it with the community. Until then, he’s limiting sightseers to Delts past and present. “It’s on a need-to-know basis,” he says. “If a member of the fraternity, an alum, wants to see it, then yes, it’s part of their history.”

The project has driven Shakespeare to take on another Delt-related historical quest. He’s attempting to tell the story of every member of Beta Theta chapter past and present. So far he has researched and written up 800 names. “Many of these guys were lost to history, just like Delta Point,” he says. “There’s a rich history behind every name, and it’s waiting to be discovered.”